Opera

Britten from scratch

Louis Jebb

Two years ago many people found it unbearable to be in the same room as me while I was singing, so loud and coarse was the noise, and I took to having lessons. After six months the noise was sweeter but shyness drove me to sing to people from an adjoining room. Another six months on, the will to perform in public developed. By last August I had my first commission ŌĆö a Faure song at a wedding in Wales ŌĆö and last Sunday appeared in Peter Grimes at the Royal Opera.

This rapid and romantic progress to the singers' Mecca is entirely down to my singing teacher, Emma Petre. But I should point out ŌĆö not wishing to appear like the woman who declared herself 'connected to royalty' because her sister had once shaken hands with Princess Christian of Schleswig- Holstein ŌĆö that a few people still wish I would sing in another room, and that I appeared at Covent Garden without an audition; before an audience of 80 people; in the opera rehearsal room and not on stage; at my suggestion not theirs; paying rather than being paid, and not as a soloist (although my black gumboots took a prin- cipal part, on the feet of the Balstrode, John Handcorn) but in the chorus, a chorus which included at least two people ŌĆö a retired naval officer and an au pair from Barcelona ŌĆö who had never sung a note in their lives.

We were part of a Practical Opera Weekend organised by Covent Garden's education department. For ┬Ż35 anyone could take part in the production, choosing to sing, to make sets or costumes or to light or manage the stage. A series of scenes from Britten's opera had to be prepared in every respect from scratch between six p.m. on Friday and four p.m. on Sunday afternoon. Enthusiasm seems guaranteed on these occasions but live tension was generated by this impossible deadline.

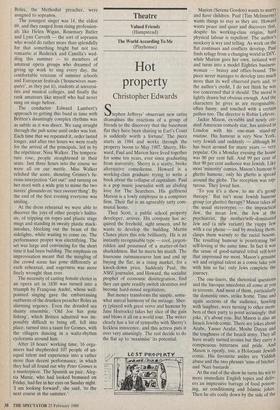

As a chorus of fishermen and townspeo- ple we had to prepare the pub scene in detail and the succeeding beach scene to be sung with scores in hand. The first problem was one of sexual balance. It is a truism of amateur music that always more women than men apply. In this case we had 21 sopranos, 15 mezzo-sopranos, 11 basses and one tenor. So few men had asked to be soloists that the parts of the rector and Boles, the Methodist preacher, were assigned to sopranos.

The youngest singer was 14, the eldest 69, and they ranged from rising profession- als like Helen Wigan, Rosemary Butler and Lynn Carveth ŌĆö the sort of sopranos who would do rather more than splendidly for that something bright but not too romantic at Roderick and Camilla's wed- ding this summer ŌĆö to members of amateur opera groups who dreamed of giving up work to sing every day, the comfortable veterans of summer schools and European festivals (`housewives man- quies% as they put it), students at universi- ties and musical colleges, and finally the rank amateurs like myself who had never sung on stage before.

The conductor Edward Lambert's approach to getting this band in time with Britten's dauntingly complex rhythms was as subtle as it was direct. We sang straight through the pub scene until order was lost. Each time that we repeated it, order lasted longer, and after two hours we were ready for the arrival of the principals, led in by the repdtiteur, Nina Walker. The tempera- ture rose, people straightened in their seats. Just three hours into the course we were all on our mettle. Miss Walker relished the score, shouting Grimes's fu- rious interjection 'Get out!' and turning on her stool with a wide grin to mime the two nieces' glissando on 'nice sweeeet thing'. By the end of the first evening everyone was smiling.

At the dress rehearsal we were able to discover the joys of other people's halito- sis, of tripping on ropes and plastic stage mugs and standing in sweaty plastic mack- intoshes, blocking out the beam of the sidelights, while waiting to come on. The performance proper was electrifying. The set was large and convincing for the short time it had been building. The emphasis on improvisation meant that the mingling of the crowd scene has gone differently at each rehearsal, and eagerness was more finely wrought than ever.

The necessity of casting female clerics in an opera set in 1830 was turned into a triumph by Francoise Andre, whose well- pointed singing gave the embarrassing outbursts of the drunken preacher Boles an alarming urgency. Even the dreaded sea shanty ensemble, 'Old Joe has gone fishing', which Britten admitted was im- possibly difficult to bring off, fell into place, turned into a taunt for Grimes, with the villagers dancing in a waltz-rhythm cyclorama around him.

After 18 hours' working time, 16 orga- nisers had shepherded 107 people of un- equal talent and experience into a rather more than decent performance, in which they had all found out why Peter Grimes is a masterpiece. The Spanish au pair, Aleg- ria Muniz, who had looked bemused on Friday, had fire in her eyes on Sunday night. 'I am looking forward', she said, 'to the next course in the summer.'

Previous page

Previous page