A CONSUMER'S GUIDE TO CRITICS

The flay's the thing

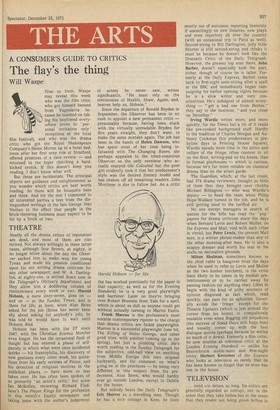

Will Waspe

True to form. Waspe may reveal this week who was the film critic who got himself banned from Yugoslavia because he insisted on taking his boyfriend everywhere (even to personal invitation only' receptions at the local film festival), and who was the drama critic who got the Royal Shakespeare Company's Helen Mirren up to a hotel bedroom after her first sexy role at Stratford, offered promises of a rave review — and returned to the foyer clutching a hardkicked crotch. If this doesn't keep you reading, I don't know what will. But these are incidentals. The principal objects are guidance and enlightenment as you wonder which critics are best worth reading. So there will be bouquets here and there. And for the rest I commend to all interested parties a text from the distinguished writings of the late George Jean Nathan to the effect that people in. the brick-throwing business must expect to be hit by a brick or two.

THEATRE

Nearly all the drama critics of reputation are dead, and most of them are also retired. Not always willingly in these latter

cases, although Ivor Brown, at eighty, is no longer bitter about the day the Obser ver sacked him to make way for young

Tynan and made his pension conditional upon his not writing drama criticism for any other newspaper; and W. A. Darling

ton, at eighty-one, is settled down now in the Telegraph's Obituary department and they allow him a doddering column of reminiscence every week or two. Harold Hobson, a mere sixty-seven, goes on — and on — at the Sunday Times, and is there for life; at least, when Alan Brien asked for the job (Brien has never been shy about asking for anybody's job), he was told he would have to wait until Hobson died.

Hobson has been with the ST since 1947, with the Christian Science Monitor even longer. He has the occasional flash of insight but has entered a phase of selfparody in which what were once incidental quirks — his francophilia, his discovery of new geniuses every other week, his quotations from his early reviews of Pinter, and his detection of religious motives in the unlikliest places — have more or less taken over. He has often been spoken of as primarily 'an actor's critic,' but actor Ian McKellen, reviewing Richard Findlater's The Player Kings for the profession in this month's Equity newspaper and taking issue with the author's judgement

of actors he never saw, writes significantly, "He must rely on the testimonies of Hazlitt, Shaw, Agate, and, heaven help us, Hobson."

Since the departure of Ronald Bryden in September, the Observer has been in no rush to appoint a new permanent critic — presumably because, having been stuck with the virtually unreadable Bryden for five years straight, they don't want to make the same mistake again. The job has been in the hands of Helen Dawson, who has spent most of her time being infatuated with The Changing Room; she perhaps appealed to the trend-conscious Observer as the only reveiwer who actually enjoyed Oh! Calcutta! but the poor girl evidently took it that her predecessor's style was the desired literary model and has shaken off all remaining readers. John Mortimer is due to follow her. As a critic (he has worked previously for the paper in that capacity, as well as for the Evening Standard) he is a very good playwright and barrister. Later on they're bringing over Robert Brustein from Yale for a spell, which is about as dull as anyone could get without actually turning to Martin Esslin. Frank Marcus is the profession's most notable contemporary riposte to the charge that drama critics are failed playwrights. Marcus is a successful playwright (one hit, The Killing of Sister George, and other good tries, with another coming up in the spring), but just a plodding critic. He's worth reading in the Sunday Telegraph for the subjective, odd-ball view on anything from Middle Europe (his own original backyard), and for comment on what's going on in the provinces — he being very different in this respect from his predecessor, Alan Brien, who would hardly ever go outside London, except to Dublin for the booze.

But nobody beats the Daily Telegraph's Eric Shorter as a travelling man. Though he has a nice cottage in Kent, he lives mostly out of suitcases, reporting literately if unexcitingly on new theatres, new plays and even repertory all over the country (with an occasional trip to Paris as well). Second-string to Bill Darlington, jolly little Shorter is still second-string and thinks it must be because he doesn't look like the Dramatic Critic of the Daily Telegraph. However, the present top man there, John Barber, doesn't especially look the part, either, though of course he is taller. Formerly at the Daily Express, Barber came back to first-night aisle-sitting after a spell at the BBC and immediately began campaigning for earlier opening nights because he is a slow writer and very conscientious. He's indulgent of almost everything — "get a bad one from Barber," they say in the business, "and you close on Saturday."

Irving Wardle writes more, and more quickly, for the Times but a lot of it reads like pre-cooked background stuff. Hardly in the tradition of Charles Morgan and Anthony Cookman (his predecessors in prebyline days in Printing House Square),

Wardle spends more time in the attics and cellars of the fringe, often content to sit on the floor, writing-pad on his knees, than in formal playhouses — which is curious, because he's far more reliable on classical drama than on the avant garde.

The Guardian, which, at the last count, had 374 drama reviewers, thought so little of them that they brought over chubby Michael Billington — who was Wardle's deputy — to head the team when Philip Hope-Wallace turned in the job, and he is still getting used to the rarified air.

No one except managers in search of quotes for the bills has read the 'pop ' papers for drama criticism since the days when Bernard Levin and Robert Muller, on the Express and Mail, vied with each other in vitriol, but Peter Lewis, the present Mail man, is a wittier phrase-maker than any of the other morning-after men. He is also a snappy dresser and worth his seat in the stalls on decorative grounds.

Milton Shulman, sometimes known as the chief rabbi (a hangover from the days when he used to refer to Levin and Muller as the two kosher butchers), is the critic least likely to be taken in by modish pretentiousness or to be carried away by passing fashion (or anything else). Likes to begin with the kind of pithy sentence of opinion disguised as fact which, read quickly, can pass for an aphorism. Generally avoids the ' fringe ' except for the Theatre Upstairs (which is just around the corner from his home), is compulsively readable even when flogging old prejudices (the success of Salad Days still bugs him) and usually comes up with the best dialogue quotes (perhaps because he writes so much of it down). Formerly a film critic, he now doubles as television critic at the London Evening Standard — unlike his Beaverbrook stable-mate and first-night crony, Herbert Kretzmer of the Express who looks at television so rarely that he has been known to forget that he even has one in the house.

TELEVISION

. . . need hot detain us long. Its critics are generally regarded as corrupt, not in the sense that they take bribes but in the sense that they resent not being given bribes in

sense that they resent not being given bribes in the shape of work. Most of them would rather write for than about television and are violently harsh about producers and companies who turn down their scripts. The rest are largely unknown people even at their papers, except as late-night voices on the telephone. This is a practice that leads to many misprints, especially afflicting Nancy Banks Smith, who must be a very good-humoured lady for her columns are collector's items in this respect even by Guardian (or even Spectator) standards, but she is always fun to read and is about the only critic who can be witty when praising seriously.

Alan Brien, having failed to displace Harold Hobson at the Sunday Times (see Theatre), had to settle for television and is defeating the hopes that were probably cherished that this would stop him writing about Alan Brien and plugging another journal for which he works, the name of which is right on the tip of my tongue. Similar hopes may have been behind the Observer's giving television to Mary Holland, who must have been an embarrassment as a political and social reporter; but she continues to write mainly about the same things and is still an embarrassment.

Apart from Miss Smith, the only newspaper reviewers worth reading are Cuthbert Worsley who is very serious and shrewdly analytical at the Financial Times (where he was formerly drama critic, but gave it up because of ill-health); Barry Norman, who does occasional, amusing pieces for the Times; and Milton Shulman (see also Theatre) whose Evening Standard column is mysteriously called 'Inside TV' (which it hasn't been since its early days when it was mostly a reprisal for his exit from Rediffusion). Shulman, because of his theatre job, and probably from inclination as well, doesn't watch anything regularly except Saturday-afternoon racing, but sees enough to come up weekly with a set of provocative generalisations that have them going spare in the backrooms inside TV.

If anyone ever starts a Men's Lib movement, film criticism would be a good area of operations. The stranglehold of the ladies has lately been loosened slightly (at least, to the extent that not every girl called Penelope can be guaranteed a job in the trade), but the change is barely perceptible either in print or at the press show ings. Only the other day someone was saying that the most virile film critic was Penelope Houston, the editor of Sight and Sound.

The elder stateswoman is Dilys Powell of the Sunday Times who has been around since films were invented and sometimes reads that way. Despite her great age, though, she strives to maintain a modern look while regretting that things are not as they were. Dilys is the Jennifer of the film wcrld, as opposed to George Melly who is the Germaine.

Melly, who writes for the Observer, is also a sturdy supporter of Alexander Walker of the Evening Standard in his efforts to control how films are advertised, although all the two have otherwise in common is that both have been elected to the title, Critic of the Year.' Melly got his for writing about television, and those who read him on films and know about the accolade feel he must have dropped off since then; that is, if they have not themselves dropped. off, for he has soporific ways with prose, even when writing about sex — which is usually.

Walker, the well-known letter-writer, is a Northern Irishman and thus not a little pugnacious. He is knowledgeable about Kubrick and has just completed a book to prove it. Unmarried except to his job, and sometimes gives the impression of caring about films, which may be his undoing.

John Russell Taylor, who can startle even his colleagues by bringing monogrammed hankies to weepie pictures, got a double first at Cambridge and immediately wrote a book on art nouveau and another on theatre and became film critic of the Times where he writes so flowerily as to be almost in bloom. Seems very much to want to be everybody's critic and will probably never get up from between the stools of the commercial epics and the artily esoteric.

Anybody who wants really learned criticism reads John Weig,htman, who is Professor of French at Westfield College and writes for Encounter with unmalicious wit.

Unfortunately, the ones most are familiar with are on television. Film Night on BBC TV is a joke, presided over by a patronising bunch of toadies who would hardly have got employment as stand-ins for Fatty Arbuckle. TV producers, always on the lookout for a cheap thirty minutes, do as the big film distributors tell them. All they have to do, they are told, is to get in as bland a front man as possible, don't criticise and don't mention art, and we'll keep on giving you lunch at the Savoy. Think I'm joking? No wonder we get the cinema we deserve.

MUSIC

There is probably more social intercourse (to put it no higher) between writers and written-about in the world of music than in any of the other arts. It is perhaps too much to suggest that all interests be declared and that every notice should begin somewhat thus: "Mr A is a pianist/soprano/conductor of genius, but integrity demands that I mention that I have known him from boyhood and in fact slept with his wife only last Thursday lunchtime while he was rehearsing at the Queen

Elizabeth Hall" — but it would be refreshing if it happened just once in a while, and any music critic who does it will instantly become my favourite. If I omit your own favourite from the following rundown, it is because the breed is very thick on the ground — with concerts, recitals, opera and records to be covered they come three or four to a paper.

Philip Hope-Wallace is the acknowledged doyen and has now virtually abandoned the theatre in favour of the opera house. He has vast personal experience,

and total recall of unique performances of forgotten French operas in forgotten French provincial towns fifty years back — a useful attribute for a Guardian critic of the 'seventies. Unquestionably good on the dramatic side of opera, but his loftily Georgian style accentuates his remoteness from contemporary, everyday life. A Balliol man, though, and much respected.

Edward Greenfield one of his ,Guardian colleagues, has been known to sport a discreet earring, but is otherwise unremarkable save for a similarly disconcerting habit of quoting loudly from his own reviews at press functions and a tendency to over-praise those with whom he dines.

Desmond Shawe-Taylor, by appointment elitist critic to the privileged, writes in the Sunday Times. Only knowledgeable sophisticates and degree-holders need even begin to read him, and it is unlikely that anyone has reached the end of one of his notices for a decade. He believes opera should stay in the nineteenth century where it belongs and is, appropriately enough, a keen croquet player.

Martin Cooper, known by some as "The Colonel" because of an upright military bearing unique among critics, is also almost unique in having once actually studied music. At sixty-one, he is marginally older than Hope-Wallace and ShaweTaylor, but is tdo down-to-earth to assume the mantle of doyen. Daily Telegraph to the core.

William Mann, despite his forty-seven years, is one of the swingers and hasn't worn a tie since the Coronation (of Poppea); his startling paean to the Beatles in the Timer seems, in retrospect, almost predictable. But for occasional lapses into pettiness. Mann would be at the top of his trade, for he is knowledgeable, humane, eminently readable and always read. A frustrated organist, known to doze a little.

His colleague, Alan Blyth, industrious and affable, writes everywhere, is every Where, still manages to say virtually nothing. But everyone likes him and his wife is very decorative.

More music critics read Andrew Porter of the Financial Times than any other (and some, they say, file his reviews for use at a later date). A frustrated pianist, he combines formidable knowledge with readability, enthusiasm and, except at Covent Garden, ruthlessness (see also Ballet).

Gillian Widdicombe, his colleague at the FT, is certainly the prettiest critic in town, not even forgetting Richard Buckle. All the musical world takes turns to languish at her beautiful feet (only the rich or powerful need aspire to anything higher). Her instrument is the organ, and she has graduated from the baroque to specialise In everything. Still in her twenties, she is Most Likely to Succeed Almost Anyone.

ART

It is entirely possible that no one except gallery owners, artists and other art critics reads art critics. (Have I got you, I wonder, before you begin skipping?) They incite little challenging correspondence. However startling their views, their words wear a cloak of academic immunity that discourages the innocent.

John Russell casts the spell most persuasively of all and is the one to whose favour all galleries and artists aspire. He has been writing for the Sunday Times for over twenty years (also for some of the best US art magazines), and is a very big gun (also, in some ways, hardly more than a pea-shooter). Russell writes weighty, authoritative books (Seurat, Henry •Moore, Ben Nicolson etc) but as a reviewer often seems more concerned with giving himself a trendy 'seventies image: he never misses anything at the Angela Flowers Gallery, and gives his approving nods to Gilbert and what's-his-name in everything they do. (Will the real John Russell please stand Up?) Contrary to popular belief, it is possible to distinguish Nigel Gosling (see also Ballet) from John Russell. Gosling writes for the Observer. If challenged to distinguish one from t'other, look out for the Phrases designed to assure the students that he's read a book or two and knows the difference between linseed oil and turps subs. It's true that he's also fond of George and what's-his-name and gets to Angela's place fairly regularly. But he has his own way of wriggling out of problems Posed by avant-garde Work: the question of whether he likes it or not becomes a mystical exercise. Is it good? "But who is to say?" is Gosling's likeliest answer — er, question.

Terence Mullaly, fair, sincere, predictable, is the Daily Telegraph's man and Is far less likely (indeed not likely at all) to be caught flirting with talents that don't Meet the Establishment criteria. He reserves all his enthusiasms for the past (he was formerly an archaeologist) and long ago committed his heart to sixteenthand seventeenth-century Italian art. It is unsurprising to know that he comes from a family bristling with military men; somehow astounding to know that he is only forty-four.

The Guardian's readers probably have their own image of Caroline Tisdall, and I'm afraid I'll have to disillusion them. She's not unattractively squat, flat-heeled and tweedy; but, on the contrary, rather dishy. That she writes pieces that seem to be asking for a tutor's approval may be partly because she v.ants her students' approval (she lectures at Reading), and partly because she has her own image of a liberal Hampstead audience who like to know about dates and things. Even when she does break out and say something quite nasty, she does it very, very seriously.

Guy Brett projects an image, too, and the Times has space to burn for him to do it. Tossing the jargon about in great gobbets, he reads like the stereotypical art critic of Hollywood movies in the 'thirties (silver-knobbed cane, cape and all), and it is somehow refreshing in this cynical age to read the kind of clichés that must make strong artists weep. In fact, Brett is a fair-haired, ascetic young man. Son of Lord Esher, the town planner, he is almost painfully sincere, dedicated wholly to his subject (he is said to have no interest in books or any other of the arts), and clearly has no idea why he appears so often in Pseuds' Corner.

Posing as an art critic in the London Evening Standard, but really just an enter

prising journalist who found himself with the assignment, Richard Cork is looking for a reputation as a trendy and does his best to popularise the bizarre. Gilbert and what's-his-name reached their lunatic apotheosis the other week in two pages from him — in colour, too, which gave Cork the rare guarantee that his stuff would stay the course to the late editions.

A kindly word for Michael Shepherd of the Sunday Telegraph, an espouser of artists' causes. He writes consistently with more depth and intelligence than the rest, has a keen sense of responsibility towards the artist and mentions as many as he discriminatingly can. Trouble is, only artists read him, which is where we came in.

BALLET

Since ballet is more likely than the other arts to attract maniacal enthusiasts, so single-minded that they probably don't even read newspapers, it follows almost naturally that the doyen of ballet critics doesn't write for a newspaper and is not himself interested in anything in the world except ballet. The name is Peter Williams. He has been editing Dance and Dancers for twenty-one years (got an OBE for it), comes from the Cornish tin mines and looks like an ageing roue. Williams's knowledge in his special field is encyclopaedic and he is not given to the prejudices of his opposite number at Dancing Times, a nice, intelligent girl called Mary Clark who also owns her magazine. Miss Clark recently ground some of her axes before a slightly wider public when brutally condemning the Cullberg Ballet in the columns of the Guardian.

The Guardian's regular ballet critic would now seem to be Philip Hope-Wallace (see also Music), who has replaced James Kennedy — who was only a part-time ballet man but kept marrying ballerinas (including Merle Park, the second of his wives but never plugged and rarely mentioned in his reviews). Kennedy is better known as James Monahan, who was controller of the BBC's European Service (and a contender for Charles Curran's job) and is now working in German radio.

Being a ballet critic is also a part-time thing with John Percival who is a GLC bureaucrat at County Hall as well as the Times pundit. He has a nervous tick, loathes folk-dance groups, looks for narrative clarity in the classics, and has a bad reputation at the Royal Opera House where Lord Drogheda and Kenneth Mac ballet nights are collared by Andrew Porter (see also Music), who not only works directly for Lord Drogheda (boss of the FT, as well as chairman of the Opera House) but is also the brother of Covent Garden's much-put-upon press officer, Sheila Porter. Some people think this combination of circumstances cannot be wholly unconnected with the fact that, while all the other critics panned MacMillan's recent Anastasia fairly vigorously, Porter praised it ecstatically.

Willowy Clement Crisp, who used to write in these pages, and might have been drawn by Anton, is officially the FT's ballet critic and combines superior technical knowledge with a needling wit. Also a part-timer, he teaches French at Dulwich.

Fernau Hall's other job is with Thames TV. A grey suede character in a grey suede jacket, he succeeded the late A. V. Coton at the Daily Telegraph; used to be a dancer, knows quite a lot about Indian dancing, and gives quite a show of erudition about all other exotic ethnic groups — though the other critics think he makes half of it up. Noel Goodwin, who has an expensive hairstyle and a beautiful wife and whose heart is in the right place (i.e. the twentieth century), would have liked the job and might have made something more of it, but is stuck instead with the Daily Express where even Clive Barnes didn't get much of a show. Over at the Daily Mail ballet has been entrusted to David Gq1ard who can be said to know more about ballet than anyone else in the Daily Mail.

The ' posh ' Sundays don't rate highly in this field, although Richard Buckle of the Sunday Times, despite his flamboyance and self-indulgence, is well-loved in the profession and has lately written a good biography of Nijinsky. As an exhibition and gala organiser, he is a sort of Midas in reverse. Alexander Bland, ballet critic of the Observer, is Nigel Gosling, art critic of the Observer — or possibly Mrs Gosling, formerly of the Ballet Rambert.

Annabel Farjeon who graces the London Evening Standard is a doctor's wife who got booted out of the Royal's corps de ballet by Ninette de Valois. It was no use her trying to get her own back in print, for Dame Ninette doesn't bother with reviewers, and nowadays Annabel is polite and pointless — if not quite as kind as Jimmy Kelsey of the Evening News, who has friendly words for all and is especially nice to the Festival Ballet.

FINALLY . . .

The reviewers you come across regularly in these columns are all bigger than me, and I should like to say that Kenneth Hurren (theatre), Tony Palmer (cinema), Hugh Macpherson (opera), Robin Young (ballet), Rodney Milnes (music), Evan Anthony (art) and Duncan Fallowell (pop) are all splendid fellows, as knowledgeable as they are well-graced. All, that is, except one.

As for those two threatened revelations, well, the spirit of Christmas has overcome me. But you could ask the Yugoslav Embassy about one; and Miss Mirren about the other, about which all I shall say, for everyone's peace of mind, is that it most certainly was not Harold Hobson.

Previous page

Previous page