Indian art

Tender sage

Juliet Reynolds

0 f all India's numerous museums, one of the richest in masterpieces is located in the provincial city of Mathura which stands on the banks of the Jamuna not far upriver from the Taj Mahal at Agra. But while Agra is best known for its association with the Mughal dynasty, Mathura's renown lies far back in antiquity. During the Buddha's lifetime it was the seat of a tribal republic

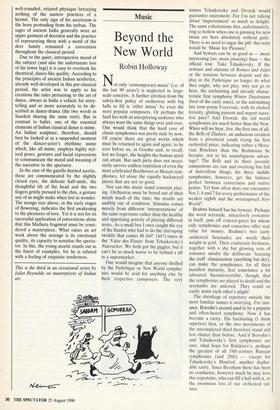

'Rishyashring', sandstone, c. 2nd century, at the Mathura Museum

growing rich and powerful from agriculture and river trade. In subsequent centuries, as Buddhism and trade expanded side by side across the subcontinent, Mathura became a flourishing religious and mercantile cen- tre, the result of its strategic position along the north-south and east-west trade routes. During the second century BC it also became settled by dissident monastics, expelled from the Order for their deviation from the Buddha's principles, both philo- sophical and practical. Some of these dissidents were later to settle at Taxila, capitll of the fabulously rich Gandhara province formerly ruled by the Persians and Alexander, for long a haven for unorthodox thinkers. Mathura and Taxila maintained strong links for many centuries and were the first Buddhist centres to abolish the taboo on representations of the Buddha around the first century AD. The Mathura style, however, differs greatly from that of the Graeco-Buddhist Gan- dhara school, its artistic sources being almost entirely indigenous. The imagery developed here is distinctly its own though it bears much resemblance in form and content to that of other Buddhist sites across the Indian heartland.

Yet by no means all the art patrons of Mathura were Buddhist. From the first to the fifth centuries, when its workshops flourished, numerous commissions were received from Jains, adherents of a non- violent philosophy similar to Buddhism and, like it, greatly supported by traders, as well from the devotees of various Hindu deities and cult figures. A large number of sculptural remains from Mathura lie scat- tered in collections across India and abroad. But the exhibition and store- rooms of its museum remain stuffed to capacity, its masterpieces squashed be- tween works of lesser merit and so often lost to all but the initiated eye.

One of the most delightful of these great works is indeed Buddhist. This is the figure of a young man who once belonged to the railing surrounding a stupa (Buddhist ceno- taph). Created between the second and third centuries, this red sandstone sculp- ture is a representation of Rishyashring (meaning gazelle-horned), an ascetic appearing in the Jataka, a compilation of stories which relate events in the past

incarnations of the Buddha and which were the principal theme of Buddhist narrative art. According to the episode identified with the Mathura fragment, the still adolescent Rishyashring lives in a hermit- age and is entirely ignorant of the existence of women. But one day he is visited by a young beauty who, taking advantage of his innocence, seduces him. The sculpture represents him in the moments of deep wonder following his surprise introduction to sensual pleasure.

Exemplifying the spirit of early Buddhist art with its emphasis on well-being and joy, Rishyashring is carved with all the grace and elegance of a young aristocrat, his well-rounded, relaxed physique betraying nothing of the austere practices of a hermit. The only sign of his asceticism is the horn protruding from his turban. The sages of ancient India generally wore an upper garment of deerskin and the practice of representing them with a • motif of the deer family remained a convention throughout the classical period.

Due to the quiet, introspective mood of the subject (and also the unfortunate loss of his lower legs) it is easy to overlook his theatrical, dance-like quality. According to the principles of ancient Indian aesthetics, already well-developed in this pre-classical period, the artist was to apply to his creations the rules pertaining to the art of dance, always in India a vehicle for story- telling and so more accurately to be de- scribed as dance-drama (the two words in Sanskrit sharing the same root). But in contrast to ballet, one of the essential elements of Indian classical dance is mime.

An Indian sculpture, therefore, should best be looked at as a suspended moment of the dancer-actor's rhythmic mime which, like all mime, employs highly styl- ised poses, gestures and facial expressions to communicate the mood and meaning of the narrative to the spectator.

In the case of the gazelle-horned ascetic, these are communicated by the slightly closed eyes, the delicate half-smile, the thoughtful tilt of the head and the two fingers gently pressed to the chin, a gesture any of us might make when lost in wonder.

The mango tree above, in the early stages of flowering, indicates the first awakening to the pleasures of love. Yet it is not for its successful application of conventions alone that this Mathura fragment must be consi- dered a masterpiece. What raises an art work above the average is its emotional quality, its capacity to sensitise the specta- tor. In this, the young ascetic stands out as the finest of examples, for he is infused with a feeling of exquisite tenderness.

This is the third in an occasional series by Juliet Reynolds on masterpieces of Indian art.

Previous page

Previous page