Belated Brownie points

Francis King

BOY During my three-year Presidency of the international writers' organisation PEN, I encountered a strange phe- nomenon whenever a writer was impris- oned or a book was banned. This was that, in registering their protests, the majority of PEN members would at once exaggerate the literary distinction of the writer or the book in question. I eventually came to the conclusion that such people believed that the persecution of first-rate writers was morally more reprehensible than the persecution of mediocre ones.

Curiously, the persecutors seemed to take the same view. When, for example, as one of the British delegates at a CSE cultural forum in Budapest, I spoke out against the imprisonment of the poet Irina Ratushinskaya, one of the Soviet delegates came up to me afterwards to say in sweetly reasonable tones: 'Mr King, why do you concern yourself with this woman? If you could read Russian, you would realise that she is a bad writer.' To that I replied that, if in England we took badness as a reason for imprisoning writers, we should have to build new gaols in order to accommodate them all.

When a book has been banned in this country, the protesters against the banning have similarly exaggerated its worth. Pri- vately, E. M. Forster did not think all that much of Lady Chatterley's Lover, but in court he testified, along with other writers of distinction, to its 'very high literary merit'. Although Forster himself did not claim very high merit for The Well of Loneliness, thus upsetting its author Rad- cliffe Hall, others did so at the time of its prosecution and have done so ever since. Similarly, James Hanley's Boy, now re- issued in its first unexpurgated edition since its publishers were fined for pub- lishing an obscene libel in 1934, has more than once been described as a work of genius. In fact, for all its undeniable qualities, it is nothing of the kind. Written in ten days on a typewriter bought for the impoverished author by Nancy Cunard, it is altogether too monotonous in tone, too monochrome in style and too slipshod in plotting for that. Hanley himself, a man as scrupulously honest about himself as about the world around him, confessed many years later that he found the book 'shape- less and crude and overburdened with feelings.'

Like his protagonist Fearon, Hanley himself ran away to sea from a working- class home in Liverpool at the age of 13. One guesses, therefore, that, in writing his novel, he was in effect saying to all those people whose knowledge of seafaring life was derived from the writings of Joseph Conrad and H. M. Tomlinson: 'So that's your romantic view of how sailors behave, think and talk, is it? Well, this is what I found.' Fearon's terrible experiences were not Hanley's own, as he more than once pointed out; but he had seen at first hand the kind of brutality, the product of ignor- ance and deprivation, which lead to them.

We first meet Fearon as a schoolboy, the only child of parents living in poverty of a kind then common but now rare in western Europe. He has dreams of remaining at school, in order eventually to become a chemist. But, needed as another family wage-earner, he is propelled into a job, filthy and ill-paid, down at the docks. To escape both this job and the violence of his father, he stows away on a ship, only to find that life is even more hellish at sea than on shore. Almost without exception, the seamen on the ship, married or unmar- ried, wish to use him as 'a Brownie'; and when he repulses their advances, they bully him with unflagging malevolence. He is constantly at everyone's beck and call; and any failure in a task is punished with a cuff or a kick. When the ship arrives in Alexan- dria, he loses his virginity to a prostitute in a scene which Richard Aldington, with some exaggeration, described as 'done with a poetic sensuality achieved by no- body since Lawrence.' Syphilis and murder at the hands of the disgusted, drunken captain follow.

The first defect of the book is that, almost without exception, all the men on the ship are crude, cruel and depraved. Since Fearon is such a decent, hard- working and appealing character, it is hard to believe that so few people would be prepared to look after him or stand up for him. The second defect is Hanley's all too obvious ignorance about the syphilis which provides the horrific denouement of the novel. Two days after sleeping with the prostitute, Fearon has begun to feel des- perately ill; and within a week he has already reached the secondary stage of the disease, with a rash (accompanied, in his case by a typical itching of such acuteness that it drives him to a frenzy) and ulcers. The third and most important defect is the stilted weirdness of so much of the dia- logue. Did a working-class Liverpool mother ever chide her son: 'You brazen cur!' or 'You excitable pig!'? Did one seaman ever curse another: 'Stiffen the sod dead!', 'You hard-faced whelp!' or 'You double-faced bastard of a Turk!'?

Nonetheless, for all its defects, this remains a work of remarkable power. There is greatness in the depiction of the physical squalor of the ship and its men; in the handling of the boy's loss of his virginity in the brothel; and, above all, in the description of how the huge, shaggy captain, after several days of hard drinking

in his cabin, 'placed the great-coat over the face of Fearon, and laid all his weight upon it', thus putting the boy out of his misery as though he were a mortally ill puppy or kitten.

Anthony Burgess has provided an intro- duction. He thinks that Hanley, a writer of 'rare merit and scant readership', should have received the Nobel Prize; and he detects an affinity between himself and Hanley — both of them (surprisingly in the case of Burgess) writers 'desperate at the piled-up bills and the prospect of the knock of eviction.'

Previous page

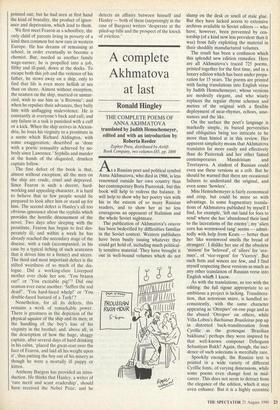

Previous page