Chirac makes the running

Sam White

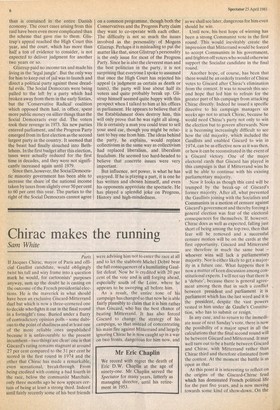

Paris If Jacques Chirac, mayor of Paris and official Gaullist candidate, would obligingly twist his tall and wiry frame into a question mark he would, for cartoonists' purposes anyway, sum up the doubt he is casting on the outcome of the French presidential elections. He is the maverick in what should have been an exclusive Giscard-Mitterrand duel but which is now a three-cornered one to decide who fights it out in the final round in a fortnight's time. Buried under a flurry of contradictory opinion polls — some dubious to the point of shadiness and at least one of the more , reliable ones unpublished because it is unfavourable to the present incumbent —two things' are clear: one is that Giscard's rating remains stagnant at around 27 per cent compared to the 31 per cent he scored in the first round in 1974 and the other that Chirac has made a remarkable, even sensational, breakthrough. From being credited with coming a had fourth in the race, below the communist Marchais, only three months ago he now appears certain of being at least a strong third. Indeed until fairly recently some of his best friends were advising him not to enter the race at all and to let the stubborn Michel Debre bear the full consequences of a humiliating Gaullist defeat. Now he is credited with 20 per cent of the vote and is still forging ahead, especially south of the Loire, where he appears to be sweeping all before him.

As a result, the entire tone of his campaign has changed so that now he is able fairly plausibly to claim that it is him rather than Giscard, who has the best chance of beating Mitterrand. It has also forced Giscard to change the strategy of his campaign, so that instead of concentrating his main fire against Mitterrand and largely ignoring Chirac he is now caught up in a war on two fronts, dangerous for him now, and as we shall see later, dangerous for him even should he win.

Until now, his best hope of winning has been a strong Communist vote in the first round. This would inevitably create the impression that Mitterrand would be forced to accept Communists in his government, and frighten off voters who would otherwise support the Socialist candidate in the final round.

Another hope, of course, has been that there would be an orderly transfer of Chirac votes to Giscard after Chirac's elimination from the contest. It was to nourish this second hope that led him to refrain for the greater part of his campaign from attacking Chirac directly. Indeed he issued a specific directive to his campaign managers six weeks ago not to attack Chirac, because he would need Chirac's party not only to win the election but to govern afterwards. Now it is becoming increasingly difficult to see how the old majority, which included the Gaullists and enabled Giscard to win in 1974, can be as effective now as it was then, or how it can be reconstituted in the event of a Giscard victory. One of the major electoral cards that Giscard has played in this campaign is that if Mitterrand wins he will be able to continue with his existing parliamentary majority.

Now it looks as though this card will be trumped by the break-up of Giscard's former majority. After all, what prevented the Gaullists joining with the Socialists and Communists in a motion of censure against Giscard's government and thereby forcing a general election was fear of the electoral consequences for themselves. If, however, Chirac does as well as expected, falling just short of being among the top two, then that fear will be removed and a successful censure motion will be on the cards at the first opportunity. Giscard and Mitterrand are therefore in much the same boat — whoever wins will lack a parliamentary majority. Nor is either likely to get a majority in a future one. What happens then is now a matter of keen discussion among constitutional experts. I will not say that there is a 'debate', because there is general agreement among them that in such a conflict between president and parliament it is parliament which has the last word and it is the president, despite the vast powers vested in him under de Gaulle's Constitution, who has to submit or resign.

In any case, and to return to the immediate issue of next Sunday's vote, there is now the possibility of a major upset in all the calculations that the final second round will be between Giscard and Mitterrand. It may well turn out to be a battle between Giscard and Chirac, with Mitterrand rather than Chirac third and therefore eliminated from the contest. At the moment the battle is as open as that.

At this point it is interesting to reflect on the origins of the Giscard-Chirac feud which has dominated French pOlitical life for the past five years, and is now moving towards some kind of show-down. On the face of it no one could be in a weaker position to assail Giscard than Chirac who, after all, was largely instrumental in getting him elected in the first place, deserting the official Gaullist candidate, Chaban-Delmas, in order to do so. He was rewarded with the prime ministership as a result, a post which he held for two years before resigning rather than waiting to be sacked.

Conflicts between the president and his chosen prime minister have been a standard feature of the history of the Fifth Republic. There was, to mention only two, the one between de Gaulle and Pompidou followed by one between Pompidou and ChabanDelmas. In no previous case, however, were matters taken to the point of open opposition and direct challenge. The present one arose because it soon became evident to Chirac that he was prime minister in name only, while the real power was shared between Giscard and his crony Prince Poniatowski, an old enemy of the Gaullists and appointed, on the President's insistence, Minister of State and Minister of the Interior. This was not the only appointment to his government imposed on Chirac — others were to follow, all of them anathema to the Gaullists and to Chirac personally. Then it began to dawn on Chirac that his appointment as Prime Minister was only a cover and that behind this cover the aim was to destroy his political base, the Gaullist party.

'As from today a new era has commenced', Giscard announced on the day of his election and the new era clearly would mark the end of the old Gaullist one. Not wishing to be ranged among the new President's other hunting trophies. Chirac resigned, carefully choosing an issue of economic policy on which to do so. Since then the battle between the two has ebbed and flowed with Chirac having his setbacks and his victories, the most notable being his capture of Paris over Giscard's nominee for mayor. Meanwhile in his present campaign it is not altogether unfair to say that Chirac has taken on something C)f the air of a larger than life Poujade — smoother, more sophisticated and with vaster resources of money and organisation than the man who led the small shopkeepers revolt in 1954, but basically drawing his support from the same sources in town and country.

Small farmers — which explain his success in the south and south west — small industrialists, the middle categories of civil servants and professional men, and of course small shopkeepers: these are the ones who most readily identify themselves with him and his attacks on the technocrats in Paris. (He himself is no mean technocrat being, like Giscard, a graduate of that school for the civil service elite ENA, but unlike Giscard he does not speak like one.) Meanwhile although my money is still on Giscard, what seemed like being a dull election with a foreseeable outcome has become a tense one, and what seemed like a settled future for France has turned into the likelihood of an uncertain one.

Previous page

Previous page