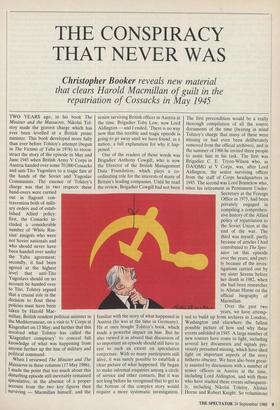

THE CONSPIRACY THAT NEVER WAS

that clears Harold Macmillan of guilt in the repatriation of Cossacks in May 1945

TWO YEARS ago, in his book The Minister and the Massacres, Nikolai Tol- stoy made the gravest charge which has ever been levelled at a British prime minister. This book developed more fully than ever before Tolstoy's attempt (begun in The Victims of Yalta in 1978) to recon- struct the story of the episode in May and June 1945 when British Army V Corps in Austria handed over some 70,000 Cossacks and anti-Tito Yugoslays to a tragic fate at the hands of the Soviet and Yugoslav Communists. The essence of Tolstoy's charge was that in two respects these hand-overs were carried out in flagrant con- travention both of milit- ary orders and of estab- lished Allied policy: first, the Cossacks in- cluded a considerable number of 'White Rus- sian' émigrés who were not Soviet nationals and who should never have been handed over under the Yalta agreement; secondly, it had been agreed at the highest level that anti-Tito Yugoslays should on no account be handed over to Tito. Tolstoy argued that a crucial role in the decision to flout these policies must have been taken by Harold Mac- millan, British resident political minister in the Mediterranean, on a visit to V Corps at Klagenfurt on 13 May; and further that this involved what Tolstoy has called the `Klagenfurt conspiracy' to conceal full knowledge of what was happening from anyone further up the line of military and political command.

When I reviewed The Minister and The Massacres in these columns (17 May 1986), I made the point that too much about this disturbing episode still inevitably remained speculative, in the absence of a proper account from the two key figures then surviving — Macmillan himself, and the senior surviving British officer in Austria at the time, Brigadier Toby Low, now Lord Aldington — and I ended, 'There is no way now that this terrible and tragic episode is going to go away until we have found, as a nation, a full explanation for why it hap- pened.'

One of the readers of those words was Brigadier Anthony Cowgill, who is now the Director of the British Management Data Foundation, which plays a co- ordinating role for the interests of many of Britain's leading companies. Until he read the review, Brigadier Cowgill had not been familiar with the story of what happened in Austria (he was at the time in Germany). He at once bought Tolstoy's book, which made a powerful impact on him. But he also viewed it as absurd that discussion of so important an episode should still have to rest to such an extent on speculative conjecture. With so many participants still alive, it was surely possible to establish a clear picture of what happened. He began to make informal enquiries among a circle of service and other contacts. But it was not long before he recognised that to get to the bottom of this complex story would require a more systematic investigation. The first precondition would be a really thorough compilation of all the source documents of the time (bearing in mind Tolstoy's charge that many of these were missing or had even been deliberately removed from the official archives), and in the summer of 1986 he invited three people to assist him in his task. The first was Brigadier C. E. Tryon-Wilson who, as DA/QMG at V Corps, was, after Lord Aldington, the senior surviving officer from the staff of Corps headquarters in 1945. The second was Lord Brimelow who, since his retirement as Permanent Under- Secretary at the Foreign Office in 1975, had been privately engaged in compiling a comprehen- sive history of the Allied policy of repatriation to the Soviet Union at the end of the war. The third was myself, partly because of articles I had contributed to The Spec- tator on this episode over the years, and part- ly because of the inves- tigations carried out by my sister Serena before her death in 1982, when she had been researcher to Alistair Home on the official biography of Macmillan.

Over the past two years, we have attemp- ted to build up from archives in London, Washington and elsewhere the fullest possible picture of how and why these events unfolded in 1945. A large number of new sources have come to light, including several key documents and signals pre- viously presumed missing, which have shed light on important aspects of the story hitherto obscure. We have also been great- ly assisted by discussions with a number of senior officers in Austria at the time, including Lord Aldington, and with those who have studied these events subsequent- ly, including Nikolai Tolstoy, Alistair Home and Robert Knight. So voluminous is the documentation we have collected that we hope eventually to publish a full report, including facsimiles of all relevant sources. But an interim report is to be made public this week.* AS OUR investigation proceeded, we found that in two fundamental respects it changed the whole perspective in which these events have previously been pre- sented.

The first was that far too little account had been taken of the critical military and political situation in which the Allied Forces under Field Marshal Alexander found themselves as the war came to an end in early May 1945. As units of the Eighth Army advanced into Venezia Giulia, around Trieste, and Carinthia in southern Austria, they were confronted by large numbers of Yugoslav partisans, aggressively pursuing Tito's claim that both territories should be included in a 'Greater Yugoslavia'. In Austria in particular General Keightley's V Corps faced a situa- tion of near chaos. Not only was the area clogged with nearly half a million POWs and refugees of many different nationali- ties, but Tito's partisans were attempting to set up a rival military administration and on 10 May Keightley asked for permis- sion to shoot, if necessary, at Yugoslays.

What neither Keightley nor General McCreery at the Eighth Army and the commander of XIII Corps to the south of him in Italy realised was just how grave an international crisis this situation was threa- tening to become. Alexander at Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) was now having to contemplate a full-scale war with Tito, in which (a) he might not have the military support of the Americans and (b) the Soviet Red Army nearby might come to Tito's aid. On 12 May, at Alexander's request, Macmillan flew north on an ur- gent mission to brief the front-line com- manders on the need not to provoke the Yugoslays prematurely before all units were in a state of operational readiness for hostilities which might soon be necessary.

This was why Macmillan went to Klagenfurt on 13 May. Macmillan briefed Keightley on the general situation, and was told in turn of V Corps' problems with the Yugoslav partisans, and with the huge mass of refugees and prisoners in the area who could only hamper military opera- tions. It was in this context that Macmillan was informed of the presence among the surrendered Germans of various forma- tions of Cossacks — the one group of prisoners who could be removed from the area fairly quickly since, as Macmillan advised, the British were obliged under the Yalta agreement to hand over all Soviet citizens to the Soviet authorities.

Here we come to the second, even more important respect in which our investiga- tions have led to a totally new perspective. Ever since Macmillan's role in this affair first became a matter of controversy in the Seventies, it has been assumed that by the time he went to Klagenfurt on 13 May the presence of White Russian emigres among the Cossacks was known to pose a particu- lar problem, and that everyone involved was familiar with the policy that, as 'non- Soviet nationals', such emigres should not be handed over.

In fact, as our investigations have shown, neither of these things was the case. Not only was information about the Cossacks still very vague at this point. More important, there was actually no- thing in Allied policy instructions at this time, as we have discovered, to signal that émigré Russians as such should not be repatriated. The only instruction on this matter available to Macmillan or anyone else was a letter interpreting Allied obliga- tions under Yalta sent to AFHQ on 6 March.

Although Tolstoy makes extensive re- ference to this 6 March letter (and to a later instruction allegedly sent on 6 May), it was only subsequent to the publication of The Minister and The Massacres that an actual copy of this all-important instruction was obtained from archives in Washington (and the 6 May instruction, it turns out, never existed — it was a typing error for 6 March). When the 6 March letter, defining who was or was not a Soviet citizen liable for repatriation, is examined, it says no- thing which could signal to British units that emigres who had left the Soviet Union before the war should not be repatriated. Its sole preoccupation (and this is in accordance with all the discussions of which we have found record in 1944 and early 1945) is with people coming from those territories of Poland and the Baltic States which had been forcibly incorpo- rated into the Soviet Union after 1 Septem- ber 1939. Strictly within the terms of the 6 March letter, it would seem that pre-1939 émigrés from the Soviet Union might be considered just as eligible for repatriation as those who had left during the war.

We have in fact found no evidence that, 'Look's like you've hit the jackpot or son.' by the time of Macmillan's arrival at Klagenfurt, the possibility that any special problem might be posed by the presence of old émigrés among the Cossacks had en- tered anyone's mind. All discussions of the future of the Cossacks at this stage were considered purely in general terms should they or should they not be sent back as a whole? And it was not only Macmillan who advised that, under Yalta, we were obliged to hand them back. When Macmil- lan's US opposite number at AFHQ, Alex- ander Kirk, asked on 15 May for urgent comment from Washington on the decision to hand over the Cossacks, in a telegram which Tolstoy has made much of, we have now discovered that Kirk did in fact get a reply the same day, agreeing to the hand- over. When Alexander asked the chiefs of staff for their view on 17 May, the reply from both them and the Foreign Office was the same — the Cossacks should be handed over. In short, in the terms in which the question was put to him on 17 May, Macmillan gave an answer which was echoed by everyone else to whom the same question was put.

The question which remains is, if no one was worried about emigres at the time of Macmillan's visit, when did this problem which has inspired so much of the con- troversy of recent years begin to surface? The answer is that, as preparations were made for the actual hand-overs, questions did begin to be asked about the precise liability to repatriation of the various groups of Russians involved. As a result, by the time the final list was drawn up on 21 May, two of the six formations had been ruled as not eligible for repatriation, the Schutzkorps, which consisted largely of old `White Russian' émigrés who had lived in the Balkans before the war, and were holders of non-Soviet passports; and the First Ukrainian Division, whose members came mainly from territories which on 1 September 1939 were Polish (this was in accordance with the 6 March letter). These were the only two in which 'non-Soviet nationals' formed a majority. Five Corps took the decision to screen only on a 'formation basis' because it was considered that, in the operational situation, it would have been impracticable to carry out more detailed screening. Provision was made in the relevant order on 21 May for individual cases to be retained if they were sufficient- ly strongly pressed, and in the event this resulted in a small number of émigrés holding non-Soviet passports being pulled off the transports on their way to hand- over. But the intention of the 21 May order was to ensure that the greatest number of Cossacks were handed over, with as little practical complication as possible. The fact that this resulted in a good many non- Soviet nationals, including Germans, being handed over was the result of a military, not a political decision, of which Macmil- lan was wholly unaware.

So far as the anti-Tito Yugoslays were concerned — various groups of Chetniks, Slovenes and others who, under Allied policy, should not have been handed over — there is now overwhelming evidence that Macmillan gave no advice at all on their disposal, and that he was therefore in no way involved in the sequence of events which, beginning from an order issued by V Corps on 17 May, led to their eventual return to a grim fate in Yugoslavia.

In general therefore it is the unanimous finding of our enquiry (in this respect all four members of our group ended with a different view from the one each began with) that Harold Macmillan was in no sense knowingly a party (a) to handing over of non-Soviet nationals among the Cossacks; (b) to orders relating to the handing over of Yugoslays against Allied policy; (c) to any 'Klagenfurt conspiracy'. On all these counts, our view is that Macmillan is completely cleared from any of the charges which have been levelled against him in respect of the events in Austria in 1945.

If it is asked, why did Macmillan himself not give a satisfactory reply to these charges before his death, the short answer is that his memory of what had happened was so confused, that he could not remem- ber specifically what he had been told or had agreed to 40 years earlier. Although he attempted in 1980 to get some official clarification, he never had the facts made available to him that would have enabled him to give a proper answer to the charges.

This leaves, however, the remainder of the story, and here our conclusions may be summarised as follows. Throughout the period when the decisions to hand over the Cossacks and Yugoslays were taken, the overriding requirement for V Corps was, in Alexander's words in a signal on 16 May, to 'clear the decks', to get rid of prisoners wherever possible in order to clear lines of communication and to achieve operational readiness for possible action against Tito. This accounted for why the screening of the Cossacks was not conducted as scrupu- lously as might have been the case in other circumstances; and also for the order on 17 May whereby V Corps set in train the hand-overs of Yugoslays who, under Allied policy which was repeatedly con- firmed throughout the relevant period, should have been retained pending a poli- tical decision on their ultimate disposal.

By 23 May V Corps was in a position where it was still having to press for final authorisation from the Eighth Army and AFHQ to hand over both Cossacks and Yugoslays — and in each case the order finally given was that they could be handed over so long as force did not have to be used.

The tactic which V Corps used in an effort to obviate the use of force was deception. Both Cossacks and Yugoslays were given the impression, as they were loaded onto transports, that they were being taken to safe destinations — and in each case, had the hand-overs been com- pleted quickly, this ruse might have work- ed. But in each case it was in the nature of the operation that, eventually, the decep- tion would be seen through, the victims would recognise the fate in store for them and force would have to be used. This happened both in the case of various groups of Cossacks and of the last groups of Yugoslays, when British troops resorted to considerable violence, involving a num- ber of deaths. This eventually led to the halting of the repatriation operations and to an army enquiry into events which many British soldiers involved had found deeply disturbing. They had been asked to carry out orders, involving both deception and brutality, which were quite outside any- thing else in their military experience, and which seemed to run counter to all those traditions and values for which they had fought the war.

It is in this respect that the events in Austria in May and June 1945 have rightly become the subject of great historical interest and public concern in recent years, and for his part in presenting a vivid picture of these events Nikolai Tolstoy has performed a signal public service. But his attempt to involve Harold Macmillan in a `Klagenfurt conspiracy' is entirely baseless, and to the extent that this has diverted attention from the realities of a tragic story, it can only be regretted.

Previous page

Previous page