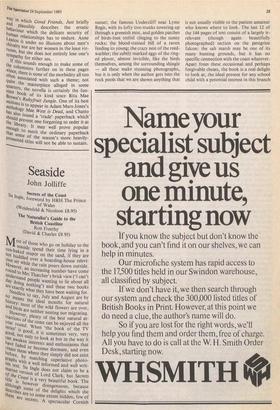

Seaside

John Jolliffe

Secrets of the Coast

Su Ingle, foreword by HRH The Prince of Wales (Weidenfeld & Nicolson £8.95) The Naturalist's Guide to the British Coastline

Ron Freethy (David & Charles £9.95)

Most of those who go on holiday to the seaside spend their time lying in a sun-baked stupor on the sand, if they are not huddled over a boarding-house televi-

sion set whi the rain pours down . However, anle increasing number have come round to Mrs Thatcher's brisk view CI can't understand people wanting to lie about all day doing nothing') and these two books are exactly what they have been waiting for.

Needless to say, July and August are by nho. Means the ideal months for natural Istory: most of the wild flowers are over, and birds are neither nesting nor migrating. However, Plenty of the best natural at- tractions of the coast can be enjoyed all the Year round. When 'the book of the TV geriesood

Is good, it is sometimes very, very

, not only to look at but in the way it have f nawaken interests and enthusiasms that

w faded or become dormant, and even b ,eforecreate them where they simply did not exist

, by matching superlative photo- graphs with a well informed and well writ- len text, Su Ingle does not claim to be a Marine version of Lord Clark, but Secrets title is °I the Coast is a very beautiful book. The however disingenuous, because although some of the delights which she them ar ome extent hidden, few of

sunset; the famous Undercliff near Lyme Regis, with its lofty tree-trunks towering up through a greenish mist, and golden patches of birds-foot trefoil clinging to the sunny rocks; the blood-stained bill of a raven feeding its young; the crazy nest of the reed- warbler; the subtly marked eggs of the ring- ed plover, almost invisible, like the birds themselves, among the surrounding shingle — all these make stunning photographs, but it is only when the author gets into the rock pools that we are shown anything that

is not usually visible to the patient amateur who knows where to look. The last 12 of the 144 pages of text consist of a largely ir- relevant (though again beautifully photographed) section on the peregrine falcon: the salt marsh may be one of its many hunting grounds, but it has no specific connection with the coast whatever. Apart from these occasional and perhaps forgivable cheats, the book is a real delight to look at, the ideal present for any school child with a potential interest in this branch

of natural history. The Prince of Wales, in a brief foreword, refers to the efforts made by the Duchy of Cornwall to provide for wild life by establishing nature reserves, in particular the marine reserve in the Scilly Isles.

Su Ingle's book will whet the appetite for The Naturalist's Guide to the British Coastline by Ron Freethy, a less immediate- ly attractive book, but a far meatier one, the author being Editor to the British Naturalists' Association, and Head of Science at a school in Lancashire. Always instructive, and only occasionally didactic in tone, it covers a much wider field at far greater depth, and only costs a pound more. Many examples could be given of the interesting and (to me) unfamiliar informa- tion conveyed: did you know how effective- ly the so-called balance of nature operates in the case of ragwort and the caterpillars of the cinnabar moth? When there are plenty of caterpillars they attack the ragwort so heavily that few seeds set. Next year, fewer plants, fewer larvae, and the ragwort recovers. (I have also seen them chewing up the groundsel in pleasing fashion in my own garden last month, so they are not too choosy.) The author also delightfully describes his discovery, as a wartime child, that the hips of the burnet rose (Rosa Spinosissima) fetched fourpence a pound, compared with threepence a pound for the fruits of the dog-rose and the field-rose, for conversion into rose-hip syrup, rich in vitamin C, at a time when fruit could not be imported. The burnet rose grew abun- dantly on his native Cumbrian sand-dunes, and, as he says, the four-times table can never have been mastered so agreeably.

He also mentions the improvement of the British climate over the last century: cooler summers and milder winters have reduced the need for long migratory voyages for many kinds of waterfowl, with the result that a number of varieties have become nesting residents. Nor did I appreciate how vulnerable are the nests of ringed plover and little terns in the shingle. If the parent birds are disturbed by beach anglers or casual holiday makers in cold or wet weather, the eggs will chill in the absence of the brooding parent, and the embryos will perish; whereas on a hot, sunny day the un- protected eggs may be baked by the heat of the sun on the surrounding stones and may likewise fail to hatch.

The book is very sensibly constructed, in that each chapter describes a different seaside habitat: cliffs, estuaries, salt mar- shes, shingle, sand, rocks and islands. It ends with a chapter on the conflicting needs of coastal wildlife and industry which is a model of balanced good sense, avoiding the shrill cries of unrealistic conservationists and paying tribute to the efforts of (for ex- ample) ICI's laboratory at Brixham to solve a wide range of environmental problems in an imperfect and hungry world. Finally, it would be wrong not to mention Carol Pugh's quite excellent line illustrations, which prove that great accuracy need not be a barrier to imagination and style.

Previous page

Previous page