THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

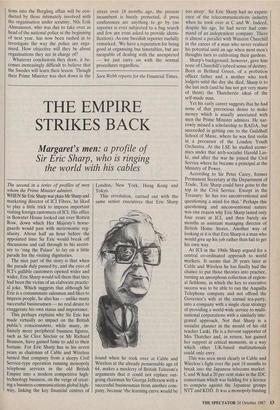

Margaret's men: a profile of

Sir Eric Sharp, who is ringing the world with his cables

The second in a series of profiles of men whom the Prime Minister admires.

WHEN Sir Eric Sharp was plain Mr Sharp and marketing director of ICI Fibres, he liked to play a little trick to impress important visiting foreign customers of ICI. His office in Bowater House looked out over Rotten Row, down which Her Majesty's horse- guards would pass with metronomic reg- ularity. About half an hour before the appointed time Sir Eric would break off discussions and call through to his secret- ary to 'ring the Palace' to lay on a little parade for the visiting dignitaries.

The nice part of the story is that when the parade duly passed by, and the eyes of ICI's gullible customers opened wider and wider, Eric Sharp would tell them that they had been the victim of an elaborate practic- al joke. Which suggests that although Sir Eric is a consummate salesman and likes to impress people, he also has — unlike many successful businessmen — no real desire to exaggerate his own status and importance.

This perhaps explains why Sir Eric has made virtually no impact on the British public's consciousness, while many, in- finitely more peripheral business figures, such as Sir Clive Sinclair or Mr Richard Branson, have gained fame to add to their fortune. For Eric Sharp has in his seven years as chairman of Cable and Wireless turned that company from a sleepy Civil Service-type operation running monopoly telephone services in the old British Empire into a modern competitive high- technology business, on the verge of creat- ing a business-communications global high- way, linking the key financial centres of London, New York, Hong Kong and Tokyo.

This revolution, carried out with the same senior executives that Eric Sharp found when he took over at Cable and Wireless at the already pensionable age of 64, makes a mockery of British Telecom's arguments that it could not replace out- going chairman Sir George Jefferson with a successful businessman from another com- pany, because 'the learning curve would be too steep'. Sir Eric Sharp had no experi- ence of the telecommunications industry when he took over at C and W. Indeed, despite his age, he had never had com- mand of an independent company. There is almost a parallel with Winston Churchill in the career of a man who never realised his potential until an age when most men's thoughts turn to cultivating their gardens.

Sharp's background, however, gave him none of Churchill's inbred sense of destiny. Born in Bethnal Green, of a probation officer father and a mother who took lodgers until the day she died, Sharp is to the last inch (and he has not got very many of them) the Thatcherite ideal of the self-made man.

Yet his early career suggests that he had none of that precocious desire to make money which is usually associated with men the Prime Minister admires. He nar- rowly missed a scholarship to RADA, but succeeded in getting one to the Guildhall School of Music, where he was first violin in a precursor of the London Youth Orchestra. At the LSE he studied econo- mics under that arch-socialist Harold Las- ki, and after the war he joined the Civil Service where he became a principal at the Ministry of Power.

According to Sir Peter Carey, former Permanent Secretary at the Department of Trade, 'Eric Sharp could have gone to the top in the Civil Service. Except in the Treasury: he has too unconventional and questioning a mind for that.' Perhaps this questioning and unconventional nature was one reason why Eric Sharp lasted only four years at ICI, and then barely six months as assistant managing director of British Home Stores. Another way of looking at it is that Eric Sharp is a man who would give up his job rather than fail to get his own way.

At ICI in the 1960s Sharp argued for a central co-ordinated approach to world markets. It seems that 20 years later at Cable and Wireless he has finally had the chance to put those theories into practice, turning an amorphous collection of region- al fiefdoms, in which the key to executive success was to be able to run the Anguilla Telephone company and not offend the Governor's wife at the annual tea-party, into a company with a single clear strategy of providing a world-wide service to multi- national corporations with a similarly inte- grated approach. Not that Sharp is a socialist planner in the mould of his old teacher Laski. He is a fervent supporter of Mrs Thatcher and, in return, has gained her support at critical moments, in a way which other UK-based multinationals could only envy.

This was seen most clearly in Cable and Wireless's fight over the past 18 months to break into the Japanese telecoms market. C and W had a 20 per cent stake in the IDC consortium which was bidding for a licence to compete against the Japanese groups Nn- and KDD. It was a monopoly-busting attempt which would dwarf Cable and Wireless's earlier — and successful efforts to challenge British Telecom with the Mercury project. The Japanese govern- ment said that it would accept the consor- tium led by C and W only if the group was watered down with the inclusion of a number of Japanese companies. Hardened Tokyo watchers said that Cable and Wireless's initiative was doomed. They reckoned without Sir Eric's friend.

Mrs Thatcher personally lobbied the Japanese prime minister, Mr Nakasone, and warned that if Japan refused to 'com- promise' then retaliatory action would be taken against Japanese telecommunica- tions exports to the UK, and that UK banking licences granted to Japanese securities houses would be withdrawn. This last threat was, of course, way over the top, and dismayed the Bank of England. But it illustrated the extent to which Sir Eric had fired up the Prime Minister. Last month the Japanese threw in the towel and `invited' the Cable and Wireless consor- tium to bid for the cherished licence.

It was not the first time that Eric Sharp had proved the adage that contrary think- ing is the best way to make a business killing. Just as few imagined that a foreign consortium stood a chance in Japan hence the absence of really strong US competition for the contract — so also was Cable and Wireless's attempt to break BT's monopoly written off at an early stage. Indeed it was written off by Cable's partners. In August 1984 BP sold its 40 per cent stake in Mercury to C and W for £30 million. Stock market analysts today reck- on that Mercury, now wholly owned by C and W, is worth about £1 billion.

A similar triumph for contrary thinking was Eric Sharp's swoop to take over Hong Kong Telephone. It was a raid carried out during a slump in the Hong Kong stock market at a time of obsession with the '1997 problem'. It cost C and W about £300 million to seize control. Last week it announced plans to hive off its Hong Kong operations into a separately quoted com- pany which will be capitalised at about £4 billion.

Yet it would be wrong to infer from this dazzling piece of footwork that Sir Eric is a stock market wizard who spends his time thinking about the Cable and Wireless share price. He is, in the good old- fashioned sense of the word, an industrial- ist. He is not an assiduous wooer of stock market analysts — he has their respect rather than their friendship. Still less is he one to confide anything to financial jour- nalists, in the hope of favourable publicity.

Nor, it seems, is he particularly in- terested in personal enrichment. Although his salary is now a more than comfortable £239,000, and the gearing of his share options to C and W's runaway share price has made him a wealthy man, he still lives in the same unostentatious Stanmore house that he acquired in 1970. There is no house in the country. There is no yacht. And he has been married to the same woman, Marion, for 36 years. As that suggests, he is the archetypal family man, who visibly takes as much pride in the successes of his two surviving children as he does in any of his own achievements.

However, Eric Sharp has no intention of retiring to spend all his time with his family. Even at the age of 71 he still has a prodigious, energy. Mr David Clementi of Kleinwort Grieveson, who has advised Sir Eric on a number of his deals, says that 'he keeps a diary which would make a man half his age wilt'.

Yet in the City and among the non- executive directors of Cable and Wireless, there is a growing fear that, in common with some other tycoons who work fero- ciously and lead from the front, Sir Eric has not spent as much time as he should have done grooming a successor. Two men who may have thought that they were in the running, Mr Alan Wheatley, the for- mer deputy chairman, and Mr Ernest Potter, erstwhile finance director, have fallen by the wayside. Sir Eric's question- ing mind, it seems, does not extend to questioning the permanency of his own tenure of the jobs of chairman and chief executive.

But it is easy to see the argument from Sir Eric's point of view. He is enjoying himself enormously in a position which he has held for only seven years. After almost a lifetime of waiting for the right job, it is a bit hard to give it up that soon. Moreover Sir Eric is a keen student of — and business partner with — the People's Republic of China, and probably reckons himself an infant beside Deng Hsiao Ping.

Indeed there is something oriental about Sir Eric's business strategy. He is not so much a player of chess — a rather tactical Western game — but of Go, an Eastern board game in which the object is imper- ceptibly to surround the target. In Sir Eric's case the target is the world, which he is slowly but surely enmeshing with his cables.

Previous page

Previous page