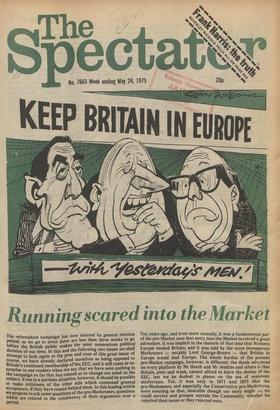

Running scared into the Market

The referendum campaign has now entered its general election period: as we go to press there are less than three weeks to go before the British public makes the most momentous political decision of our time. In this and the following two issues we shall attempt to look again at the pros and cons of this great issue: of course, we have already declared ourselves as being opposed to Britain's continued membership of the EEC, and it will come as no sorpnse to our readers when we say that we have seen nothing in the campaign so far that has caused us to change our mind on the subject. Even In a partisan situation, however, it should be possible to make criticisms of the other side which command general acceptance, if they have reason behind them. In this leading article we propose to ask some questions of the pro-Marketeers, questions Which are related to the consistency of their arguments over a period. Ten years ago, and even more recently, it was a fundamental par' of the pro-Market case that entry into the Market involved a great adventure. It was implicit in the rhetoric of that time that Western Europe needed Britain; and it was said by the more intemperate Marketeers — notably Lord George-Brown — that Britain in Europe would lead Europe. The whole burden of the present pro-Market campaign, however, is different: the thesis advE,nced on every platform by Mr Heath and Mr Jenkins and others i that Britain, poor and weak, cannot afford to leave the shelter of the EEC, lest we be dashed to pieces on the sea of economic misfortune. Yet, it was only in 1971 and 1972 that the pro-Marketeers, and especially the Conservative pro-Marketeers, were assuring us that, desirable though our entry might we could survive and prosper outside the Community, whether we rejected their terms or they rejected ours. Several questions arise at this point. Have world conditions changed so greatly — beyond the power of our politicians — that the high optimism of only a few years ago is no longer applicable, and that we must seek to be pensioners of our Western European allies? Or is it, perhaps, that predominantly pro-Market Labour and Conservative governments so mishandled this country's affairs as to bring us to our present pass; and if that is so should the judgement of the same men be trusted again? Even if it is said that circumstances beyond the control of our politicians have caused our present problems, and command us to remain within the EEC, surely it would not be unreasonable to have expected a certain amount at least of prevision of those circumstances, if we are to expect anything at all of the skill of our leaders? Yet it was as recently as late 1973 that Mr Heath and Mr Peter Walker were insisting that the problems of Britain were "the problems of success". In what way, we would like to know, have the senior politicians now supporting our continued membership of the EEC demonstrated ability, or achieved real success, in their ministerial careers? Of course, the evidence that answers to these questions would provide would be no more than empirical: but empirical evidence is the evidence of experience, and experience is the proving ground of politics.

Another question arises here. To be perfectly fair to them, pro-Market campaigners of the 'sixties and early 'seventies never pretended that entry into the EEC would produce an instant cornucopia: they were honest in saying that the real advantages of membership would be some time in coming. But, now that we have entered the EEC, and now that we have been members for some time, it should surely be possible to indicate at least a ghostly outline of advantage: there should be some indication that we will get something out of the thing, even in the long run. The staggering fact, nonetheless, is that our balance of trade with the member countries of the EEC was better before entry than it is now, and that it gives every indication of further decline. Even the considerable charity — and we ought to be grateful for it — which our EEC partners have shown in their dealings with us cannot conceal the fact that in almost every department of trade we have lost out during our period of membership. Could the proponents of continued membership give some solid evidence of when things will get better?

Pro-Marketeers, it seems to us, are much less honest about the balance between the economic and the political consequences of entry than they once were. Years ago both Mr Macmillan and Lord GeorgeBrown were frank in saying that the argument for entry was political rather than economic: only by such a formulation could the economic disadvantage be offset in the present argument. Now, the political argument has taken place around the concept of sovereignty. But, if the pro-Marketeers are long-term thinkers — as they have professed themselves to be — should they not say what they envisage the long-term political future of a united Western Europe as being? The anti-Mar keteers say that the end result will be a federal state dominated by a Brussels bureaucracy; and they say, further, that the evil end which this would be is not compensated for by any likely economic advantage for the ordinary citizen. Are the pro-Marketeers federalists? And if they are not, what are they?

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the pro-Market case is now — as it was not always — based on fear. The entire intellectual and moral resources of Mr Heath and Mr Jenkins and the others seem to consist in a warning to the British people that they dare not leave the Market, that they dare not trust themselves. Stripped of its rhetoric that is the proMarket case. It is up to the people to decide whether they have the moral resources to defy the argument.

Previous page

Previous page