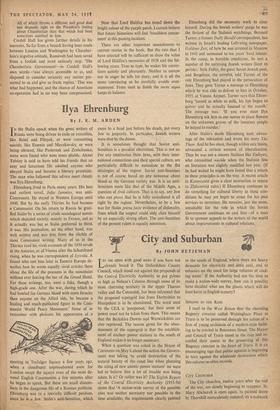

II: Destroying the Myths

By LORD TEMPLEWOOD musr follow the Parliamentary convention land, before I discuss this volume of memoirs, disclose my personal interest in it. Lord Halifax and I have been close friends for half a century and in the governments of which we have been members we have almost always agreed with each other on the more important questions. I cannot, therefore, claim to be impartial. Perhaps, however, the intimacy of many years, by adding a personal interest to my comments, will make up for any bias in my judgement.

The memoirs of anyone who has held many great posts in public life are bound to be episodic. The scene changes as a Minister passes from one office to another, and unless there is some thread to hold them together the result is a newsreel rather than a story with a plot.

In the case of Lord Halifax, the connecting link between Yorkshire and Oxford, India and Whitehall, the Foreign Office and Washington is the wens (equa that remains unruffled whatever the place and the circumstances. There is scarcely a page of this book that does not illustrate the consistency of .a career that has been throughout founded upon the particularly English qualities of good nature and commori sense. if the scenes are different, the signature tune of the principal actor remains the same.

I pass by the family story, pleasant as it is. The Whig tradition of the Grays of Howick, the mellow amenities of Powderham, the life of great Yorkshire landowners, the unique figure of his saintly father and the abiding influence of his serene mother—these form the attractive back- ground for the curses honorum that he has com- pleted with an ease that has seemed effortless. It is rather to certain incidents in his public career that I wish specially to refer.

It is now twenty years since the start of his Foreign Secretaryship and the days of Munich. A new generation has arrived that knows none of the hopes and fears of 1938. Events that then stirred the waters of political life into a raging storm are now passing into the calmer depths of history. It is essential, therefore, to clear the story of as many inaccuracies and irrelevancies as possible, and to leave the main issue between the disputants simple and definite for future judgement.

As to whether or not we should have gone to war in 1938 rather than in 1939 there will always be profound differences of opinion. Many will sincerely believe that we committed a terrible mistake by refusing Hitler's challenge at the time of Munich. Others will remain convinced that we were right to postpone the clash until our Hurri- canes, Spitfires and radar were ready and we could rely upon a united front in the Common- wealth. Between these two views there may now be no bridge, but that is no reason why the arguments on each side should be bolstered up with partisan inventions.

One of the great merits of Lord Halifax's book is that' it definitely removes a number of the props that have been sedulously built up on one side of the controversy. I take two of these props as examples of what I mean.

I begin with the attacks on Neville Chamber- lain. He may not have been a popular leader, least of all a war leader. He was too shy, too critical of stupid things and stupid people, too efficient, in fact, at a time when the world was not asking for efficiency, but for an inspiring appeal. But the myth that has grown up around him bears little relation to the real man. If it were permanently believed, he would go down in history as an ignorant and incompetent Prime Minister who usurped the functions of his Foreign Secretary, and at a critical moment earned the lasting resentment of the United States of America.

What has Lord Halifax, the man most likely to know the truth, to say about these charges? I quote one of the paragraphs in which he deals with the Prime Minister's part in foreign policy : It has been repeatedly asserted that Chamber- lain interfered unduly with the work of the Foreign Secretary and of his office through the unwelcome intervention of Sir Horace Wilson. I can only say that during the period of more than two years that I was at the Foreign Office under Chamberlain, I had no such experience. So far from feeling that Horace Wilson inter- fered and made things difficult between Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary, I always found him extremely helpful, when the pressure of work was heavy, in ensuring that I was fully acquainted with the thought of the Prime Minister, and vice versa, and that neither was unconsciously drifting into any misunderstand- ing of the other's mind. Chamberlain himself was careful to avoid saying or doing anything likely to cause me embarrassment or constitute a departure from the general line that we had usually arrived at after discussion together. I only recall one occasion when I felt bound to take exception to something that he had said to some gathering of pressmen. In the course of one of the conferences which he used to have with representatives of the press from time to time and which were quite useful both to them and to the government, he had made some reference to foreign affairs which I thought cut across our understanding and was capable of making trouble. I cannot remember exactly what it was that he had said, and it may well have been that the press representatives made a mistake in publishing or attributing to him re- marks he had not expected to be so used. But the result was tiresome for the Foreign Office, and at the time I was annoyed about it. So I reproached him, and my protest promptly pro- duced a generous apology, which both illustrates , the relations of complete confidence that pre- vailed between us and made me think the whole episode had been well worth while.

The fact was that never did a Prime Minister work better with his Foreign Secretary than Chamberlain with Halifax. Their responsibility for policy was a joint one. And it was more than the policy of a duumvirate, for with the single exception of Duff Cooper, it was steadily sup- ported throughout the Munich crisis by the whole Cabinet.

I pass on to an even more notable comment on an incident that has loomed very large in the Munich controversy. Readers of Sir Winston Churchill's The Second World War will remem- ber the scathing passage in which he describes Chamberlain's rejection of Roosevelt's alleged offer of help in January, 1938. Sir Winston has described his 'breathless amazement at the self- sufficiency of a man with Mr. Chamberlain's limited outlook waving away the proffered hand stretched out across the Atlantic.' Sir Winston was not a member of the Government at the time, and could not have followed the telegrams that' then passed between Washington and London. If he had, he would have seen that the President himself dropped the proposal of an international conference on the ground that it was inoppor- tune. His own Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, who all along thought the proposal most objec- tionable, was delighted when it was dropped. Lord Halifax says the final word on the episode when he describes an interview that he had with Roosevelt when he was in Washington as Am- bassador.

Eden was coming over for the first time, and I had gone to sec Roosevelt about the visit. The President had never met Eden and asked me a lot of questions about him. These I answered and then dilated a little upon my own regard for Eden, upon how closely we had worked to- gether, and in how public-spirited a fashion he had behaved in relation to myself after his own resignation. By way of giving what I said a somewhat personal point for the President, I told him that one of the reasons which had been quite powerful in influencing Eden's resignation from Chamberlain's Government had been the fact that he thought Chamberlain had handled badly a proposal put forward by the President while he, Eden, had been away on holiday. To all this the President listened, much as one does when one is waiting for the other person to stop in order to say something more interesting oneself. When I did stop, the President said to me, 'Did you ever see the telegram I sent to Chamberlain at the time of Munich?' I said I supposed I had seen it, but would he refresh my mind? 'The shortest telegram I ever sent,' said the President, 'two words; "Good man." ' All of which throws a different and good deal less dramatic light on the President's feeling about Chamberlain than that which had been sometimes ascribed to him.

Cordell Hull has given further details in his memoirs. So far from a breach having been made between London and Washington by Chamber- lain's negative attitude, Roosevelt had been saved from a foolish and most untimely step. 'The Chamberlain Government'—in Cordell Hull's own words—`was always accessible to us, and disposed to consider seriously any matter pre- sented to us and give us frank replies.' This was what had happened, and the chance of American co-operation had in no way been compromised. Now that Lord Halifax has toned down the bright colour of the purple patch, I cannot believe that future historians will feel 'breathless amaze- ment' at this passing incident.

There are other important amendments to current stories in the book. But the two that I have selected will be sufficient to show the value of Lord Halifax's memories of 1938 and the fol- lowing years. True to type, he makes his correc- tions quietly and pleasantly. Neither in sorrow nor in anger he tells his story, and it is all the more convincing as he carefully avoids over- statement. From start to finish the mens aqua keeps its balance.

Previous page

Previous page