ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Showing their slips

Roderick Conway Morris

Fake? The Art of Deception (British Museum, till 2 September) 0 n entering the gallery one is con- fronted with a bizarre 'Etruscan' terracotta sarcophagus. Even allowing that the Etrus- cans might simply have had extraordinary taste, it is difficult to conceive how,.despite its mass of anomalous and anachronistic features, this riotous grotesque could have remained a prize exhibit at the British Museum from 1871 until 1935, when it was finally declared `phonus bolonus' and carted off to the lumber room. But then this unusual exhibition, which runs the full gamut from bogus Greek coins and samur- ai swords to photographs of fairies at the bottom of the garden and imitation bottles of Johny Walker Black Label, tells us as much about wishful thinking as it does about mendacity. And as both the exhibi- tion and Mark Jones's lively and thought- provoking catalogue (British Museum, £16.95) amply illustrate, when it comes to fakes, experts and laymen alike have been falling flat on their faces since the dawn of time.

Faking has a long, if not exactly vener- able history. In the second millenium BC, Babylonian priests were manufacturing ancient decrees to bump up their temple's revenue from the king. In eighth-century BC Egypt, the city of Memphis was assert- ing its precedence over Heliopolis with the aid of brand-new 'antique' inscriptions drafted in a suitably olde-worlde literary style. And if one intruded on the pious hush of a mediaeval scriptorum, one would, it seems, quite likely find the brothers meticulously forging a royal writ with a view to acquiring for the monastery some juicy vineyard here or fat meadow there.

These faker-scholars achieved true greatness in the person of Annius, the 15th-century Italian Dominican who coun- terfeited and buried a series of inscriptions calculated to glorify his home town of Viterbo, and when they were discovered and unearthed, wrote learned commentar- ies on them. Annius thus not only became the father of modern epigraphy but also, by laying down sound 'rules of historical evidence' (drawn from a spurious antique text of his own concoction, but none the worse for that), introduced more rigorous procedures for the study of history. And so down the centuries the will to create fakes and the passion for unmasking them have acted as a spur to scholarly endeavour.

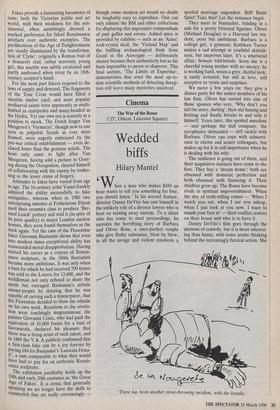

'Clytie', before and after: A Roman bust from the Sir John Soane's Museum (right) and a similar antique piece recut in the 18th century to suit contemporary taste. Fakes provide a fascinating barometer of taste: both the Victorian public and art world, with their weakness for the sen- timental, often unwittingly showed a marked preference for faked Renaissance artefacts over authentic examples. The predilections of the Age of Enlightenment are vividly illuminated by the transforma- tion of 'Clytie': originally a Roman bust of a demurely clad, rather matronly young girl, this marble was subtly eroticised and partly undressed when recut by an 18th- century sculptor's hand.

For the most part fakers respond to the laws of supply and demand. The fragments of the True Cross would have filled a sizeable timber yard, and most popular mediaeval saints were apparently as multi- limbed as centipedes and many-headed as the Hydra. Yet our own era is scarcely in a position to mock. The Dutch forger Van Meegeren's `Vermeers', though now to our eyes as palpable frauds as ever were framed, were eagerly embraced by the pre-war critical establishment — even de- clared better than the genuine article. The hoax only came to light after Van Meegeren, having sold a picture to Goer- ing during the Occupation, cleared himself of collaborating with the enemy by confes- sing to the lesser crime of forgery.

Attitudes to fakes have varied from age to age. The 16-century artist Vasari frankly admired the ability successfully to fake antiquities, whereas when in 1980 two enterprising inmates at Fetherstone Prison used their ceramics class to produce 'Ber- nard Leach' pottery and sold it (in spite of its poor quality) to major London auction houses, they soon found themselves in the dock again. Yet the case of the Florentine faker Giovanni Bastianini shows that even into modern times exceptional ability has transcended moral disapprobation. Having started his career as a copyist of Renais- sance sculpture, in the 1860s Bastianini became more ambitious. It was only when a bust for which he had received 700 francs Was sold to the Louvre for 13,600, and the middleman not only refused to share the spoils but outraged Bastianini's artistic amour-propre by denying that he was capable of carving such a masterpiece, that the Florentine decided to blow the whistle on his own work. Reactions to the revela- tion were touchingly magnanimous: the painter Giovanni Costa, who had paid the equivalent of 10,000 francs for a bust of Savonarola, declared his pleasure that a there was living artist of such talent, and in 1869 the V & A publicly confirmed that a first-class fake can be a joy forever by paying £84 for Bastianini's `Lucretia Dona- te, a sum comparable to what they would have had to pay for an authentic Renais- sance sculpture. The exhibition justifiably holds up the 19th and early 20th centuries as `the Great Age of Fakes'. It is ironic that generally speaking we no longer have the skills to counterfeit fine art really convincingly — though some modern art would no doubt be laughably easy to reproduce. One can only admire the BM and other collections for displaying this impressive compendium of past gaffes and errors. Added spice is provided by exhibits — such as an 'Aztec' rock-crystal skull, the 'Vinland Map' and the baffling archaeological finds from Gozel in the Auvergne — deliberately chosen because their authenticity has so far been impossible to prove or disprove. This final section, 'The Limits of Expertise', demonstrates that even the most up-to- date scientific methods of detecting decep- tion still leave many mysteries unsolved.

Previous page

Previous page