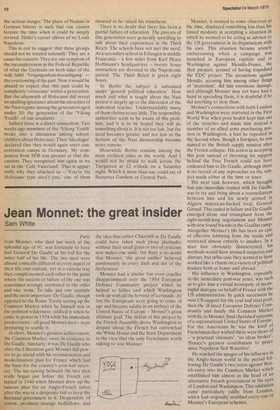

Jean Monnet: the great insider

Sam White

Paris Jean Monnet, who died last week at the splendid age of 91, was fortunate to have had General De Gaulle as his foil for the latter half of his life. The two men were almost comically different in every aspect of their life and outlook, yet in a curious way they complemented each other to the point where the success or failure of the one was sometimes wrongly attributed to the other and vice versa. To take just one example and the most important: De Gaulle, though opposed to the Rome Treaty setting up the Common Market when he himself was in the political wilderness, ratified it when he came to power in 1958 while his immediate predecessors– all good Monnet men – were preparing to scuttle it.

In short, Monnet's greatest achievement, the Common Market, owes its existence to De Gaulle. Similarly, it was De Gaulle who after the Liberation gave Monnet full powers to go ahead with his reconstruction and modernisation plan for France which laid the basis for the country's post-war recovery. The see-sawing between the two men really began just before the French collapsed in 1940 when Monnet drew up the famous plan for an Anglo-French union after the war in a desperate bid to keep the Reynaud government in it. Desperation, of course, produces strange bedfellows, and the idea that either Churchill or De Gaulle could have taken such pious platitudes without their usual grain or two of cynicism now makes one smile, but there is no doubt that Monnet, 'the great unifier' believed passionately in every dash and dot of the declaration.

Monnet had a similar but even crueller disappointment over the 1954 European Defence Community project which he helped to father and which Washington took up with all the fervour of a crusade. At last the Europeans were going to come of age and become adults in an embryo of the United States of Europe – Monnet's great ultimate goal. The defeat of this project by the French Assembly drove Washington to despair about the French but entrenched the White House and the State Department in the view that the only Frenchman worth talking to was Monnet. Monnet, it seemed to some observers at the time, displayed something less than his famed modesty in accepting a situation in which he seemed to be acting as advisor to the US government in its disputations with his own. This situation became acutely embarrassing when a campaign was launched in European capitals and in Washington against Mendes-France, the then premier, accused of having torpedoed the EDC project. The accusations against Mendes, accusing him among other things of 'neutralism', did him enormous damage, and although Monnet may not have had a hand in spreading them, it is doubtful if he did anything to stop them. Monnet's connections with both London and Washington were nurtured in the First World War when poor health kept him out of the trenches and made him instead a member of an allied arms purchasing mission in Washington, a feat he repeated in the Second when, though a foreigner, he was named to the British supply mission after the French collapse. His action in accepting this post instead of throwing his support behind the Free French could not have endeared him to De Gaulle, although there is no record of any reproaches on the subject made either at the time or since. His next task however, which brought him into immediate contact with De Gaulle, was to try and bring about a reconciliation between him and his newly arrived in Algiers American-backed rival, General Giraud. This ended in failure and De Gaulle emerged alone and triumphant from the eight-month-long negotiations and Monnet with new found friends in the Gaullist camp.

Altogether Monnet's life has been an epic of effective lobbying from the inside and restricted almost entirely to insiders. In a man less obviously disinterested, his methods would have aroused suspicion and distrust, but inihis case they seemed to have worked like a charm on a variety of political leaders both at home and abroad.

His influence in Washington, especially in the immediate post-war years, was such as to give him a virtual monopoly of mean ingful dialogue on behalf of France with the US administration. In quick succession he won US support for the coal and steel pool, then the ill-fated European Defence Community and finally the Common Market with its, to Monnet, final cherished outcome of a supranational United States of Europe. For the Americans he was the kind of Frenchman they wished there were more of – 'a practical visionary', 'an ideas broker, 'France's greatest contribution to peace since Napoleon fled Waterloo'. He reached the apogee of his influence in the Anglo-Saxon world in the period fol lowing De Gaulle's two vetos against Brit ish entry into the Common Market which established him almost as the head of an alternative French government in the eyes of London and Washington. This adulation came particularly oddly from London, which had originally snubbed every one of Monnet's European schemes.

Previous page

Previous page