Angry Young Men look back

Lindsay Anderson

THE HONOURABLE BEAST: A POSTHUMOUS AUTOBIOGRAPHY by John Dexter Nick Hem Books, £25, pp. 340 Surely we, the 'Angry Young Men' of the Royal Court Theatre 30-odd years ago, were a remarkable bunch. Certainly we

were very lucky. George Devine, our unique leader, was at the head of it; and with extraordinary prescience he chose Tony Richardson to be his associate. As their assistants there were John Dexter, Bill Gaskill and myself. Anthony Page and Peter Gill joined a little later. Jocelyn Her- bert was painting scenery in the workshops before she started designing. Alan Tagg did many of the early sets. Joan Plowright, Robert Stephens, Frank Finlay and Alan Bates were junior members of the company. John Osborne acted and wrote plays.

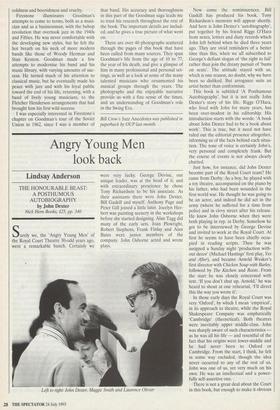

Left to right: John Dexter, Maggie Smith and Laurence Olivier Now come the reminiscences. Bill Gaskill has produced his book. Tony Richardson's memoirs will appear shortly. And here is John Dexter's 'autobiography', put together by his friend Riggs O'Hara from notes, letters and diary records which John left behind when he died three years ago. They are vivid reminders of a better time than this, when we all subscribed to George's defiant slogan of 'the right to fail' rather than join the dreary pursuit of 'bums on seats'. The attitude stayed with us, which is one reason, no doubt, why we have been so disliked. But arrogance suits an artist better than conformism.

This book is subtitled 'A Posthumous Autobiography', but it is not really John Dexter's story of his life. Riggs O'Hara, who lived with John for many years, has been over-modest in his editorship. His introduction starts with the words: 'A book about John Dexter had to be a book about work'. This is true, but it need not have ruled out the editorial presence altogether, informing us of the facts behind each situa- tion. The tone of voice is certainly John's, very personal and completely frank. But the course of events is not always clearly charted.

Just how, for instance, did John Dexter become part of the Royal Court team? He came from Derby. As a boy, he played with a toy theatre, accompanied on the piano by his father, who had been wounded in the first world war. He thought he was going to be an actor, and indeed he did act in the army (where he suffered for a time from polio) and in civvy street after his release. He knew John Osborne when they were both playing in rep. in Derby. Somehow he got to be interviewed by George Devine and invited to work at the Royal Court. At first he seems to have been chiefly occu- pied in reading scripts. Then he was assigned a Sunday night 'production with- out decor' (Michael Hastings' first play, Yes and After), and became Arnold Wesker's first director with Chicken Soup with Barley, followed by The Kitchen and Roots. From the start he was closely concerned with text. 'If you don't shut up, Arnold,' he was heard to shout at one rehearsal, 'I'll direct this the way you wrote it'.

In those early days the Royal Court was very 'Oxford', by which I mean 'empirical', in its approach to theatre, while the Royal Shakespeare Company was emphatically `Cambridge' (theoretical). Both theatres were inevitably upper middle-class. John was sharply aware of such characteristics as he was all his life — and resentful of the fact that his origins were lower-middle and he had never been to Oxford or Cambridge. From the start, I think, he felt in some way excluded, though the idea never occurred to any of the rest of us. John was one of us, yet very much on his own. He was an intellectual and a power- fully self-assertive one.

There is not a great deal about the Court in this book, but enough to make it obvious

that the experience of Sloane Square was for John Dexter, as it was for all of us, both liberating and formative. George Devine, whom John well described as 'the only man I know who could help without interfering', was a key, paternal figure; and the impor- tance of Jocelyn Herbert (`the designer who has always guided my best work') is very clear. It is not explained, though, how Laurence Olivier, struggling to crew his National Theatre in the late Fifties, got John and his friend and colleague William Gaskill to join him at the Old Vic. This anyway is how, in 1963, John directed Joan Plowright as St Joan and the next year Olivier as Othello, with decor and cos- tumes by Jocelyn Herbert.

The National brought John Dexter together with Peter Shaffer for the first time, for his spectacular Royal Hunt of the Sun. Other new plays followed: Arden's Armstrong's Last Goodnight (co-directed with Bill Gaskill), Shaffer's Black Comedy and Osborne's A Bond Honoured. Then he was sacked. Was this because Laurence Olivier, always ambivalent about John's homosexuality, regarded him with suspi- clan? We are left to guess. But after direct- ing his first film, The Virgin Soldiers (not exactly a success), John returned to the National for A Woman Killed with Kindness. Then more Wesker at the Court. He had always loved and understood music: with Berlioz and Verdi he started to direct opera, at Covent Garden and Hamburg.

It was a strenuous, intense and varied career. Perhaps this caused Dexter to be looked at askance in his own country, where artists are preferably respectable (his homosexuality and outspokenness deprived him and deprived Chichester of the possibility of his directing the theatre festival there). And in England one is sup- posed to stick to what one has been seen to do well. So it was somehow inevitable that in 1974 John should be invited to become Director of Productions at New York's Metropolitan Opera. He accepted. But it was probably also inevitable that seven years later conflict with the management and particularly with the Musical Director James Levine, just as wilful as John, should lead to his dismissal.

Mozart, Weill, Verdi, Berg, Satie, Ravel and Stravinski were among John Dexter's composers at the Met. His productions had been designed by Jocelyn Herbert, Svobo- da, Bill Dudley and David Hockney among others. It was a record he could be proud of. And when one remembers that during this operatic career, he found time also for theatre productions like Pygmalion and Phaedra Britannicus, As You Like It and Galileo at the National, one can see how he thrived on activity. Neither ill-health, of which he had more than his share, nor opposition seemed ever to make him pause.

The title of this book came to Riggs O'Hara when he remembered John calling his godson, who was always late, 'a beast'.

`You're a beast too,' said Riggs, truthfully, tut an honourable one'. Perhaps this meant that John's beastliness was always or so he would claim — in the name of principle. I am not quite sure about this. Although he soon dismissed his early ambi- tion to be an actor, there was something histrionic about his personality as a collab- orator and as a director. John enjoyed demonstrating his authority in rehearsal, which too often meant unkindness to one member at least of his cast. Though himself strongly emotional, he seemed scared of emotion, of sentiment. His judgment of character and relationship could sometimes be criticised, though never his sense of mise-en-scene. He was always an outstand- ing theatrical director, with a brilliant sense of staging — as witness the disciplined choreography of The Kitchen, the crossing of the Andes in The Royal Hunt, the whole conception of Equus, which was largely responsible for the play's world-wide success. Such tours-de-force were always more striking than the emotional truth of John's work.

Perhaps this is the reason why so many of his collaborative plans came to nothing. After the Met., John tried many times to form a company of his own, to perpetuate a style. But his production of The Glass Menagerie in New York, which should have started things off, was not a success. Back in London, he talked to Peter Hall about the possibility of their assuming joint responsibility, each with his own company, for the Olivier and the Cottesloe at the National Theatre; but in the end the appointment went to Peter Gill (and John commented bitterly that he was left to find this out by reading the announcement in the Press). He was a loner as well as an egoist, which always made collaborations difficult. What this book makes very clear is his consistency of aim and his refusal to compromise. He was often uncomfortably frank and always impatient with anything he considered second-rate. No wonder the Royal Court rejected him, like Chich- ester. His diary entry for 4 August 1986 read: 'Hang out the Flags for the New Theatre Company this week'. Unhappily, the breeze did not blow and the flags did not flutter.

John Dexter died in 1990, prematurely (he was born in 1925) and unexpectedly (his heart operation was judged a minor one, not risky). He was still full of plans: Alec McCowen as Othello, Joan Plowright as Cleopatra. He was excited at the prospect of working with Tariq Ali and Howard Brenton on their satire Moscow Gold. Ten days before he died he had noted, 'Consider Jacobi, Thaw, Woodward, Finney. Phone R.S.C. re. their list of "stars" '. The flow of ideas never dried up. Some of them would have come to nothing, but some would have materialised, to jolt, disappoint or stimulate. To lose and to win. No one has replaced John. No one could. This book explains why.

Previous page

Previous page