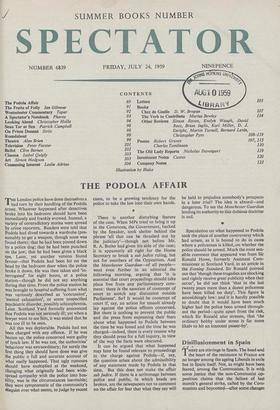

THE PODOLA AFFAIR

THE London police have done themselves a bad turn by their handling of the Podola arrest. Whatever happened after detectives broke into his bedroom should have been immediately and frankly avowed. Instead, a variety of contradictory stories were spread by crime reporters. Readers were told that Podola had dived towards a wardrobe (pre- sumably to get a weapon, though none was found there); that he had been pinned down by a police dog; that he had been punched on the jaw; that he had been given a black eye. Later, yet another version found favour—that Podola had been hit on the head by the bedroom door when the police broke it down. He was then taken and 'in- terrogated' for eight hours, at a police station—though he did not say anything during that time. From the police station he was brought to hospital suffering from what Was variously described as 'concussion', 'mental exhaustion', or some unspecified Psychiatric disorder, possibly schizophrenia. Later. Scotland Yard formally announced that Podola was not seriously ill; yet when a lawyer went to see him, it was stated that he Was too ill to be sect).

All this was deplorable. Podola had not been charged with any offence. If he was beaten up, the police concerned were guilty of lynch law. If he was not, the authorities' behaviour was extraordinary; for surely the first thing they should have done was give the public a full and accurate account of What really happened. That ugly rumours Should have multiplied at the weekend, changing what originally had been wide- spread sympathy with the police into hos- tility, was in the circumstances inevitable; they were symptomatic of the community's disquiet over what seems, to judge by recent cases, to be a growing tendency for the police to take the law into their own hands.

There is another disturbing feature of the case. When MPs tried to bring it up in the Commons, the Government, backed by the Speaker, took shelter behind the phrase 'all that can be thrashed out by the judiciary'—though not before Mr. R. A. Butler had given his side of the case; it is apparently all right for the Home Secretary to break a sub judice ruling, but not for members of the Opposition. And the Manchester Guardian—of all people— went even further in an editorial the following morning, arguing that 'it is essential that court proceedings should take place free from any parliamentary com- ment: there is the sanction of contempt of court to scotch any discussion outside Parliament'. So? It would be contempt of court if, say, an action for assault already lay against the police officers concerned. But there is nothing to prevent the public and the press from expressing their fears about what happened to Podola between the time he was found and the time he was charged—indeed, there is every reason why they should press for a full inquiry, in view of the way the facts were obscured.

It can be argued that what happened may later be found relevant to proceedings in the charge against Podola—if, say, the question arises about the admissibility of any statement made by Podola in that time. But this does not make the affair sub judice. If there is a scrimmage between police and public, in which heads are broken, are the newspapers not to comment on the affair for fear that what they say will be held to prejudice somebody's prospects in a later trial? The idea is absurd—and dangerous. To see the Manchester Guardian lending its authority to this dubious doctrine is sad.

Speculation on what happened to Podola took the place of another controversy which had arisen, as it is bound to do in cases where a policeman is killed,.on whether the police should be armed. Much the most sen- sible comment that appeared was from Sir Ronald Howe, formerly Assistant Com- missioner at Scotland Yard, in an article in the Evening Standard. Sir Ronald pointed out that 'though these tragedies are shocking and rightly receive great publicity when they occur', he did not think 'that in the last twenty years more than a dozen policemen have been killed on duty'. This figure is astonishingly low: and it is hardly possible to doubt that it would have been much higher had the police been armed through- out the period—quite apart from the risk, which Sir Ronald also stresses, that 'the ordinary bobby under stress is far more likely to hit an innocent passer-by'.