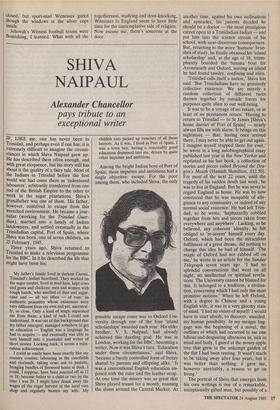

SHIVA NAIPAUL

Alexander Chancellor pays tribute to an exceptional writer

IF, LIKE me, one has never been to Trinidad, and perhaps even if one has, it is extremely difficult to imagine the circum- stances in which Shiva Naipaul grew up. He has described them often enough, and With great eloquence, but his story still has about it the quality of a fairy tale. Most of the Indians in Trinidad before the first world war had come there as 'indentured labourers', arbitrarily transferred from one end of the British Empire to the other to Work in the sugar plantations. Shiva's grandfather was one of them. His father, however, contrived to escape from this wretched environment. He became a jour- nalist (working for the Trinidad Guar- dian), married into a family of Indian landowners, and settled eventually in the Trinidadian capital, Port of Spain, where Shiva was born, one of seven children, on 25 February, 1945.

Three years ago, Shiva returned to Trinidad to make a television programme for the BBC. In it he described the life that might have been his: My father's family lived in darkest Caroni, Trinidad's Indian heartland. They worked on the sugar estates, lived in mud huts, kept cows and goats and chickens: men and women with rough hands, who smelled of dust and sugar- cane and — all too often — of rum: an authentic peasantry whose existences were very different from my own and yet, ancestral- ly, so close. Only a kind of magic separated me from them; a kind of luck I could not understand. It was out of this background that my father emerged, managed somehow to get an education — English was a language he had to acquire — and eventually was able to turn himself into a journalist and writer of short stories. Looking back, it seems a mira- culous achievement.

I could so easily have been exactly like my country cousins: labouring in the canefields and ricelands, taking cows out to pasture, bringing bundles of firewood home at dusk. I could, I suppose, have been married off at 17 or 18; become father to a child or two by the time I was 20. I might have drunk away the wages of the sugar harvest in the local rum Shop and regularly beaten my wife. My childish ears picked up rumours of all these horrors. As it was, I lived in Port of Spain. I was a town boy, having a reasonably good education drummed into me, driven by quite other impulses and ambitions.

Among the bright Indian boys of Port of Spain, these impulses and ambitions had a single objective: escape. For the poor among them, who included Shiva, the only possible escape route was to Oxford Uni- versity through one of the four 'island scholarships' awarded each year. His elder brother, V. S. Naipaul, had already achieved this dazzling goal. He was in London, working for the BBC, becoming a writer. Now it was Shiva's turn. 'Education under these circumstances,' said Shiva, 'became a barely controlled form of frenzy shared by parents and offspring alike.' It was a conventional English education im- posed with the ruler and the leather strap. At one time the misery was so great that Shiva played truant for a month, roaming the slums around the Central Market. At another time, against his own inclinations and aptitudes, his parents decided he should be a doctor — the most prestigious career open to a Trinidadian Indian — and put him into the science stream of his school, with near-disastrous consequences. But, returning to the more 'humane' bran- ches of study, he finally obtained his 'island scholarship' and, at the age of 18, trium- phantly boarded the banana boat for Avonmouth and Oxford, leaving an island he had found tawdry, confining and alien.

'Trinidad calls itself a nation,' Shiva has said. 'But Trinidadians have no genuinely collective existence. We are merely a random collection of different races thrown together by outside forces for purposes quite alien to our well-being.'

It was to be a voyage of no return, or at least of no permanent return. 'Having to return to Trinidad — to St James [Shiva's home district of Port of Spain] — nearly always fills me with alarm. It brings on this nightmare — that, having once arrived there, I may never be able to get out again. I imagine myself trapped there for ever,' he wrote in a long autobiographical essay published last year in the New Yorker and reprinted in his last book, a collection of stories and pieces called Beyond the Dra- gon's Mouth (Hamish Hamilton, L12.50). For most of the next 22 years, until the tragedy of his sudden death last week, he was to live in England. But he was never to regard England as home. He was by now convinced that he was incapable of alle- giance to any community, or indeed of any normal social existence. He had left Trini- dad, so he wrote, 'haphazardly cobbled together from bits and pieces taken from everywhere and anywhere'. Lacking, so he believed, any coherent identity, he felt obliged to 're-invent' himself every day. Oxford, which had been the miraculous fulfilment of a great dream, did nothing to change this idea he had of himself. 'The magic of Oxford had not rubbed off on me,' he wrote in an article for the Sunday Telegraph seven years ago. 'I had no splendid conversations that went on all night, no intellectual or spiritual revela- tions. The University cannot be blamed for this. It belonged to a tradition, a civilisa- tion, concerning which I had only the most primitive notions.' When he left Oxford, with a degree in Chinese and a young English wife, it was in a very gloomy state of mind. 'I had no vision of myself: I would have to start afresh; to discover, unaided, my human possibility. In my meagre bag- gage was the beginning of a novel, the outlines of which had occurred to me one bilious and despairing afternoon as, sick in mind and body, I gazed at the mossy apple tree that grew in the unkempt garden of the flat I had been renting. It wasn't much to be taking away after four years, but it was better than nothing: it gave me, however unreliably, a reason to go on living.'

The portrait of Shiva that emerges from his own writings is one of a remarkable, exceptionally gifted man, but possibly of a man one would not care to know, of a solitary, gloomy, self-obsessed person, lacking the gift of companionship. It is a portrait in this last respect so misleading that it fairly takes the breath away.

What keeps coming back to me at the moment is his laugh: high, rasping and infectious. Writing may have been his main 'reason to go on living' — indeed, I believe that it was — but he was one of the most companionable people I have ever met. The headline over Martin Amis's apprecia- tion of him in last Sunday's Observer was 'A talent for warmth'. It was exactly the right headline, because it was — to those who did not know him — the most improb- able of Shiva's qualities.

I first met him about ten years ago after he had already written two prize-winning novels, both set in Trinidad: Fireflies (1970), and The Chip-Chip Gatherers (1973). I had read neither of them. Indeed, I knew very little about him. I had just been appointed editor of the Spectator and had advertised for a secretary. I inter- viewed about 30 candidates, but one was quite obviously much better qualified, much more intelligent, and very much nicer than any of the others. She turned out to be Shiva's wife, Jenny. Jenny quickly became far more than a secretary, though she was brilliant in that role. She became (and still is) an indispensable member of the editorial staff, the person with whom our contributors most liked to communicate. I was sometimes quite jealous of her in this respect. I was even more jealous of Shiva. However petty his needs might have seemed in comparison with mine, he always came first. Working for an island scholarship' is clearly a full-time occupation. So far as I could tell, Shiva had failed to master even the most elementary of practical skills. He couldn't boil an egg or mend a fuse. If a tap was dripping, so to speak, he would telephone Jenny at the office and she would rush home immediately to deal with it. She would deal with everything. He couldn't possibly have coped without her. If, in his literary persona, he tended to ignore her existence, his dependence on her was nevertheless absolute.

One of the things Jenny did was to introduce Shiva to the Spectator. More than half the non-fictional pieces in Beyond the Dragon's Mouth were first published in this paper, as were parts of his 1978 African travel book North of South. These articles were, without exception, excellent. As a writer dedicated to his craft, he devoted much more time to them than most journalists do. He refused to be rushed. He would only deliver his pieces when he felt they were right. He brought to them not only his rare skills as a writer and his novelist's powers of observation, but an independence of mind which came from his own sense of belonging nowhere. One might be tempted to call it detachment, but that would not be right. He minded very much about things and about people. What he minded most of all was the way in which

fools and bigots would misrepresent real- ity. He was a genuine seeker after truth.

But the main thing now is to recall those qualities which he seemed not to realise he possessed — warmth, good humour, and an exceptional capacity for friendship. He was much too obsessed with his lack of 'a collective consciousness'. It made him think he was much unhappier than he was. I believe he had recently become quite happy, with his large and comfortable new flat in Hampstead, with his growing success as an author, with his circle of devoted friends — not to mention his extraordinary good fortune in his wife and son, Tarun. Had he lived, he would not only have written more marvellous books; he would soon have been ready to call England his home. Or so I believe. His death was an appalling tragedy. His loss is even harder to understand than his extraordinary life.

Previous page

Previous page