WITNESS AT THE DOOR

Roy Kerridge watches

Jehovah's Witnesses being baptised by total immersion

Twickenham WHETHER you are enjoying a bath, anxiously waiting for a loved one to call or trying to write an article for the Spectator, a visit from the Jehovah's Witnesses can only bring rage, grief or disappointment. Polite to a fault, the Witnesses are easily got rid of. If you are polite in return and ask them in, you will lay the foundation for incessant future visits. In the end you must either rebuff them or succumb to their message. What does it feel like to be a Witness, on the other side of the door?

'How are we to know when it's conve- nient to call?' one of them asked me pathetically. 'Some people don't get up till noon, others have meals at varying times. We have no desire to irritate people, but we do feel we have an urgent message, as the end is near.'

From 25 to 28 July, the Jehovah's Witnesses of south-east England gathered at Twickenham rugby ground for their Annual District Convention. There must have been 30,000 present, for every seat in the vast stadium was filled, tier upon tier, and Witnesses strolled around the concrete perimeter of the pitch, where zigzag steps led up to the towering height of sky- scraping stalls. Near one of the entrances, a statue of a lion stood rampant on a pillar, and all around were stalls selling food and shops selling books such as Reasoning from the Scriptures. This volume attempts snap- py answers to householders who slam doors with cries of 'I'm busy!', 'I'm a Buddhist!', or perhaps 'I'm a busy Buddh- ist!' Social workers have similar manuals, with suggested 'bright remarks', but they are able to assume a mantle of menace, unlike the far more innocent Witnesses.

Once the tables were turned, and I had called on the Witnesses, they seemed a mild, contented people, very eager to please. You could not possibly dislike them. As not everyone is called to be a Witness, homes can be broken up by a knock at the door, but at Twickenham all I saw were happy families. Despite their belief that only 144,000 souls can enter heaven, Witnesses seem very much like fundamentalist Christians. In some ways they are less strict, as girls are allowed to wear make-up. West Indian and white Witnesses seemed very much at ease with one another. Nationalities and earthly powers are not recognised by Witnesses who do not vote or take part in politics. Everyone was well dressed and well groomed, and the children, denied birth- day and Christmas presents, seemed merry enough. Heaven may be exclusive, but Witnesses expect a paradise on earth, one resembling a National Park picnic area in the Rockies, to judge from the illustrations in Watchtower magazine.

In Jehovah's Witness chapels, known as Kingdom Halls, the articles in the Watch- tower are examined minutely, sentence by sentence, during services of enor- mous tedium to those 'outside the Truth'. Rolls of food tokens, at five pence a ticket, had been bought by the Convention-goers beforehand, for none of the vendors was allowed to handle money. A kindly Wit- ness, Mrs Pople, served me a free meal. On Saturday morning I hurried through the throng, among West Indian women who shrilled a 'ha ha ha-haaa!' greeting to one another, and made my way to a roped-off area where the mass baptisms were to take place.

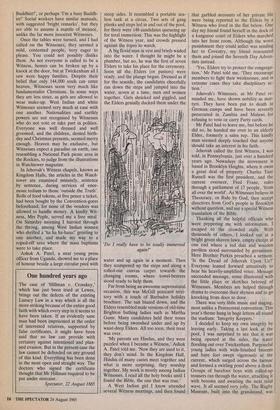

Ashok A. Patel, a neat young press officer from Uganda, showed me to a place of honour beside a large circular pool with steep sides. It resembled a portable sea- lion tank at a circus. Two sets of gang planks and steps led in and out of the pool, for there were 148 candidates queueing up for total immersion. This was the highlight of the Witness year, and crowds pressed against the ropes to watch.

A big florid man in vest and briefs waded into the water. I thought he might be a plumber, but no, he was the first of seven Elders to take his place for the ceremony. Soon all the Elders (or pastors) were ready, and the plunge began. Dressed as if for the seaside, the candidates cheerfully ran down the steps and jumped into the water, seven at a time, men and women together. Girls shrieked and giggled, and the Elders genial y ducked them under the 'Do I really have to be totally immersed again?'

water and up again in a moment. Then they scampered up the steps and along a rolled-out canvas carpet towards the changing rooms, where towel-bearers stood ready to help them.

Far from being an awesome supernatural occasion, this was McGill postcard terri- tory with a touch of Barbados holiday brochure. The sun blazed down, and the Elders resembled male versions of old-time Brighton bathing ladies such as Martha Gunn. Many candidates held their noses before being swooshed under and up by waist-deep Elders. All too soon, their treat was over.

'My parents are Hindus, and they were puzzled when I became a Witness,' Ashok A. Patel told me. 'Now they are used to it, they don't mind. In the Kingdom Hall, Hindus of many castes meet together and what is more surprising, they worship together. My work is mostly among Indian Witnesses. I read all the holy books until I found the Bible, the one that was true.'

A West Indian girl I know attended several Witness meetings, and then found that garbled accounts of her private life were being reported to the Elders by a Witness who lived in the flat below. One day my friend found herself in the dock of a kangaroo court of Elders who marched into her front room. Although the worst punishment they could inflict was sending her to Coventry, my friend renounced them and joined the Seventh Day Adven- tists instead.

'Yes, Elders try to protect the congrega- tion,' Mr Patel told me. 'They encourage members to fight their weaknesses, and in extreme cases they take disciplinary ac- tion.'

Jehovah's Witnesses, as Mr Patel re- minded me, have shown nobility as mar- tyrs. They have been put to death in German camps and have been severely persecuted in Zambia and Malawi for refusing to vote or carry Party cards.

Mr Patel had to leave me, but before he did so, he handed me over to an elderly Elder, formerly a sales rep. This kindly man seemed deeply touched that anyone should take an interest in his faith.

Jehovah called the first Witness, I was told, in Pennsylvania, just over a hundred years ago. Nowadays the movement is based in Brooklyn Heights, where it owns a great deal of property. Charles Taze Russell was the first president, and the current overseer, Fred Franz, rules through a parliament of 17 people, 'from all over the world'. As Witnesses believe in Theocracy, or Rule by God, they accept directives from God's people in Brooklyn without question, and use a special Witness translation of the Bible.

Thanking all the helpful officials who were peppering me with information, I escaped to the crowded stalls. With thousands of others, I looked out at a bright green shaven lawn, empty except at one end where a red dais and wooden pavilion stood surrounded by geraniums. Here Brother Parkin preached a sermon: 'Is the Dread of Jehovah Upon Us?' Everyone leaned forward attentively to hear his heavily-amplified voice. Message succeeded message, some illustrated with the little plays or sketches beloved of Witnesses. Members are helped through drama to overcome their shyness and to go knocking from door to door.

There was very little music and singing, most unlike a Pentecostal convention. This year's theme hung in huge letters all round the stadium: 'Integrity Keepers.'

I decided to keep my own integrity by leaving early. Taking a last look at the pool, I was surprised to see that it was being opened at the sides, the water flooding out over Twickenham. Purposeful young ladies with wide-brushed brooms and bare feet swept vigorously at the current, which surged across the tarmac and formed a swirling pond above a drain. Groups of barefoot boys with rolled-up trousers ran through the water, attacking it with brooms and awaiting the next tidal wave. It all seemed very jolly. The Rugby Museum, built into the grandstand, was closed, but sport-mad Witnesses gazed though the windows at the silver cups Inside.

Jehovah's Witness football teams were flourishing, I learned. What with all the togetherness, studying and door-knocking, Witnesses in England seem to have little time for the contemplative side of religion. Now excuse me, there's someone at the door.

Previous page

Previous page