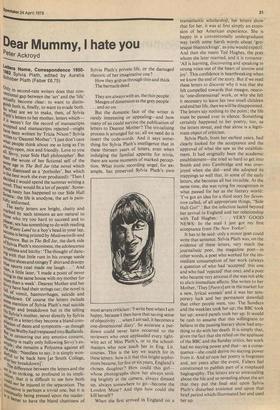

bear Mummy, I hate you

Peter Ackroyd Letters Home, Correspondence 1950s3 Sylvia Plath, edited by Aurelia Chober Plath (Faber £6.75) Only in second-rate writers does that conventional gap between the 'art' and the 'life' aetuallY become clear: to want to distintish both is, finally, to want to evade both. II° what are we to make, then, of Sylvia ifla.th's letters to her mother, letters which— Weren't for the record of manuscripts 4becepted and manuscripts rejected—might aVe been written by Tricia Nixon? Sylvia Writes to 'Dearest Mother': 'I just don't care :villat People think about me as long as l'm all ''%vaYs open, nice and friendly. Love to you Sivvy, your Side Hall philosopher'. But "en she wrote of her fictional self of the spline age in The Bell Jar (the novel which i 'alb dismissed as a 'potboiler', but which d3 the best work she ever produced): 'Then 1 „eeided I would spend the summer writing a That would fix a lot of people'. Somesneing nasty has happened to our Side Hall f,neca: the life is anodyne, the art is pain'nlY unformed.

early letters are bright, chatty and "1arked by such tensions as are natural to l,., ;cise who try too hard to succeed and to 'pease; sex has something to do with reading Waste Land to a boy's head in your lap, 'success is being printed by Mademoiselle and oreventeen. But in The Bell Jar, the dark side is SYivia Plath's mooniness, the adolescence inruthless and bitchy: `The thought of clanceig vvith that little runt in his orange suede bievator shoes and mi ngey T shirt and droopy

sPorts coat made me laugh . ' And

a little later, '1 made a point of never In g11 the same house with my mother for siure than a week'. Dearest Mother and her

vY have had their strings cut; the novel is

1 of vomit, haemorrhages, suicide and kdown. Of course the letters include ktirne mention of Sylvia Plath's real suicide (benlPt and breakdown but in the telling heY SYlvia's mother, never directly by Sylvia :seir in a letter) they become a bland cornki:tion of dates and symptoms—as though qrcusWel by had trespassed into Badlands. in censoring out any emotive content, anillhin, MY is really only following Sivvy's exth vie; she remains a Polyanna against all d: odds: 'Needless to say, it is simply wonaftrftd to be back here [at Smith College, Ter,her breakdown]'. 4ri :le difference between the letters and the ciktils so striking, so profound in its implie01:13111. that it is difficult to see how both alt:'d nor be injured in the separation. The oriv4rlative is perhaps a trivial one, but it is is uallY being pressed upon the reader: ' oetter to have the bland chattiness of

Sylvia Plath's private life, or the damaged rhetoric of her imaginative one?

How they grip us through thin and thick The barnacle dead They are always with us, the thin people Meagre of dimension as the grey people ... and so on.

But the domestic face of the writer is rarely interesting or appealing—and how many of us could survive the publication of letters to Dearest Mother? The trivialising process is arranged for us; all we need do is insert the code-words. And it says something for Sylvia Plath's intelligence that in these thirteen years of letters, even when indulging the familial appetite for trivia, there are some moments of marked perception. What ironic recording angel, for example, has preserved Sylvia Plath's own

most severe criticism : 'I write best when l am happy, because I then have that saving sense of objectivity ... when I am sad, it becomes a one-dimensional diary'. So accurate a putdown could never have occurred to the reviewers who once applauded every tightwire act of Miss Plath's, or to the schoolmasters who now teach her in Eng. Lit. courses. This is the key we search for in these letters: how is it that this bright sophomore became, for five or six years, England's chosen daughter? How could this girl— whose photographs show her always smiling brightly at the camera, always dressed up, always somewhere to go—become the London Muse? And then how could she kill herself?

When she first arrived in England on a transatlantic scholarshit3, her letters show • that for her, it was at first simply an extension of her American experience. She is happy in a conventionally undergraduate way (with some harsh words about 'grotesque bluestockings', as you would expect). And then she meets Ted Hughes, the poet whom she later married, and it is romance: 'All is learning, discovering and speaking in strong voice out of the heart of sorrow and joy'. This confidence is heartbreaking when we know the end of the story. But if we read these letters to discover why it was that she felt compelled towards that meagre, neurotic 'one-dimensional' work, or why she felt it necessary to leave her two small children and end her life, then we will be disappointed. The letters say nothing to the point ; the life must be passed over in silence. Something certainly happened to her poetry, too, as the letters reveal, and that alone is a legitimate object of criticism.

Sylvia Plath, from her earliest years, had clearly looked for the acceptance and the approval of what she saw as the establishment. It had originally been the academic establishment—she tried so hard to get into Smith and into Cambridge and was overjoyed when she did—and she adopted its trappings so well that, in some of the early letters, she becomes all but invisible. At the same time, she was vying for recognition in what passed for her as the literary world: 'I've got an idea for a third story for Seventeen called, of all appropriate things, "Side Hall Girl".' But the infection lasted beyond her arrival in England and her relationship with Ted Hughes: '. . . VERY GOOD NEWS: In the mail 1 just got my first acceptance from The New Yorker'.

It has to be said: only a minor p,oet could write that sentence. Sylvia Plath was, on the evidence of these letters, very much the journalistic poet, the magazine poet—in other words, a poet who worked for the immediate consumption of her work (always a question of who had 'accepted' this one and who had 'rejected' that one), and a poet who became very anxious if she was not able to elicit immediate effects. She writes to her Mother, 'They [Poetry]are in the market for a new, lyrical woman' and it was her temporary luck and her permanent downfall that other people were, too. The Sundays and the weeklies took her up; the BBC took her up; award panels took her up. It would be rash to assume that this willingness to believe in the passing literary show had anything to do with her death. It is simply that, given the fact that she relied on the applause of the BBC and the Sunday critics, her work had no staying power and that—as a consequence—she could derive no staying power from it. And so now her poetry is forgotten and, ten years after the event, Fabers feel constrained to publish part of a misplaced hagiography. The letters are so unrevealing about the life and so revealing about the art that they put the final seal upon Sylvia Plath's disturbed existence and upon that brief period which illuminated her and used her up.

Previous page

Previous page