SEEING A WOMAN WITH TUSKS

Paul Webb on the strange life

and imagination of Wilkie Collins, who died 100 years ago

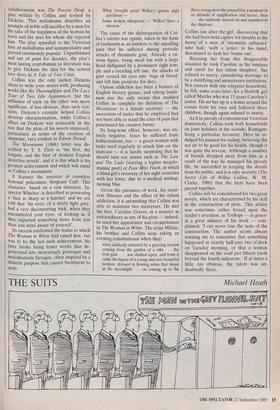

THIS week marks the centenary of the death of William Wilkie Collins, an im- mensely popular novelist (The Woman in White), playwright (The Frozen Deep), and creator of the detective story (The Moon- stone), whose work had a strong influence on that of his friend and contemporary, Charles Dickens, and whose private life was as extraordinary as any of the plots of his thrillers.

Collins was born into an artistic family. His father was a successful painter and RA who named his eldest son after his friend and fellow academician, Sir David Wilkie. His brother, Charles, was to become a minor associate of the Pre-Raphaelites, of whom Millais and Holman Hunt were numbered among Wilkie's closest friends.

Despite these associations and his own talent — he exhibited a landscape at the Royal Academy in 1849 — he was deter- mined to be a writer, having discovered a skill in telling stories at school, where his dormitory prefect refused to let him sleep until he had told him one. A mediocre tale was met with a beating, a good one with a pastry. Writing of this as an adult, Collins noted laconically that 'I learnt to be amusing on a short notice — and have derived benefit from those early lessons.'

His first book was a two-volume biogra- phy of his father, who died in 1847, when Wilkie was 23. The work was one of duty rather than love, Collins senior having been a dour reactionary with a strong religious streak: 'He looked on the Reform Bill and the cholera as similar judgments of an offended deity punishing social and political backsliding.' His career as a short-story writer and novelist blossomed under the patronage and advice of Charles Dickens, with whom he was on the friendliest of terms until towards the end of his life, when Dickens's dislike of his son-in-law (Wilkie's brother) soured their relationship.

The friendship that was to be mutually beneficial to their literary work started at an amateur dramatic performance arranged by Dickens for charity. Both had a strong interest in the theatre, Collins being the more keen. When they travelled on what they referred to as their 'bac- chanalian' jaunts to Paris, Dickens would roam the streets for hours on end, while Collins refused to be lured away from the delights of the French theatres and music halls.

The most successful of their theatrical

collaborations was The Frozen Deep, a play written by Collins and revised by Dickens. This melodrama describes an example of noble self-sacrifice by a man for the sake of the happiness of the woman he loves and the man for whom she rejected him. The play appealed to the Victorian love of melodrama and sentimentality and Proved enormously popular. Unperformed and out of print for decades, the play's most lasting contribution to literature was to give Dickens the idea for the central love story in A Tale of Two Cities.

Collins was the only author Dickens chose to write joint stories with, producing works like No Thoroughfare and The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices, but the influence of each on the other was more significant, if less obvious, than such ven- tures. Dickens's example helped Collins develop characterisation, while Collins's effect on Dickens was noticeable in the way that the plots of his novels improved, Particularly in terms of the creation of suspense, very evident in Edwin Drood. The Moonstone (1868) latter was de- scribed by T. S. Eliot as 'the first, the longest, and the best of modern English detective novels', and it is this which is his greatest achievement and which will stand as Collins's monument.

It features the ancestor of countless fictional policemen, Sergeant Cuff. This character, based on a real detective, In- spector Whicher, is described as possessing a 'face as sharp as a hatchet' and we are told that 'his eyes, of a steely light grey, had a very disconcerting trick, when they encountered your eyes, of looking as if they expected something more from you than you were aware of yourself.

Its success confirmed the status to which The Woman in White had raised him, but was to be the last such achievement, his later books being lesser works that de- generated into increasingly grotesque and melodramatic farragos, often inspired by a didactic purpose that caused Swinburne to quip:

What brought good Wilkie's genius nigh perdition — Some demon whispered — 'Wilkie! have a mission.'

The cause of the disintegration of Col- lins's talents was opium, taken in the form of laudanum as an antidote to the appalling pain that he suffered during periodic attacks of rheumatic gout. Already a cu- rious figure, being small but with a large head disfigured by a prominent right tem- ple and a receding left one, the attacks of gout turned his eyes into 'bags of blood' and left him prostrate for days.

Opium addiction has been a feature of English literary genius, and taking lauda- num was the only means that enabled Collins to complete his dictation of The Moonstone to a female secretary — the succession of males that he employed had not been able to stand the cries of pain that punctuated his creative bursts.

Its long-term effect, however, was en- tirely negative. Since he suffered from hallucinations, too — a green woman with tusks used regularly to attack him on the staircase — it is hardly surprising that he should turn out stories such as The Law and The Lady (starring a legless megalo- maniac poet) or Poor Miss Finch, in which a blind girl's recovery of her sight coincides with her lover, due to a medical mishap, turning blue.

Given the pressures of work, his recur- rent illnesses and the effect of his opium addiction, it is astonishing that Collins was able to maintain two mistresses. He met the first, Caroline Graves, in a manner as extraordinary as any of his plots — indeed, he used her appearance and circumstances in The Woman in White. The artist Millais, his brother and Collins were taking an evening constitutional when they:

were suddenly arrested by a piercing scream coming from the garden of a villa . . . the iron gate . . . was dashed open, and from it came the figure of a young and very beautiful woman, dressed in flowing robes that shone in the moonlight . . . on coming up to the three young men she paused for a moment in an attitude of supplication and terror, then . . she suddenly moved on and vanished in the shadows.

Collins ran after the girl, discovering that she had been held captive for months in the house of a man of 'mesmeric influence' who had, 'with a poker in his hand, threatened to dash her brains out'.

Rescuing her from this disagreeable situation he took Caroline as his mistress and cared for her infant daughter, but refused to marry, considering marriage to be a stultifying and unnecessary institution. Not content with one irregular household, he fell, some years later, for a Norfolk girl called Martha who was 15 years Caroline's junior. He set her up in a house around the corner from his own and fathered three children, though again refused to marry.

As if in parody of conventional Victorian domesticity, Collins took both households on joint holidays at the seaside, Ramsgate being a particular favourite. Here he in- dulged his passion for sailing, believing the sea air to be good for his health, though it was quite the reverse. Although a number of friends dropped away from him as a result of the way he managed his private life, he succeeded in keeping the details from his public, and it is only recently (The Secret Life of Wilkie Collins, W. M. Clarke, 1988) that the facts have been pieced together.

Collins will be remembered for two great novels, which are characterised by his skill in the construction of plots. This ability was sometimes rather forced upon the reader's attention, as Trollope — in gener- al a great admirer of his work — com- plained: 'I can never lose the taste of the construction. The author seems always warning me to remember that something happened at exactly half-past two o'clock on Tuesday morning, or that a woman disappeared on the road just fifteen yards beyond the fourth milestone.' If at times a little too obvious, the talent was un- doubtedly there.

Previous page

Previous page