Portugal: half a counter-revolution

John Biggs-Davison

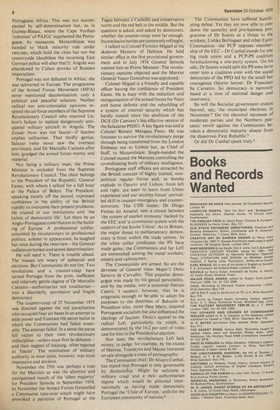

London grows dirtier. Lisbon is filthy. A dead rat lay on the pavement in the shopPing street, Rua do Amparo. This is not . good for tourism and morale. So a start was being made to clean the slogans from the equestrian statue of Pedro IV in the square Where the multi-hued casualities of deColonisation swarm and gossip endlessly, impeding those unlike these driven leaves or the wind of change, who have nowhere to go and no work to do. Yet the once elegant city is still degraded by the vile collage of peeling propaganda of people's power flowing from the barrel of a paint aerosol. Neither Cathedral nor Cenotaph is spared the posters and the slogans.

The Presidential candidates smile toothily and paternally from the posters. Only the victor, General Ramalho Eanes, looks down in uniform, unsmiling, sometimes the effect of the gravitas appropriate to a Head of State marred by the addition to one eye of a monocle—the monocle of General Spin°la, the Kerensky, or rather the Prince Lvov, of the 'Red Carnation Revolution', but now assailed on the Left as a 'fascist assassin'.

General Spinola could not see me, although we had toured Portuguese Guinea together in his helicopter. 'I am a revolutionary', he said in Bissau. Those, however, Who start revolutions never end them. According to Vergiaud in 1791 revolutions devour, like Saturn, all their children.

London and Lisbon—one dirty, the other hltbY. They are capitals of two countries linked in trade and alliance through their successive dynasties and revolutions. Today their formidable problems are the same in kind if not in degree. Great Britain and Portugal have been taken to the edge of anarchy, and in both countries socialist Prime Ministers are summoning the old Market forces and the work ethic of capitalism to reassure lenders and investors at home and abroad and avert collapse, and in this enterprise are endangered from trade union and parliamentary militants.

In England 'Bennery', in Portugal 'adMinistrative commissions' to bolster up the insolvent or unprofitable concern. In both, the evil of unemployment (given as fifteen Per cent in Portugal) is worsened by unwillingness to hire, because it is difficult or forbidden to fire. The industrial workers of both countries live in a transient fool's Puradise of increased wages paid in depreciating currency. The gold that Salazar and ,aetano husbanded is spent or pledged. „now to pay for dearer imports of food and !ceding-stuffs, not to mention the dis?Dearing codfish—the national delicacy? 1.1e nationalisation of Portuguese banks as lost business to foreign competitors.

As in Britain, the cry is for investment. Portuguese employers estimate that in 1975 the gross national product fell by about 12.5 per cent. in real terms. The budget deficit is the worst since 1926, when the First Republic fell. As elsewhere, collectivisation in the Marxist stronghold of the Alentejo, and some parts north of the Tagus, has sown agricultural chaos. In place of the absentee landlord, the bungling bureaucrat.

In Portugal as in Great Britain racism smoulders. Prince Henry the Navigator encouraged intermarriage with Negroes of Guinea. Brazil is, Angola might have been, a Luso-tropical society. Now, however, the immigration of black fugitives from black nationalism and of white or off-white retornados are combustibles of explosion. There are some in Lisbon who say that the city is 'too full of blacks'. Along the waterfront stands an endless line of lorries. These carried the refugees out of Angola. Not all arrived and not many of their chattels. Almost empty of tourists, the best hotels, or whole floors of them, are given over to retornaclos living off the State, many of their children without schools or playgrounds.

Racism is more out of character, but the trauma of lost empire cuts deeper in Portugal than in England. The Portuguese were first into Africa--they were on the Guinea coast when the English were fighting the Wars of the Roses—and they were the last out. The Portuguese kept their sense of world mission when the allies who deserted them were making a virtue of the dubious necessity of scuttle. Nor was Portugal able to 'turn empire into commonwealth'. General Spinola's formulation proved not worth the paper on which his book Portugal and the Future was printed. Advantages such as Britain and the City of London retained in Commonwealth Africa were forfeit in the now Marxist U/trainar. The coffee, diamonds and iron ore are no longer Portugal's. She must turn from Africa to Europe for her main markets.

Yet the retornado aches for Africa even more distressingly than the Algerian piednoir who was more easily absorbed into Corsica or the Midi. Gilberto Freyre. the Brazilian exponent of the Luso-tropical ideal, described the restless Portuguese as almost a 'tropical expatriate who has wandered in Europe'. 0 Retornado is one of perhaps half a dozen successful weeklies of the Right. Those whose cause it champions will, if not enabled either to go back to Africa or to emigrate to Brazil or elsewhere, breed discontent and agitation in a precarious Portugal.

Dr Mario Soares himself would like Portugal to be the hyphen in 'Euro-Africa'. The two revolutions, that of April 1974 called by some the 'good' revolution in contrast to the tad' revolution of that autumn, moved the centre of politics so far Left that Dr Soares now appears a moderate, indeed an Iberian Callaghan. The Portuguese is more intellectual than his British counterpart and more middle-class. He is contemptuous of revolutionary romantics who idolise the proletariat. Like his authoritarian predecessors, Salazar and Caetano, he knows nothing of the military who sustain him. But they respect his courage and ability. Soares holds that the barracks is no place for revolutionary assemblies. He puts liberty before class struggle.

This, then, is a Portuguese unlike the hard Marxists who proscribed as 'fascist' Camoens, the national poet, and banned fatly and folksong. Dr Soares is a true Portuguese and a European. In Moscow he left Gromyko in no doubt of his fidelity to the Atlantic alliance.

Originally Marxist, the Socialist Party (PS), in a statement of principles analogous to the aims of the British Labour Party unchanged since 1918, prescribes the collectivisation of the means of production and distribution as a solution for national problems. But Dr Soares sees as clearly as Mr Callaghan that salvation lies in the capitalist ingredients of the mixed economy. Indeed he has been more outspoken than the British Prime .Minister in denouncing 'new forms of oppression' by trade unions. 'Only work can save us', he proclaims. Portugal must learn discipline again and outlaw strikes that wreck production. Already the Socialist government has begun to restore the illegally occupied land in Alentejo.

Dr Soares knows his enemy. A flirtation with the Young Communists inoculated him for life. The enemy is Soviet imperialism represented by the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP). Dr Soares told the French journalist D. Pouchin* that collaboration with the Right was as justifiable against Communism as was that of Communist, Action Francaise and Croix de Feu in the French Resistance to the Nazi invader. The alternative last November would have been a putsch by an external force such as the right-wing ELP (Portuguese Liberation Army). The Prime Minister also acknowledges the Church's decisive part in the revolt against Marxism and in particular the leadership of the Archbishop of Braga and the Bishop of Aveiro. He holds that anticlericalism destroyed the First Republic.

One man of the Right enjoying a good understanding with Mario Soares is General Carlos Galva() de Malo. This fearless. horsy and ambitious officer spoke out against Marxism when it was less safe than now to do so. Non-party, he sits in the National Assembly with the parliamentary group of the conservative CDS. He bitterly assails as unprincipled the decolonisation of Portuguese Africa. This was not accompanied by self-determination but, as in Guinea-Bissau, where the Cape Verdian 'colonists' of PA IGC supplanted the Portuguese, by massacres. Mozambique was handed to black minority rule under riuumo, which hold the cities but not the countryside (doubtless the incoming East German police will alter that !); Angola was abandoned to Cuban proxies of Russian imperialism.

Portugal was not defeated in Africa; she was subverted in Europe. The programme of the Armed Forces Movement ( M FA) never mentioned decolonisation, only a political and peaceful solution. Neither radical nor anti-colonialist opinions inspired the air force members of the Supreme Revolutionary Council who resented Lisbon's failure to replace dangerously antiquated military aircraft in Angola. The Estado Novo was not fascist—if fascism implies militarism. That thrifty genius, Salazar (who never saw the overseas provinces), and Dr Marcello Caetano after him, grudged the armed forces money and material.

Not being a military man, the Prime Minister is excluded from the Supreme Revolutionary Council. The chair belongs to the President of the Republic, General Eanes, with whom I talked for a full hour at the Palace of Belem. The President, speaking mostly off the record, expressed confidence in the ability of the British rapidly to overcome their present problems. He trusted in our institutions and 'the habits of democratic life'. Let there be an AngloPortuguese contribution to the building of Europe. A professional soldier, untainted by revolutionary or professional politics, solemn in appearance, he laughed but once during the interview—the General radiates an honest and serene determination.

He will need it. There is trouble ahead. The masses are weary of upheaval and elections. But Communists do not tire. Two revolutions and a counter-coup have turned Portugal from the prim, inefficient and relatively gentle regime of Dr Marcello Caetano—authoritarian not totalitarian— into a disorderly, permissive and fragile democracy.

The counter-coup of 25 November 1975 was directed against the red parachutists who occupied four air bases in an attempt to seize power and frustrate the secret ballot in which the Communists had failed miserably. The attempt failed. In a sense the paras fell victim to their own revolutionary indiscipline—orders must first be debated-

and their neglect of training, often rejected as 'fascist'. The restoration of military authority in most units, however, was most impressive and decisive.

November the 25th was perhaps a trap for the Marxists as was the abortive and unorganised march of the 'silent majority' for President Spinola in September 1974. En November the Armed Forces forestalled a Communist take-over which might have provoked a partition of Portugal at the Tagus between a Catholic and conservative north and the red belt in the middle. But the question is asked, and asked by democrats, whether the counter-coup went far enough. Inconclusive battles are commonly refought. I talked to Colonel Firmino Miguel at his skeleton Ministry of Defence. He held similar office in the first provisional government and in July 1974 General Spinola wanted him as Prime Minister. The revolutionary captains objected and the Marxist General Vasco Goncalves was appointed.

Colonel Miguel is a friendly and capable officer having the confidence of President Eanes. He is busy with the reduction and reorganisation of the armed forces for Nato and home defence and the rebuilding of a system of internal security which has hardly existed since the abolition of the DGS (Dr Caetano's less effective version of the Salazarist PI DE). A key figure was and is Colonel Renato Marques Pinto. He was fotunate to survive the revolutionary purge through being transferred from the London Embassy not to Lisbon but, as Chief of Staff, to Mozambique. Single-handed the Colonel ousted the Marxists controlling the co-ordinating body of military intelligence.

Portuguese staff officers are attracted by the British concept of highly trained, nonpolitical regular forces and, as bombs explode in Oporto and Lisbon, from left and right, are keen to learn from Ulster experience and our security forces' unrivalled skill in counter-insurgency and counterterrorism. The CDS leader, Dr Diogo Freitas do Amaral, sees a choice between 'the system of market economy' backed by the EEC and 'a communist system with the support of the Soviet Union'. As in Britain, the major threat to parliamentary demoncracy is from within the trade unions. In the white collar syndicates the PS have made gains; the Communists and far Left are entrenched among the metal workers, miners and railwaymen.

The Communists are armed. So are the devotees of General (now Major!) Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho. This populist demagogue was made by his genial personality, and by the media, into a potential Iberian Castro. I suspect, however, that he is pragmatic enough to be able to adapt his purposes to the doctrines of Bakunin or Proudhon who, more than Marx, inspired Portuguese socialism but also influenced the ideology of fascism. Otelo's appeal to the radical Left, particularly its youth, is demonstrated by the 16.2 per cent of votes cast for him in the Presidential election.

Nor does the revolutionary Left lack money, to judge, for example, by the excess of Marxist, Trotskyist and Maoist literature on sale alongside a mass of pornography.

The Communist chief, Dr Alvaro Cunhal, has stated that Portugal is only governable by dictatorship. Might he welcome a military coup and a new authoritarian regime which would be pilloried internationally as having made democratic Portugal the 'Chile of Europe,' unfit for the European community of nations?

The Communists have suffered humiliating defeat. Yet they are now able to condemn the austerity and pro-business programme of Dr Soares as a threat to the workers. Unlike Berlinguer and other EuroCommunists—the PCP opposes membership of the EEC—Dr Cunha] stands for one big trade union and a PCP-PS coalition foreshadowing a one-party system. On his side, Dr Soares would split the PS were he to enter into a coalition even with the social democrats of the PPD led by the small but courageous Oporto lawyer, Dr Francisco Sa Carneiro. So democracy is narrowly based at a time of national danger and insolvency.

So will the Socialist government endure beyond, say, the municipal elections in November ? Do the electoral successes of moderate parties and the Northern peasants' revolt against the Communists betoken a democratic maturity absent from the disastrous First Republic?

Or did Dr Cunhal speak truly?

Previous page

Previous page