The family way

Simon Hoggart

WE were in a pub garden in Berkshire. We'd brought beer from the tiny hatch in the bar itself out into the blazingly hot garden. There were battered trestletables, some with umbrellas over them, and plates full of delicious cold food. The view was of flower borders and an ancient church. With my family, including our children, then aged 13 and 10, were our friends Piers and Gerry, his mother and their baby daughter.

Someone remarked that several famous people lived in the neighbourhood, and at that moment in walked Lord Jenkins and his wife Jennifer. (`Walked' is, perhaps, not, as he would say, the mot juste; 'processed', perhaps.) Whereas the rest of us were in as few clothes as modesty permitted — shorts and T-shirts for the most part — the grandest of our political grandees was clad in the full figure, including a tweed jacket and a tie. He looked as unsuitably dressed as we would have done had we been preparing for a trip to the Antarctic, but there's no doubt that he made a majestic spectacle — the subject, perhaps. of a canvas to be unveiled with apt solemnity in the library of the Reform Club, or of at least three chapters in one of the A Dance to the Music of Time novels, with his lordship appearing as a more selfaware Widmerpool.

The Jenkins's host walked into the bar, and returned clanking with three bottles marked 'Good Ordinary Claret', which made me suspect that he did not know him all that well, for one does not associate the former leader of the Social Democrats with ordinary claret — good or otherwise. 'Good Ordinary Ch. Lafite 1964', perhaps.

But it did strike me as a quintessentially English scene, with the garden, the church, the ale cool but not chilled, and the unpretentious lunch enjoyed by one who was once a powerful statesman. And, of course, the children. The fact is that children are now as much a part of the pub scene as the beer, the food and the fruit-machines. It's the result of a change in habits as great as any since licensing hours were introduced during the first world war.

Ten years ago, about 90 per cent of all pubs were owned by the brewers, who saw them mainly in their traditional role as drinking dens — outlets for their product. Since then almost every large brewer, with the exception of Scottish & Newcastle, has got rid of its pubs, and now some 85 per cent are owned by companies that exist primarily to run the pubs, and which look on brewers as just another supplier. (Sometimes, as in the case of Bass Leisure, these are the result of the break-up of the giant breweries.) As a consequence, the new pubowners — who carry names such as Pubmaster, Punch, Wetherspoons — see the building as a unified leisure centre, usually tailored to a particular market, rather than as a bolt-hole for morose drinkers.

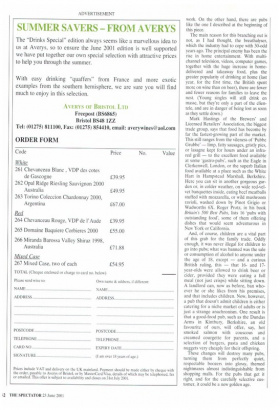

In some cases, the results have been horrible: we've all been into places with loud piped music, a vast selection of alcopops, a glossy generic menu that does not contain the name of the actual pub but brings the promise of microwaved food from some central depot in Swindon, banks of video games, and dirty tables with numbers on them so that you can do half the waitress's work. On the other hand, there are pubs like the one I described at the beginning of this piece.

The main reason for this branching out is not, as I had thought, the breathalyser, which the industry had to cope with 30-odd years ago. The principal enemy has been the rise in home entertainment. With multichannel television, videos, computer games, together with the huge increase in homedelivered and takeaway food, plus the greater popularity of drinking at home (last year, for the first time, the British spent more on wine than on beer), there are fewer and fewer reasons for families to leave the nest. (Young singles will still drink en masse, but they're only a part of the clientele, and are in danger of being lost as soon as they settle down.)

Mark Hastings of the Brewers' and Licensed Retailers' Association, the biggest trade group, says that food has become by far the fastest-growing part of the market. This still ranges from the vileness of Pubbe Grubb& — limp, fatty sausages, gristly pies, or lasagne kept for hours under an infrared grill — to the excellent food available at some `gastro-pubs', such as the Eagle in Clerkenwell, London, or the superb Italian food available at a place such as the White Hart in Hampstead Marshall, Berkshire. Here you can sit in another gorgeous garden or, in colder weather, on wide red-velvet banquettes inside, eating beef meatballs stuffed with mozzarella, or wild mushroom ravioli, washed down by Pinot Grigio or Wadworths 6X. Roger Protz, in his book Britain's 500 Best Pubs, lists 16 'pubs with outstanding food', some of them offering dishes that would seem adventurous in New York or California.

And, of course, children are a vital part of this grab for the family trade. Oddly enough, it was never illegal for children to go into pubs; what was banned was the sale or consumption of alcohol to anyone under the age of 18, except — and a curious British ruling, this — that 16and 17year-olds were allowed to drink beer or cider, provided they were eating a full meal (not just crisps) while sitting down. A landlord can, now as before, ban whoever he or she likes from his premises, and that includes children. Now, however, a pub that doesn't admit children is either catering for a niche market of adults or is just a strange anachronism. One result is that a good-food pub, such as the Dundas Arms in Kintbury, Berkshire, an old favourite of ours, will offer, say, hot smoked salmon with couscous and creamed courgette for parents, and a selection of burgers, pasta and chicken nuggets very cheaply for their offspring.

These changes will destroy many pubs, turning them from perfectly quiet, respectable boozers into glossy, themed nightmares almost indistinguishable from shopping malls. For the pubs that get it right, and for the carefully selective customer, it could be a new golden age.

Previous page

Previous page