ARTS

Ido not know whether Margaret Tarrant (of 'Jesus Among the Bluebells' fame) ever painted fairies, but if she had she would almost certainly have come up with some- thing like Nadine Baylis's set for the first act of the New D'Oyly Carte Opera Company's lolanthe. Words cannot de- scribe its hideousness or ineptitude. The old D'Oyly Carte Opera Company was proud of its chorus line of middle-aged and elderly fairies tripping hither, tripping thither; the new chorus would seem to be younger, but determined to act the part of middle-aged Savoyards having a good time. It is not an entirely convincing Performance. In their floppy diaphanous garments of drab, autumnal colours, gri- macing under repulsive headgear, they would have terrified any children in the audience, had there been any. The Arca- dian landscape is represented by three screens, looking like seed catalogues out of focus, behind an ugly and pointless rustic platform which reappears in Palace Yard, Westminster, in the dungeons of the Tower of London and on Tower Green by moon- light. The direction by Peter Walker is pretty feeble and the choreography by Petra Siniawski virtually non-existent.

All of which (except, perhaps, the per- functory choreography) might be described as being in the grand old D'Oyly Carte tradition, faithfully copied by amateur and school productions up and down the coun- try for as long as anybody alive can

Opera

Iolanthe (Cambridge Theatre)

Frightful fairies sing like angels

Auberon Waugh

remember. Where this production scores triumphantly is in the quality of the sing- ing. The chorus of fairies may look fright- ful — the peers are better on this point and they may spoil the lines by unintelli- gent over-acting (another grand old D'Oy- ly Carte tradition) but they sing like angels. The choral passages of 'When Britain really ruled the waves' had the effect of thrilling the audience into the sort of embarrassed emotion which one normally associates with 'Land of Hope and Glory' sung at a Conservative Party Conference. It is Gilbert and Sullivan's peculiar genius to be able to stir these emotions while simultaneously laughing at them. The acting may be poor (despite an agile and engaging Lord Chancellor in Richard Suart) but musically it is the most success- ful lolanthe I have ever heard. Perhaps the answer is to buy the records or tapes and avoid the performance.

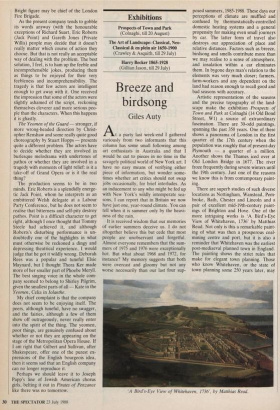

Having lavished such praise on the music, I must also say that I thought Bramwell Tovey took the overtures too reverently. I had forgotten what a poor score Sullivan wrote for the Yeomen over- ture, but the lolanthe one has some lovely passages which could have been taken with more verve. The great problem with Gil- bert and Sullivan operas is to decide whether we are dealing with a Victorian phenomenon, to be lovingly preserved in its own time capsule, or whether, as I maintain, they are timeless expressions of the English genius. Adoption of the first approach means that many of the jokes are dated and sometimes even incomprehensi- ble to all but devotees. The problem is particularly acute in lolanthe, with its references to current political anxieties like marriage with deceased wife's sister, and to contemporary personages like Captain Shaw of the London Fire Brigade. Adop- tion of the second approach can result in feeble and unfunny attempts to up-date the text and substitute whatever Sir Keith Eric Roberts (Jack Point) and Deborah Rees (Elsie Maynard) in The Yeomen of the Guard. Bright figure may be chief of the London Fire Brigade.

As the present company tends to gobble its words anyway (with the honourable exceptions of Richard Suart, Eric Roberts (Jack Point) and Gareth Jones (Private Willis) people may decide that it doesn't really matter which course of action they choose. But that is not really an acceptable way of dealing with the problem. The best solution, I feel, is to ham up the feeble and incomprehensible jokes, producing them as things to be enjoyed for their very feebleness and incomprehensibility. The tragedy is that few actors are intelligent enough to get away with it. One received the impression that some of the actors were slightly ashamed of the script, reckoning themselves cleverer and more serious peo- ple than the characters. When this happens it is ghastly.

The Yeomen of the Guard — stronger, if more wrong-headed direction by Christ- opher Renshaw and some really quite good choreography by Stuart Hopps — presents quite a different problem. The actors have to decide whether they are involved in burlesque melodrama with undertones of pathos or whether they are involved in a tragedy with moments of light relief: is it a take-off of Grand Opera or is it the real thing?

The production seems to be in two minds. Eric Roberts is a splendidly energe- tic Jack Point, whom he interprets as an embittered Welsh delegate at a Labour Party Conference, but he does not seem to realise that bitterness and self-pity destroy pathos. Point is a difficult character to get right, although I once thought that Tommy Steele had achieved it, and although Roberts's disturbing performance is un- doubtedly one of the highlights in what must otherwise be reckoned a dingy and depressing theatrical experience, I would judge that he got it wildly wrong. Deborah Rees was a popular and tuneful Elsie Maynard, but I thought Thora Ker made more of her smaller part of Phoebe Meryll. The best singing voice in the whole com- pany seemed to belong to Shirley Pilgrim, given the smallest parts of all — Kate in the Yeomen, Celia in lolanthe.

My chief complaint is that the company does not seem to be enjoying itself. The peers, although tuneful, have no swagger, and the fairies, although a few of them show off outrageously, never really enter into the spirit of the thing. The yeomen, poor things, are genuinely confused about whether or not they are appearing on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House. If I am right that Gilbert and Sullivan, after Shakespeare, offer one of the purest ex- pressions of the English bourgeois idea, then it seems sad that an English company can no longer reproduce it.

Perhaps we should leave it to Joseph Papp's line of Jewish American chorus girls, belting it out in Pirates of Penzance like there was no tomorrow.

Previous page

Previous page