Where Blair has gone wrong

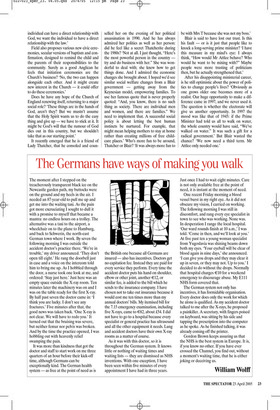

Frank Field tells Theo Hobson about Christianity, socialism — and the Prime Minister’s failure of leadership Iam expecting to meet Edmund Blackadder’s Puritan uncle, who frowns on suggestively shaped turnips, and worries that someone somewhere is having fun. But Frank Field does not fit the description. He’s smiley, forthcoming, chatty.

Field is more interesting than most exministers. He embodied New Labour’s early attempt at stern moral idealism and intellectual rigour — the Keith Joseph of the movement. He looks beyond party labels (he is a friend of Lady Thatcher); he writes books about the politics of behaviour and the Kingdom of God (he is a staunch Anglican). OK, so he wasn’t very effective as a minister, but what chance do you have when your agenda directly conflicts with Gordon Brown’s?

He was never really Old Labour, so what was he before Labour was made New? Christian socialist? ‘I steer clear of Christian socialism — I don’t like the term — it suggests an elite group that somehow understands truth better than other people. I’ve always felt that there are large numbers of Conservatives who are very decent people, who lead lives that are better than most of ours — it’s wrong to call them second-rate Christians because they’re not socialists. It’s offensive.’ But there was a ‘Christian socialist’ moment in the mid-1990s, wasn’t there? ‘When John Smith, who was very clearly a committed Christian, became leader, the party seemed full of Christians. One almost got knocked down in the crush to come forward and say, “Gosh, I’m a Christian too!” And dare one add, slightly cynically, certain people saw that might be a way to advance.’ Name some names? No? We move on.

Was the Christian socialist craze filling a void at a time when socialism began to seem a doomed ideology? ‘I don’t think the party ever had a strong ideological base. If you look at the formation of the Labour party, the socialists were the minority, they threw their lot in with the others. The socialists then took over its public ideology — but then what the hell do we mean by socialism? The best government we ever had was the Attlee government — not because it did socialist things, but because it actually carried through its programme of reform and also because of the quality of the people in it, the way they lived their lives — they never thought they were on the make.’ So the idea that Labour ought to be socialist is a sort of romantic illusion? ‘It’s a very useful crutch for some people to get through life with.’ A replacement religion? ‘Yes, and it becomes intolerable when such people present themselves as the only possessors of truth.’ Welfare reform was one of New Labour’s big ideas in 1997, and it was Field’s baby. But instead of putting him in charge, Blair made him Harriet Harman’s sidekick — they ended up sidekicking each other. The result is that welfare dependency has continued to grow under Labour. Why is this area so hard to reform? ‘Gladstone and Lloyd George got it right: any old fool can give people money; how do you give people money in a way that increases their freedom? This government has introduced complicated new rules surrounding welfare, but it has not tackled the question: what sort of character do you induce by that form of welfare?

‘And we now have a situation where it feeds itself. We now have the absurd situation of x millions of people on incapacity benefit, many of whom could work, and yet we have a huge issue about the number of foreign workers coming to this country to do jobs that they could do. And no one seems to make the connection between the two.’ So people should be encouraged to do jobs that they don’t want to do, rather than other people being invited into the country to do them instead? ‘Yes, absolutely. You can’t do that in one big blow, but the effort should be there. Instead the government increases incapacity benefit — it says that it will reform it in 2008!’ Does the case of welfare reform show that Blair is all talk, that he can’t see his radical plans through? ‘The crucial thing that distinguishes this government is the power struggle between No. 10 and No. 11, and that has not been resolved, even now.’ Which is surely a failure of leadership on Blair’s part? ‘Yes, of course. When John Smith died it was obvious in the PLP that Blair was going to become leader; he should have said, “Gordon, let’s fight it out” and there would have been no boil to lance later. And the power structure would have been clearly in place. Instead, you’ve got two people who want to do two lots of things.’ Field has suggested that the problem of yob culture can only be addressed if the police have far greater powers: they need to double up as surrogate parents for young tearaways, even if it means doubling up their funding. Does he mean it? ‘If you look at when we were a peaceable kingdom — if you go back 40 years — there was one police officer for every two crimes that were investigated. Now it’s one for every 44 crimes. Policing used to be about preventing crime; now it’s about managing it. Yes, I advocate more police powers but it’s also a long-term issue about how we raise children.’ How far can politicians tackle that issue? ‘Well, in the past it’s been the job of families and what’s called civil society: workplaces, trade unions, churches, all of them imposing agreed rules of conduct. That’s largely been stripped away. So we’re back to where the Greeks were. Greek politics was essentially about asking: what sort of individuals, characters should we and our fellow citizens be?’ That means politics has to take on the role of religion? ‘It has to go back to first principles again, given that civil society has weakened — not just churches: trade unions were very tough at enforcing proper behaviour. The welfare state came through mutual aid and friendly societies, which had very clear rules about how to behave. You had local hierarchies — for example, we had a shipyard and a steelworks in Birkenhead — if you didn’t behave at the works you were taken behind the shed and dealt with, because you couldn’t have people risking other people’s limbs and lives. Those sort of communities, in a very short space of time, have collapsed.’ So that means the state must be stronger, to fill the void? ‘The problem is, to tackle antisocial behaviour at present you have to mediate through professionals — social workers, youth officers, drug teams — and they always have a reason for not doing anything. So the challenge is to empower communities to get swift action — the criminal justice route is too slow; there has to be a quick way of using the authority of the courts to enforce order locally. That’s the way back to self-governing communities — to get away from all these professionals. We need a reformation — just as Luther said that the individual can have a direct relationship with God, we want the individual to have a direct relationship with the law.’ Field also proposes various new civic ceremonies, secular versions of baptism and confirmation, designed to remind the child and the parents of their responsibilities to the community. Surely as a good Anglican he feels that initiation ceremonies are the Church’s business? ‘No, the two can happen alongside each other. And it might create new interest in the Church — it could offer to do these ceremonies.’ Does he have any hope of the Church of England renewing itself, returning to a major social role? ‘These things are in the hands of God, aren’t they? But we mustn’t assume that the Holy Spirit wants us to do the easy thing and give up — we have to stick at it. It might be God’s will that the rumour of God dies out in this country, but we shouldn’t take that as our starting point.’ It recently emerged that he is a friend of Lady Thatcher, that he consoled and coun selled her on the evening of her political assassination in 1990. And he has always admired her politics as well as her person: did he feel like a secret Thatcherite during the 1980s? ‘Not at all. I just thought, “Here’s the most powerful person in the country try and do business with her.” She was wonderful to deal with; she knew how to get things done. And I admired the economic changes she brought about. I hoped we’d see similar social welfare changes from a Blair government — getting away from the Keynesian model, empowering families. To use her famous quote that is never properly quoted: “And, you know, there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families.” We need to implement that. A successful social policy is about letting the best human instincts be nurtured. For example, that might mean helping mothers to stay at home rather than creating millions of free childcare places.’ Who’s more fun to be around, Thatcher or Blair? ‘It was always more fun to be with Mrs T because she was not my boss.’ Blair is said to have lost our trust. Is this his fault — or is it just that people like to knock a long-serving prime minister? ‘I have this measure in my mind’s eye: I always think, “How would Mr Attlee behave? Who would he want to be mixing with?” Maybe people were more trusting of politicians then, but he actually strengthened that.’ After his disappointing ministerial career, is he still optimistic about the power of politics to change people’s lives? ‘Obviously as one grows older one becomes more of a realist. Our huge opportunity to make a difference came in 1997, and we never used it. The question is whether the electorate will give us another opportunity. In 1997 the mood was like that of 1945: if the Prime Minister had told us all to walk on water, the whole country would have said, “We’ve walked on water.” It was such a gift for a radical government.’ But Blair wasted the chance? ‘We now need a third term. Mr Attlee only needed one.’

Previous page

Previous page