THE WAY WE WERE

Sir Edward Ford, who was assistant private secretary to both the Queen and her father,

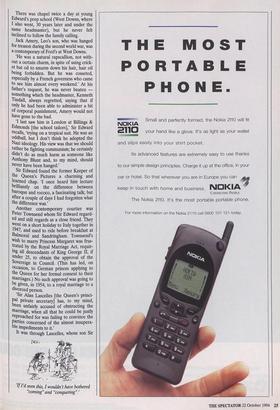

gives an audience to Simon Courtauld `HYDE PARK CORNER,' said Sir Edward Ford. `That was the message I received by telephone from Sandringham on the morning of 6 February 1952. It meant that the King was dead.

`It was a bad code. The decision was taken to send the same three words by telegram to Kenya [where the new Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh were staying, on the first leg of a tour that would have taken them to Australia and New Zealand]. But the telegram never arrived. I don't know why, but my own view is that the telegraphist thought that Hyde Park Corner was just the place of origin, and, since there was no message, there wasn't any point in sending it.'

Sir Edward has a vivid memory of that morning. He had been assistant private secretary to George VI since 1946 and was to continue doing the same job for the Queen until 1967. On that day his first duty was to take the news to the Prime Minister and Queen Mary. He went first to Downing Street. `I parked my car outside Number 10 and was taken to see Churchill in bed. I remem- ber there were papers all round him and a green candle on the bedside table to relight the cigar which he had in his mouth.'

When Sir Edward got to Marlborough House, Queen Mary's lady-in-waiting, Lady Cynthia Colville, tried to dissuade him from blurting out the news because, she said, Her Majesty had been so upset by the abrupt way in which she had been given the news of the Duke of Kent's death in the war. But Sir Edward prevailed, saying that the King's death would be announced by the BBC within the hour. The BBC, how- ever, was unprepared.

`We told the BBC as well as the Press Association and Reuters that the news could be released at ten forty-five, and whenithe time came we switched on the radio to hear it. Nothing happened. We waited until the eleven o'clock news, and still there was nothing. The BBC's morning physical train- ing programme continued relentlessly.

`Apparently the people at the BBC were deep in conference, deciding how best to make the announcement. It was thought that the only person who could be trusted to do the job with proper dignity was John Snagge, and he couldn't be found.'

The Duke of Norfolk arrived at the Palace not long afterwards, having seen a newspaper headline at Victoria station. The evening papers had got the news on to the streets in the time it took Auntie Beeb to work out what to do. Mention of the Duke of Norfolk prompts Sir Edward into another anecdote.

`A few months before the coronation, a peer came to see the Duke, saying how much he wanted to attend the service, but that he was afraid that he might not receive an invitation because he had been divorced. To which the Duke replied, "Good God, man, this is a coronation, not Royal Ascot."

Sir Edward had the benefit of an ecclesi- astical background — brought up, as he puts it, `encircled by dog collars'. His father was Dean of York, his maternal grandfa- ther Bishop of Winchester, one of his uncles was Bishop of Pretoria, another was a monk, and his eldest brother also took holy orders. There was chapel twice a day at young Edward's prep school (West Downs, where I also went, 30 years later and under the same headmaster), but he never felt inclined to follow the family calling.

Jack Amery, Leo's son, who was hanged for treason during the second world war, was a contemporary of Ford's at West Downs.

`He was a natural rapscallion, not with- out a certain charm, in spite of using crick- et bat oil to smarm down his hair, hair oil being forbidden. But he was cosseted, especially by a French governess who came to see him almost every weekend.' At his father's request, he was never beaten - something which the headmaster, Kenneth Tindall, always regretted, saying that if Only he had been able to administer a bit of corporal punishment, Amery would not have gone to the bad.

`I last saw him in London at Billings & Edmonds [the school tailors],' Sir Edward recalls, 'trying on a tropical suit. He was an oddball, but I don't think he adopted the Nazi ideology. His view was that we should rather be fighting communism; he certainly didn't do as much harm as someone like Anthony Blunt and, to my mind, should never have been hanged.' Sir Edward found the former Keeper of the Queen's Pictures a charming and learned chap. 'I once heard him lecture brilliantly on the difference between baroque and rococo, a fascinating talk; but after a couple of days I had forgotten what the difference was.'

Another contemporary courtier was Peter Townsend whom Sir Edward regard- ed and still regards as a close friend. They went on a short holiday to Italy together in 1947, and used to ride before breakfast at Balmoral and Sandringham. Townsend's wish to marry Princess Margaret was frus- trated by the Royal Marriage Act, requir- ing all descendants of King George II, if under 25, to obtain the approval of the Sovereign in Council. (This has led, on occasion, to German princes applying to the Queen for her formal consent to their marriages.) No such approval was going to be given, in 1954, to a royal marriage to a divorced person. `Sir Alan Lascelles [the Queen's princi- pal private secretary] has, to my mind, been unfairly accused of obstructing the marriage, when all that he could be justly reproached for was failing to convince the parties concerned of the almost insupera- ble impediments to it.'

It was through Lascelles, whose son Sir If I'd seen this, I wouldn't have bothered "coming" and "conquering".' Edward had tutored in Canada in 1934, that he got the Palace job after the war. In 1936/37 he had spent another year as English tutor to the young King Farouk of Egypt. But he saw little of his charge, and the teaching was minimal. As a classical scholar (Eton and New College, Oxford), Sir Edward did not know in which subjects he should try to instruct the 16-year-old monarch of a country just declared inde- pendent from Britain. 'Teach him not to lose his temper when you beat him at ten- nis,' was the advice of the British Ambas- sador, Sir Miles Lampson, later Lord Killearn. Twenty-five years later, when Sir Edward saw Farouk in St Moritz, Farouk kept asking him about Lord Halifax. 'I couldn't think why, unless he imagined that I had been a Foreign Office spy.'

Sir Edward enjoys recalling the various foreign trips he made in the first 15 years of the Queen's reign — to Norway, Hol- land, Nigeria, France, India, Iran, Ethiopia and the Caribbean. As assistant private secretary, he went out ahead to make the arrangements, and was royally treated in each country.

`It is remarkable to compare the extent of her travels with those of her father and grandfather,' Sir Edward said. 'George VI was prevented, by the war and later by ill health, from going to many countries; and George V hardly went anywhere, apart from a durbar in India in the first year of his reign. The Queen has visited all the countries of the Commonwealth, some of them, like Australia, Canada and New Zealand several times — in spite of her domestic duties and the necessity for her to fulfil her constitutional role as head of state of the United Kingdom. And yet John Grigg thinks that the Queen should spend more time visiting the Common- wealth and should have houses in several of its countries!'

Sir Edward hastens to add that Grigg and he get on well together, and it occurs to me that it would be very difficult not to get on with this bonhomous 84-year-old ex-courtier, who is wearing a pepper-and- salt jacket and waistcoat not dissimilar in colour to his hair. Although he was cocooned in the Palace for most of his 21 years as a member of the royal household, journalists are not unknown to him. Indeed, one of his sons is business manag- er of the Oldie magazine and married to the daughter of the editor, Richard Ingrams; and James Fox, author of White Mischief, is his wife's nephew.

Whether or not such connections have inured him to press criticism of the royal circle, Sir Edward is able to laugh — he does a lot of laughing — at much of the recent adverse media comment.

`Having listened to a lot of talk about cost-cutting by the monarchy, the public is now fed the idea of a large number of sycophantic, fainéant courtiers getting paid too much and living lives of luxury in grace-and-favour apartments. The truth is that until recently courtiers have been notoriously poorly paid. I and several of my colleagues in the royal household could not have stayed in the job had we not had rich wives or private means. We used to jest that our decorations in the Victorian Order should more aptly have been conferred on our wives!' (Since 1975 Sir Edward has been Secretary of the Order of Merit, at the same remuneration as the first Secre- tary received 92 years ago.) To those critics who would like to abolish the monarchy and replace it with an elected presidency, Sir Edward responds, 'Would they really have the same respect for Roy Hattersley or David Owen residing in Buck- ingham Palace as President of the British Republic? One of the great advantages of having a monarch is that we don't have to argue about who should be head of state.'

But there is a lot of argument about the `perks' of the head of state. Sir Edward is not in favour of scrapping the royal yacht Britannia — 'though it should perhaps have been used more. Britannia has enabled the Queen not only to visit places that would have been inaccessible by other means but also to act as hostess to heads of state in an equally glamorous but less formal and less expensive way than by a state visit to Buck- ingham Palace.

`I think the state visits are rather over- done; the foreign heads of state are not always friendly, and the visits often have virtually nil result — except, of course, to dislocate the traffic.'

It was Sir Edward who, two years ago, coined the term annus honibilis, in a letter to the Queen's private secretary. It has been perhaps the most famous soundbite of the decade — with no less relevance to this year, in particular to this mensis horn- bilis for the royal family.

`I think she is the best monarch we have had for 400 years, admired throughout the world and deeply respected for her judg- ment. She shouldn't be tarred with the flaws of other members of the family many of whom, however, work extremely hard in the public interest.'

As I left Sir Edward's house off the Edg- ware Road in Little Venice — Lord Hare- wood used to live on one side and Lady Diana Cooper's son, Lord Norwich, lives on the other — I had the feeling that he is quite relieved not to be at the Palace these days.

Previous page

Previous page