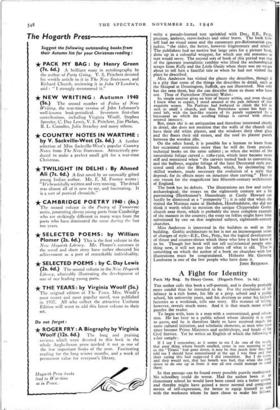

A Good Antiquarian

Tins is a chatty book about old churches. Unlike many chatty writers, Miss Anderson is accurate and, unlike many accurate writers, she is readable. She is at heart an antiquarian, inter- ested in mediaeval carving; in recesses, recumbent effigies and other stone relics which peep about among the hot-water pipes, brooms, powder-blue hangings and modern unstained oak of our old churches. But her antiquarianism is neither prejudiced nor date-ridden, and though the arrangement of the book is hap- hazard—for it is a series of little essays on various church sub- jects such as Easter Sepulchres, The Tree of Jesse, Carved Ele- phants in Devon, Wool churches, in various parts of England and Wales—the approach to the subject is refreshing. The book is written to interest the uninitiated in old churches and to keep a picture in the author's mind, and that of her readers, of English landscape. "One day, for some of us, the common day- light will return, but while we are still in the fog we must keep some mental image of normal things to be the haven of our imaginations." This refers to the war, and not to winter. She clearly wrote the book out of delight in her subject, and not for money. That is one reason for the book having the right approach. We have so long been used to the wrong approach to church architecture that we are inclined to forget how useful even a slight book like this can be. In Edward VII's reign, and during the first few years of that of George V, many sumptuous and fully-illustrated volumes on

English churches appeared. Their text was nearly always un- readable, for those scholarly volumes were primarily reference books for the use of antiquarians, with the strong and still pre- vailing prejudice for pre-Reformation work. When motor trans- port after the last war brought the country to townspeople, two vilely harmful sorts of books appeared and sold in thousands. The first was an indiscriminate rehash of the old, scholarly books— the photographs were reprinted, and a hack was employed to

write a pseudo-learned text sprinlded with Dec., E.E., Perp., piscinae, ambries, stave-lockers and other bores. The hack him- self had no visual sense and the customary pre-Reformation pre- judice, "the older, the better, however fragmentary and crude." The publishers had no motive but large sales for a picture book, done up in a colourful wrapper, for which any old nonsense as text would serve. The second sort of book of this period was that of the ignorant journalistic rambler who lifted the archaeological scraps from Kelly and the Little Guide when there was no verger about to tell him a fanciful tale or when he had not visited the place he described.

Miss Anderson has visited the places she describes, though it is a pity that some of the things she describes in detail, such as the Skiapod at Dennington, Suffolk, are not illustrated. Not only has she seen them, but she can describe them to those who have not. Thus of Partrishow (Patricio) Wales:

Its simple exterior gives no hint of beauty within, and even though I knew what to expect, I stood amazed at the pale delicacy of that exquisite screen. No Puritans had bothered to climb the hill to sack so small a church, and thus Partrishow screen has kept its rood loft, with the lace-like tracery of its panels supported by a bressumer on which the scrolling foliage is carved with almost oriental intricacy.

But, since she is an antiquarian and therefore interested chiefly

in detail, she does not mention that the walls of the church still have their old white plaster, and the windows their clear glass and thz. floors their old stones, and the roof its plaster panels between the wooden ribs.

On the other hand, it is possible for a layman to learn from

her occasional sentences more than he will do from pseudo- technical books on the same subject ; as when she writes of the naturalistic foliage carved c. 1280-1310, which later became more stiff and restrained when "the carvers turned back to convention, and the bulbous, angular foliage of the later Decorated style per- sisted until after the Black Death, which, by decimating the skilled workers, made necessary the evolution of a style that depend, for its effects more on structure than carving." Here is one reason for the magnificent late fifteenth-century architecture of England.

The book has its defects. The illustrations are few and rather

archaeological; the essays on the eighteenth century are a bit patronising (Hawksmoor's Mausoleum at Castle Howard can hardly be dismissed as a " pomposity ") ; it is odd that when she visited the Norman ruins at Shobdon, Herefordshire, she did not think it worth while to mention the unique Chippendale Gothic church near them, which is probably the most complete example of the manner in the country; the essay on follies might have been substituted by one on that neglected subject, eighteenth-century churches.

Miss Anderson is interested in the builders as well as the

building. Gothic architecture to her is not an inconsequent series of changes of style—E.E., Dec., Perp., but the logical development of thrust and counter-thrust which those who love it best know it to be. Though her book will not tell ecc:esiastical people any- thing new, it will not put the others off what is old. That is something on which the author of a book on churches with few illustrations must be congratulated. Hitherto Mr. Greming Lamborne is one of the few people who have done it.

JOHN BETJEMAN.

Previous page

Previous page