The patron saint of historians

Eric Christiansen

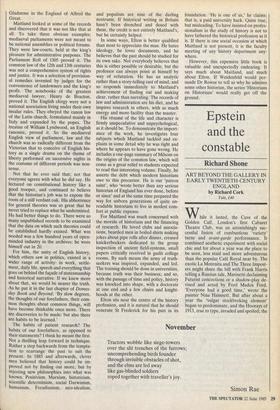

F. W. MAITLAND by G. R. Elton

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £12.95

It is strange that two of the most arro- gant men in England are Tudor historians. You would suppose that men lucky enough to be paid for investigating that remote but colourful period would congratulate them- selves on their good fortune as more than they deserve. Their opportunities for pri- vate amusement and inoffensive industry must be endless. The approbation of their families and friends might afford them more pleasure than the hollow victories of paper warfare. But that is not how they see it.

They play to win. They brook no contra- diction. They bang and bawl. For many years, they have been putting the public right from postures of authority. We are all the wiser for their words, and the force behind them. It is difficult to decide whether England owes more to the arro- gance of Dr Rowse, or to the arrogance of Professor Elton; but the question is keenly debated at meetings of the British Academy and other responsible public bodies which well those passions know. Not all historians are like that. The most unlike was Frederick William Maitland.

He was a modest man, with little to be modest about: charming, unobtrusive and inoffensively honourable. It is difficult for even a modern biographer to crab at anything he ever did, apart from the naming of his daughters: Fredigond and Ermengard. As for his writings, I dare say that if the work of all the men and women who have attempted to write history in English over the last hundred years were suddenly to disappear, and the works of Maitland were to survive, history would be much better taught within our universities and much better understood in general.

That may look like an odd claim. What is odder is that a great many historians would agree with me. Oddest of all, Professor Elton has given his assent to the spirit of the claim, if not to the letter. And now he has taken his admiration to the extent of undertaking that most difficult task, of explaining why Maitland was so good.

There are three big difficulties. Firstly, he wrote much about things which repel readers by their technicality and apparent remoteness: mediaeval law and mediaeval records. A piece entitled The early history of Malice Aforethought' is never likely to attract a mass audience. He had the gift of making this stuff intelligible and immedi- ate. No one can rival him there, but the materials have to be described to appreci- ate the achievement of the artist. Such description is apt to be dull.

Secondly, there is the attractiveness of his style, which speaks for itself, and which some consider his forte. What can a biog- rapher do about it? Elton takes the Spartan line, and refuses to quote at length. This is admirable, but disappointing. Reading ab- out caviare is a poor substitute for eating it. And thirdly, the recbrd of what Maitland explored and suggested is largely a list of things which we now take for granted. Analysing his originality can seem like stating the obvious. The instinct of a modern historian is to show where he went wrong; but to do that is to sound governes- sy. It is a risk that Elton is prepared to run. Maitland was an unfee'd barrister with a good Cambridge education who started writing history in his mid-thirties, exactly a 100 years ago. He worked very hard for 20 years, and died of double pneumonia in the Canaries, where he used to bicycle for his health. He came to his task with no preconceptions about the purpose and nature of history other than the conven- tional ones of his day: that English history was essentially the study of the English constitution as it had progressed from Anglo-Saxon times to Queen Victoria's through a series of conflicts and comprom- ises between the people and their rulers.

The great national institutions of parlia- ment, the common law, and the church of England were the result, but they had always been there in embryo. The discern- ing eye could detect the England of Mr

Gladstone in the England of Alfred the Great.

Maitland looked at some of the records and discovered that it was not like that at all. To take three obvious examples: mediaeval parliaments were not meant to be national assemblies or political forums. They were law-courts, held at the king's pleasure for administrative purposes. The Parliament Roll of 1305 proved it. The common law of the 12th and 13th centuries was not a comprehensive system of rights and justice. It was a selection of provision- al remedies invented by judges for the convenience of landowners and the king's profit. The notebooks of the greatest mediaeval lawyer, Henry de Bracton, proved it. The English clergy were not a national association living under their own insular rules. They obeyed the 'canon law of the Latin church, formulated mainly in Italy and expanded by the popes. The treatise of William Lyndwood, an English canonist, proved it. So the mediaeval English view of parliament, law and the church was so radically different from the Victorian that to conceive of English his- tory as a single drama on the theme of liberty performed on successive nights in the costume of different periods was non- sense.

Not that he ever said that; not that everyone agrees with what he did say. He lectured on constitutional history like a good trooper, and continued to believe that the historian's job was to expose the roots of a still verdant oak. His abhorrence for general theories was so great that he never tried to replace what he undermined. He had better things to do. There were so many unpublished records to be examined that the data on which such theories could be established hardly existed. What was needed was a few hundred years of open- minded industry in the archives: he wore himself out in 20.

For him, the unity of English history, which others saw in politics, existed in a wider range of activity: in work, settle- ment, daily life, speech and everything that goes on behind the façade of statesmanship and historical narrative. If we knew more about that, we would be nearer the truth. As he put it in the last chapter of Domes- day Book and Beyond: 'By slow degrees,

the thoughts of our forefathers, their com- mon thoughts about common things, will have become thinkable once more. There are discoveries to be made: but also there are habits to be learned.'

The habits of patient research? The habits of our forefathers, as opposed to their statements? I think he meant the first.

Not a thrilling leap forward in technique. Rather a step backwards from the tempta- tion to rearrange the past to suit the present. In 1885 and afterwards, clever men believed that history could be im- proved not by finding out more, but by injecting new philosophies into what was known. Positivism, Marxism, historicism, scientific determinism, social Darwinism, humanism, Freudianism, neo-idealism, and populism are nine of the darling nostrums. If historical writing in Britain hasn't been drenched and dosed with them, the credit is not entirely Maitland's, but he certainly helped.

In some ways, Elton is better qualified than most to appreciate the man. He hates ideology, he loves documents, and he believes that the past should be studied for its own sake. Not everybody believes that this is either possible or desirable, but the professor can always point at himself by way of refutation. He has an analytic rather than a story-telling cast of mind, and so responds immediately to Maitland's achievement of finding out and making clear, rather than narrating. The records of law and administration are his diet, and he inspires research in others, with as much energy and more facility than the master.

His résumé of the life and character is firmly unspeculative and unpsychological, as it should be. To demonstrate the import- ance of the work, he investigates four subjects which Maitland tackled and ex- plains in some detail why he was right and where he appears to have gone wrong. He includes a one-page summary of Milsom on the origins of the common law, which will come as a great relief to students expected to read that interesting volume. Finally, he asserts the debt which modern historians owe to this precursor. He is our 'patron saint', who 'wrote better than any serious historian of England has ever done, before or since' and at the same time prepared the way for unborn generations of quite un- readable historians to live in modest com- fort at public expense.

For Maitland was much concerned with the morale of historians and the financing of research. He loved clubs and associa- tions, bearded men in boiled shirts making jokes about pipe rolls after dinner, creased knickerbockers dedicated to the group inspection of ancient field-systems, small papers critically received in gaslit college rooms. By such means the army of truth- seekers was inspired, expanded, and led.

The training should be done in universities, because truth was their business; and so, with the passage of time and policy, history was knocked into shape, with a doctorate at one end and a few chairs and knight- hoods at the other.

Elton sits near the centre of the history profession, and it is natural that he should venerate St Frederick for his part in its foundation. 'He is one of us,' he claims: that is, a paid university hack. Quite true, but misleading. To have insisted on profes- sionalism in the study of history is not to have fathered the historical profession as it is. If there is one social occasion at which Maitland is not present, it is the faculty meeting of any history department any- where.

However, this expensive little book is valuable and unexpectedly endearing. It says much about Maitland, and much about Elton. If Weidenfeld would per- suade Dr RoWse to tell us why he admires some other historian, the series 'Historians on Historians' would really get off the ground.

Previous page

Previous page