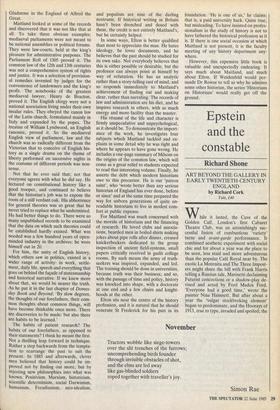

Epstein and the constable

Richard Shone

ART BEYOND THE GALLERY IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND by Richard Cork Yale, £40 While it lasted, the Cave of the Golden Calf, London's first Cabaret Theatre Club, was an astonishingly suc- cessful fusion of rumbustious 'variety' turns and avant-garde performance. It combined aesthetic experiment with social chic and for about a year was the place to be seen, less staid and more adventurous than the popular Café Royal near by. The exotic La Morenita and The Three Impost- ers might share the bill with Frank Harris telling a Russian tale, Marinetti declaiming Futurist concoctions or a shadow-play de- vised and acted by Ford Madox Ford. 'Everyone had a good time,' wrote the painter Nina Hamnett. But after about a year the 'vulgar stockbroking element' began to predominate, and the Hoorays of 1913, true to type, invaded and spoiled; the

artists and writers for whom Mme Strind- berg had started the venture were less inclined to attend and could no longer afford it; in early 1914, after 18 months existence, the Club closed down with a sale of liquidation. The frustrating thing is that no one since has traced any of the murals and sculpture by Wyndham Lewis, Ginner, Gore, Epstein and Eric Gill — which decorated the premises and made it the most remarkable interior described in this book.

When researching and writing his monumental study of Vorticism (published ten years ago), Richard Cork was capti- vated by the attempts artists had made to contact a public beyond the confining walls of the gallery. Many of the Vorticist, Camden Town and Omega Workshops artists in the years 1910 to 1920 turned their hands to an astonishing variety of projects, public and private. The decora- tive possibilities of the new European movements in painting inspired a ferment of activity in the avant-garde. And what was often thought reprehensible, even shocking, in a frame on a wall was more acceptable when viewed as a decorative object or part of a designed interior. And so a mass of schemes was undertaken; by 1914, for example, there was a club, a café, a restaurant, a students' dining-room and several much-visited private houses all sporting the last word in up-to-date decora- tion carried out by some of the most notable names in British art of the period. Some of it, admittedly, was rather trying in its explosive scale and brittle colour, guyed by Arnold Bennett in his novel The Pretty Lady. But Richard Cork has chosen to describe several projects which were not- ably careful and thought through, in which the artists sensitively adapted new imagery and colour to older interiors (as often was the case of the Omega artists) or, as with Epstein for the British Medical Association building in the Strand, were careful to integrate their work with a new building. All this sounds fine, and, if things had gone to plan, we should have a rich visual legacy from an exciting moment. Instead, Cork unfolds a lamentable story of public outcry and censorship, of neglect and destruction and official indifference. And he does this with a superbly reconstructive eye and a controlled indignation. It is thus a pleasure to read but depressing to think about as the catalogue mounts of works destroyed, lost or obscured. And the first chapter on Epstein in the Strand sets the tone for the rest of the book.

Have you ever looked up at Zimbabwe House on the corner of Agar Street and the Strand? If you did, you would see a pathetic frieze of mutilated figures, 18 in all, more reminiscent of Dachau than the dignified embodiments of the ages of man. A combination of neglect, change of own- ership and official disapproval brought about the terrible fate of one of the best collaborations in London between architect (Charles Holden) and sculptor.

At the time Epstein was carving his figures (1908), most new structures in London were adorned with contemptible, off-the- peg symbolic figures and degraded plaster decorations sold at so much a yard. Epstein set an example which was alas rarely followed and he himself was not asked to

collaborate on a new building again for 20 years. When he did — making Night and Day for the Underground Head Offices, St James's Park station — the outcry was even greater, Day being tarred and feath-

ered and then nearly removed; Epstein had the humiliating task of cutting off about an inch and a half from the penis of the small

boy represented in the work to appease the outraged British public and incensed share- holders of the Underground Railway Com- pany. On another part of the building is one of Henry Moore's most satisfying and colossal conceptions, the portland stone relief West Wind, and two panels by Eric Gill. They received further commissions, but Epstein was once more left out in the cold, and when Holden was appointed as architect for the new Senate House, it was on the understanding that Epstein was excluded from any sculptural decoration there might be.

The other projects lovingly revived by Cork include a Wilton Crescent dining- room by Wyndham Lewis which reflected the occult interests of its owner Lady Drogheda, and Lewis's decorations for Madox Ford and Violet Hunt at South Lodge; several schemes by the Omega artists including a Cadena Café in West- bourne Grove where Roger Fry even chose the waitresses' uniforms, murals in Ber- keley Street and in Chelsea; only a mosaic pavement survives in situ, at 1 Hyde Park Gardens. And lastly there is an account of the Eiffel Tower restaurant, Percy Street (now the White Tower); alas, of the surprising canvases there by Lewis and William Roberts only two have emerged since the public sale of the contents in 1938. Not even a photograph of the cele- brated Vorticist room has emerged, and, if Richard Cork has not found one, then I doubt if one exists.

Cork's research seems faultless, and his text is abundantly illustrated with draw- ings, studies and newspaper photographs which miraculously convey some of the impact of these clamorous interiors. It is nice, rare even, to detect in an art histo- rian's prose both enthusiasm and humour hand in hand with rigorous iconographic explorations. He shows a greater grasp of

the social complexion of the period than he did in his Vorticism. And a natural fair-

mindedness prevents any intemperate out- bursts at the philistine and hypocritical sneers of Fleet Street and officialdom; he can see the joke of Epstein's stone tits and cocks positioned bang opposite the inquisi- tive windows of a Whitehousian organ, the National Vigilance Association, who sent a constable up the scaffolding and began the whole sorry business.

Previous page

Previous page