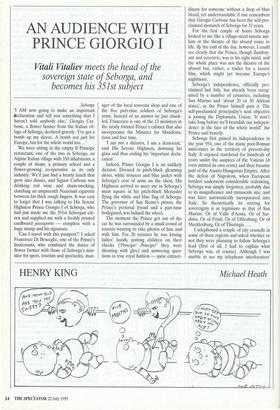

AN AUDIENCE WITH PRINCE GIORGIO I

Vitali Vitaliev meets the head of the

sovereign state of Seborga, and • becomes his 351st subject

Seborga 'I AM now going to make an important declaration and tell you something that I haven't told anybody else,' Giorgio Car- bone, a flower farmer from the Italian vil- lage of Seborga, declared gravely. 'I've got a bomb up my sleeve. A bomb not just for Europe, but for the whole world too. ..'

We were sitting in the empty II Principe restaurant, one of the two in Seborga, an Alpine Italian village with 350 inhabitants, a couple of shops, a primary school and a flower-growing co-operative as its only industry. We'd just had a hearty lunch that grew into dinner, and Signor Carbone was drinking red wine and chain-smoking, clutching an umpteenth Nazionali cigarette between his thick rough fingers. It was easy to forget that I was talking to His Serene Highness Prince Giorgio I of Seborga, who had just made me the 351st Seborgan citi- zen and supplied me with a freshly printed cardboard passaporto — complete with a huge stamp and his signature.

'Can I travel with this passport?' I asked Francesco Di Besceglie, one of the Prince's lieutenants, who combined the duties of flower fanner with those of Seborga's min- ister for sport, tourism and spectacles, man- ager of the local souvenir shop and one of the five part-time soldiers of Seborga's army. Instead of an answer he just chuck- led. Francesco is one of the 13 ministers in the newly formed Prince's cabinet that also incorporates the Minister for Manifesta- tions and free time.

'I am not a dictator, I am a democrat,' said His Serene Highness, downing his glass and thus ending his 'important decla- ration'.

Indeed, Prince Giorgio I is an unlikely dictator. Dressed in pitch-black gleaming shoes, white trousers and blue jacket with Seborga's coat of arms on the chest, His Highness arrived to meet me in Seborga's main square in his pitch-black Mercedes flying the white and blue flag of Seborga. The governor of San Remo's prison, the Prince's personal friend and a part-time bodyguard, was behind the wheel.

The moment the Prince got out of the car he was surrounded by a small crowd of tourists wanting to take photos of him and with him. For 20 minutes he was kissing ladies' hands, patting children on their cheeks (Principe! Principe!' they were shouting with glee) and answering ques- tions in true royal fashion — quite extraor- dinary for someone without a drop of blue blood, yet understandable if one remembers that Giorgio Carbone has been the self-pro- claimed monarch of Seborga for 32 years.

For the first couple of hours Seborga looked to me like a village-sized lunatic asy- lum or the theatre of the absurd come to life. By the end of the day, however, I could see clearly that the Prince, though flamboy- ant and eccentric, was in his right mind, and the whole place was not the theatre of the absurd but, rather, a trailer for a horror film, which might yet become Europe's nightmare.

Seborga's independence, officially pro- claimed last July, has already been recog- nised by a number of countries, including San Marino and 'about 20 or 30 African states', as the Prince himself puts it. The self-proclaimed principality's next objective is joining the Diplomatic Union. 'It won't take long before we'll brandish our indepen- dence in the face of the whole world!' the Prince said bravely.

Seborga first gained its independence in the year 954, one of the many post-Roman mini-states in the territory of present-day Italy. It enjoyed statehood for hundreds of years under the auspices of the Vatican (it even minted its own coins) and then became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After the defeat of Napoleon, when European borders underwent considerable redrawing, Seborga was simply forgotten, probably due to its insignificance and minuscule size, and was later automatically incorporated into Italy. So theoretically its striving for sovereignty is as legitimate as that of San Marino. Or of Valle d'Aosta. Or of Sar- dinia. Or of Friuli. Or of Oldenburg. Or of Mecklenburg. Or of Thuringia . . .

I telephoned a couple of city councils in some of these regions and asked whether or not they were planning to follow Seborga's lead (first of all, I had to explain what Seborga was, of course). Although I was unable to see my telephone interlocutors' faces, from the tone of their voices it was easy to imagine their eyebrows climbing up their foreheads. But let us not forget: had someone tried to ask the same question in Croatia, Estonia or Chechnya just a couple of years ago, the surprise would have proba- bly been much stronger, and the official eyebrows would have ended somewhere near the crown of the head. Yet all these republics (and many many more) are full- scale sovereign (or semi-sovereign) states at present.

It is here that the nightmare starts, and the much-publicised 'new European home' collapses like a house of cards. This was what Giorgio Carbone meant by having a bomb up his sleeve. Seborga syndrome may prove infectious in the not so distant future.

'We are the world's oldest constitutional monarchy, and Italy is only a hundred and thirty-three years old,' he says. 'We have nothing to do with Italy, and there's not a single document in existence that proves otherwise — this is a historical reality. So why should we keep paying taxes to a for- eign power? Our citizens want to work for the benefit of Seborga, not Italy.'

They do indeed. For the duration of his reign Giorgio Carbone has managed to win overwhehning support among the villagers (last year they conclusively voted for Sebor- ga's new constitution) and lured into his camp several neighbouring communes. The Seborgans look at their Prince with admira- tion, hoping he is capable of saving them from multiple problems and the unending political scandals of Italy. Indeed, the exam- ples of Monaco, Liechtenstein, San Marino and other flourishing European mini-states look encouraging. The Prince is vehemently certain that Seborga can do equally well exporting flowers, hosting tourists and even becoming a tax haven in due course . . .

'No one can force us to abandon our sovereignty, because it was obtained by con- stitutional means,' says His Highness Prince Giorgio I.

The Italian government has so far been ignoring events in Seborga. But it won't be able to do so for much longer: Prince Gior- gio I is busy appointing ambassadors. He's already got one in Andorra.

Vitali Vitaliev's book Little Is the Light: Nostalgic Travels In the Mini-states of Europe is published this month by Simon & Schuster.

Previous page

Previous page