Exhibitions

David Bomberg (Bernard Jacobson, till 18 January)

Seasonal stars

Giles Auty

In a year which began unpromisingly for me last January with Marxist hero Rod- chenko on display at the Serpentine and the awful British Art Show 1990 at the reopened McLellan Galleries in Glasgow, it is a relief to finish on a high note. The exhibitions of paintings and drawings by Sheila Fell at the Royal Academy and of David Bomberg at Bernard Jacobson (14A Clifford Street, W1) restore one's battered faith in the activities of artists. For me the pinnacles of 1990 were unquestionably Velazquez in Madrid in February and Van Gogh in Amsterdam and Otterlo in May. Clearly both were artists of the very highest distinction yet I feel their shades would look with some approval, at least, on the works of Fell and Bomberg. Fell drew inspiration unquestionably from the humanity of Van Gogh's vision: her

potato-pickers, turnip-gatherers and rich explorations of wintry landscape pay hom- age to the Dutchman's own early works from a northerly environment. Velazquez, in turn, might have admired the freedom of Bamberg's painterly response to Spanish terrain and to the great buildings of Ron- da, Cuenca and Toledo.

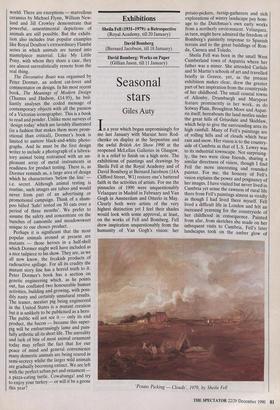

Sheila Fell was born in the small West Cumberland town of Aspatria where her father was a miner. She attended Carlisle and St Martin's schools of art and travelled briefly in Greece, yet, as the present exhibition makes clear, drew the greater part of her inspiration from the countryside of her childhood. The small coastal towns of Allonby, Drumburgh and Maryport feature prominently in her work, as do Solway Plain, Broughton Moor and Aspat- ria itself; hereabouts the land nestles under the great hills of Grisedale and Skiddaw, which help to give the surrounding area its high rainfall. Many of Fell's paintings are of rolling hills and of clouds which bear rain and snow. Her vision is to the country- side of Cumbria as that of L.S. Lowry was to its industrial townscape. Not surprising- ly, the two were close friends, sharing a similar directness of vision, though I find Fell the more interesting and rounded painter. For me, the honesty of Fell's vision explains the power and poignancy of her images. I have visited but never lived in Cumbria yet sense the rawness of rural life there from Fell's paintings almost as vividly as though I had lived there myself. Fell lived a difficult life in London and felt an increased yearning for the countryside of her childhood in consequence. Painted from afar, from sketches she made on her infrequent visits to Cumbria, Fell's later landscapes took on the amber glow of 'Potato Picking — Clouds', 1979, by Sheila Fell reassuring memories. Cumbria was her land of childhood certainties; there seemed little in her later life which she could trust so well.

David Bomberg was born 100 years ago in Birmingham, dying in artistic obscurity in London some 67 years later. The neglect of Bomberg's talents coincided, unfortu- nately for him, with that nadir in Western aesthetic sensibility known otherwise as the heyday of modernist hegemony. Bom- berg belonged briefly to the artistic avant- garde but the trauma of his experiences in the trenches during the first world war changed him forever. In short, the natural organic world from which many of his friends made involuntary and premature departures became more valuable to Bom- berg as a consequence. His disavowal of modernist orthodoxy and adoption of the Northern romantic tradition exemplified by artists as disparate as Turner and Van Gogh was an act of honesty for which Bomberg paid a painful and unjust price In the past 20 years his talents have been reassessed and admired increasingly due, not least, to a marked shift in the critical climate away from the stultifying canons of of modernist formalism. Bomberg has come to be recognised rightly as a 20th- century artist of foremost distinction, a more rounded and richer painter than either of his two followers Auerbach and Kossoff who have harvested fame and fortune from land which Bomberg broke.

Bomberg rediscovered the force of land- scape first in Palestine, then in Spain and Cyprus and even latterly in the countryside of the land which spurned his talent. In years to come I believe we will place Bomberg even higher in the hierarchy of 20th-century British artists. His paintings have become quite expensive now although they were never so during the artist's lifetime. However, those seeking to add a drawing to their collection can choose from a very wide selection of Bomberg's works on paper at Gillian Jason Gallery (40 Inverness Street, NW1).

With the onset of 1991 I would like to thank the readers who have sent me such an interesting and varied postbag in 1990; such contributions will help keep me on my toes during the coming year.

Previous page

Previous page