Shooting both friends and enemies

Bruce Bernard

UNREASONABLE BEHAVIOUR by Don McCullin Cape, £14.95, pp.288 The men, women and children, mostly in wretched and often disastrous situations, who Don McCullin has been photo- graphing since the mid-Fifties seem to look at his camera, when they can, not so much with any liking for the dour but purposeful and soldier-like figure who is pointing it at them, but more with respect for someone who is engaged in a serious and therefore permissible business. That is unless it is someone like the desperate woman (on page 264) who has just lost her entire family and can be seen about to launch a furious physical attack on him a few minutes before she herself was killed by an Israeli bomb in Beirut.

He is probably the greatest photo- grapher of war and human calamity who has ever lived, for what that is worth, and his other work, though lacking the charge generated by his complex reactions when faced by human ruthlessness or misery, shows him to be a photographic artist of a high order. The autobiography he has written, with just the right amount of help from Lew Chester, is shocking, moving and suspenseful, though, as one would expect, it never quite lays bare the source of the 'unreasonable behaviour' of the title.

Those who were not alive at the time cannot imagine quite what working class children looked and felt like during the late Thirties and the second world war (they were a different and unrecorded colour among other things). McCullin, from a family whose father was often too ill to work, leaving his mother mostly to pro- vide, could not have looked or felt very healthy at all while learning toughness. His two most significant memories are of his father's poor health, and life as an eva- cuee, brutally separated from his sister when she was taken into a comfortable middle-class home while he remained in a council house with worse to follow. He felt as if he were the 'wrong breed of dog'. His father is the person he expresses most warmth towards in the book, apart from his wife, though he later feels an almost equal affection for the inimitable Norman Lewis, several photographers' favourite father figure and travelling companion.

McCullin's account of his evacuation, his involvement with apprentice villains in Finsbury Park and his escape from the downward path via the RAF and photogra- phy is graphic and convincing. And his confession that he had 'no burning desire to be a photographer' even after he had proved himself one, and that his career was only saved by his mother getting his camera out of pawn at a critical moment, show how uncertain the beginnings can be of lives that later seem so firmly predes- tined. He evokes an unexpected image of the young McCullin enraptured by flowers seen through Moyses Stevens' waterfall windows in Berkeley Square, which re- minds one of his eye for 'the beautiful', a thread which runs in and out of his work, however brutal the subject-matter. He told me, when I worked on the Sunday Times Magazine, that he would have liked to have been a painter of the Italian Renaiss- ance, and I'm sure he meant it. But perhaps he would have been more of a Northern artist and his greatest master- piece a Deposition.

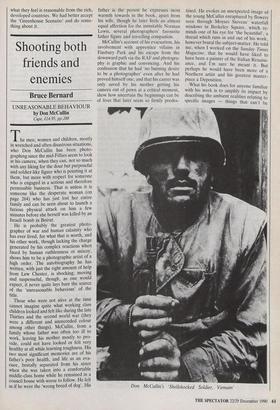

What his book does for anyone familiar with his work is to amplify its impact by describing the ambient realities relating to specific images — things that can't be Don McCullin's `Shellshocked Soldier, Vietnam' caught from one angle in a fraction of a second. After reading about an Albino Biafran boy he photographed I will never be able to think of him as just another shattered child again. It seems a pity, indeed, that more of McCullin's words were not used when the stories were originally published. But his work, if it is the best, as I think it is, may not have been the most influential in arousing public antagonism to the Vietnam war, for inst ance. His friend and rival for the highest photographic honours, Philip Jones- Griffiths, may have been more effective with his book Vietnam Inc. , which was pictorially more dispassionate and deliber- ately hostile to the American intervention. And Eddie Adams may have had more effect than the entire output of both of them with his famous picture of the Viet- cong prisoner being murdered by the Saigon police chief, of which he said, 'I made the picture by mistake. Any idiot could have taken it'.

McCullin's descriptions of personal pre- dicaments, like his imprisonment in Kam- pala and numerous other extremely 'hairy' situations, are horribly gripping and his confessions of his own often intense fear are only too credible. He must have seen more of war than any soldier, or indeed than any nurse or doctor who, after all, are confined mainly to sanguinary close-ups. And I would guess he has seen much more than any other photographer.

The compulsion to return to the killing fields again and again, seeming in the end more like a helpless addiction, at last began to fade, and left him, physically at least, relatively unscathed. As one who suffered acute anxiety after intervening with the editor of the Sunday Times Magazine and having him sent to the first explosion of Beirut in 1976, I could only feel relief when the British army author- ities prevented him from getting to the Falklands, where, who knows, an Exocet or a bullet might have been waiting for him.

But the book ends on a harrowing note that has nothing to do with war. His wife Christine's death from a brain tumour on their son's wedding day, and some time after Don had left her for someone else, makes very sad reading. I only met her two or three times, but felt, as I believe everyone else did, that there was some special kind of grace in her — which Don was certainly more aware of than anyone. But he has come through, after having, in John le Carre's phrase, tested 'his Maker's indulgence' to near destruction. I would like to see him now surpass his 19th- century Crimean War rival, Roger Fenton, as a photographer of landscape, still life and non-combatant unoppressed human- ity. He has shown promise of doing so.

All Don McCullin's admirers should read this book. It adds a substance that then seems indispensable to these stunning images.

Previous page

Previous page