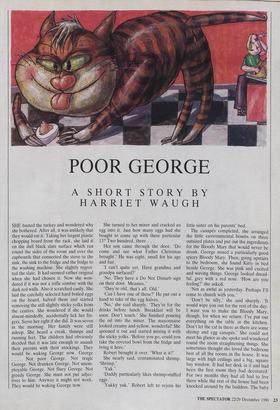

POOR GEORGE

A SHORT STORY BY HARRIET WAUGH

SHE basted the turkey and wondered why she bothered. After all, it was unlikely that they would eat it. Taking her largest plastic chopping board from the rack, she laid it on the dull black slate surface which ran round the sides of the room and over the cupboards that connected the stove to the sink, the sink to the fridge and the fridge to the washing machine. She slightly regret- ted the slate. It had seemed rather original when she had chosen it. Now she won- dered if it was not a trifle sombre with the dark red walls. Also it scratched easily. She laid the carefully selected hard boiled eggs on the board, halved them and started removing the still slightly sticky yolks from the centres. She wondered if she would absent-mindedly, accidentally lick her fin- gers. Serve her right if she did. It was seven in the morning. Her family were still asleep. She heard a creak, thumps and running feet. The children had obviously decided that it was late enough to assault their parents with their stockings. They would be waking George now. George . . . . Not poor George. Not tragic George. Not drunken George. Not unem- ployable George. Not fluey George. Not greedy George. She must not put adjec- tives to him. Anyway it might not work. They would be waking George now. She turned to her mixer and cracked an egg into it. Just how many eggs had she bought to come up with these particular 13? Two hundred, three . . .

Her son came through the door. `Do come and see what Father Christmas brought.' He was eight, small for his age and fair.

I can't quite yet. Have grandma and grandpa surfaced?'

`No. They have a Do Not Disturb sign on their door. Meanies.'

`They're old, that's all. Old.'

'Can I have one of those?' He put out a hand to take of the egg halves.

`No,' she said sharply. `They're for the drinks before lunch. Breakfast will be soon. Don't touch.' She finished pouring the oil into the mixer. The mayonnaise looked creamy and yellow, wonderful! She spooned it out and started mixing it with the sticky yolks. `Before you go, could you take the covered bowl from the fridge and bring it here.'

Robert brought it over. 'What is it?' She nearly said, contaminated shrimp. `Shrimp.'

'Yuk.'

`Daddy particularly likes shrimp-stuffed eggs.'

`Yukky yuk.' Robert left to rejoin his little sister on his parents' bed.

The canapes completed, she arranged the little environmental bombs on three outsized plates and put out the ingredients for the Bloody Mary that would never be drunk. George mixed a particularly good spicey Bloody Mary. Then, going upstairs to the bedroom, she found Kitty in bed beside George. She was pink and excited and waving things. George looked dread- ful, grey with a red nose. `How are you feeling?' she asked.

`Not as awful as yesterday. Perhaps I'll come to church with you.'

`Don't be silly,' she said sharply. `It would wipe you out for the rest of the day. I want you to make the Bloody Mary, though, for when we return. I've put out everything on the table in the kitchen. Don't let the cat in there as there are some shrimp and egg canapes.' She could not meet his glance as she spoke and wandered round the room straightening things. She sometimes thought she loved the bedroom best of all the rooms in the house. It was large with high ceilings and a big, square bay window. It had her desk in it and had been the first room they had decorated. For two months they had all had to live there while the rest of the house had been knocked around by the builders. The baby had howled, Robert had been a nuisance and the Italian au pair had by turns been belligerent and homesick. Was that when she had stopped loving, really loving George? Or was it when the business collapsed? Not that she hated him, it was more a suspension of feeling. If everything were miraculously to come right again she could imagine his image shifting, just a little, and reassembling to her gaze much as before. Men were no good at coping with failure and women were no good at coping with men's failure, or at least she wasn't. The proof of that was in the canapes, ha ha. She sat on the bed and the children showed her what she had wrapped up for them the night before. 'Goodness,' she said, 'What fun,' and, 'Show me how it works.' George took her hand. She wished he wouldn't. 'Breakfast,' she said. `I'll bring you yours in bed,' and, getting up, led the way downstairs.

They had bought the house two years ago. It had been irresistible. Much too expensive, of course, but who could have foretold the scarifying rise in mortgage rates, and the collapse of the property market leading to the squeeze on George's small chain of three estate agencies which she had helped set up? What was there in the mortar and brick of a house that could lead perfectly sensible people to destruc- tion? How many council-house owners were facing repossession? Why had she and George not remembered the salutary tale of the building of Blenheim? And where had Cardinal Wolsey's overweening ambition for Hampton Court led? Mrs Thatcher, what did you do by presenting home ownership as next to godliness? Thou shalt not have false gods before me. Well she did and that was that.

The children hardly needed any break- fast as they had already gorged themselves on sweets from their stockings. She heard herself saying, 'No more sweets until after lunch or you won't be able to eat the turkey,' even though it seemed very un- likely that the poor things would have any lunch. Would the experience scar them for life? Next year would they choke on their turkey? Would she? Oh dear! Poor George. There. She'd said it.

Her parents came in for breakfast as she and the children were finishing. They were dressed for church. Her mother's comfort- ably plump frame was encased in a black and white dog-toothed suit and she wore sensible shoes and a hat.

`Happy Christmas,' they said, going round the table and giving their daughter and grandchildren hugs and kisses.

`How's George?' her mother asked.

`He says better than yesterday, but he still looks pretty ropy. He's getting up for lunch, though.' She got up from the table and poured her parents some coffee.

`Good. Poor George.'

`While you have breakfast we had better get dressed. We'll be leaving at quarter-to- nine.'

As she dressed Kitty, Robert com- plained, 'Why should we go to church? I want to open my presents.'

`Your grandparents always go to church on Christmas day.'

`I don't see why we should, it's boring.' `It wouldn't be Christmas for them unless we went too. Don't be selfish.'

By quarter-to-nine they were all ready and neatly attired. Kitty had on white socks, a Liberty-print smock dress and a blue ribbon in. her fair hair. She looked sweet. Her mother told Robert to go upstairs and remind his father to make the Bloody Mary. 'Tell him there is extra coffee on the stove if he wants a second cup and to mind the cat.' That will fetch him, she thought. He's bound to come down to the kitchen now. Robert returned and and said that his father promised to make the Bloody Mary.

The church, which was the nearest to their Fulham house, was impressively full. Thick garlands of holly adorned the rood- screen and everyone was in hearty voice. Kitty held her hand and jumped on and off the kneeler. He mind, like Kitty's, was not on the service. She saw poor George putting on his dressing-gown and slippers and going downstairs for his second cup of coffee before he had his bath. She saw him eyeing the stuffed eggs. However ill he felt he would be unable to resist them; he was so helplessly greedy. He would decide that if he took one from each plate there would still be plenty to have with the Bloody Mary and then he would take another. In all he would probably take five.

0 star of wonder, star of night! Star with royal beauty bright, Westward leading still proceeding Guide us to they perfect light, she sang. Her hand holding Kitty's hand sweated. Afterwards, to Robert's frustration, as he wished to get back home and open presents, she took an unconscionable time talking to people, even introducing his grandparents to complete strangers. In the end they were practically the last to leave and the time was nearly 11 o'clock. 'I have just one or two stop-offs on the way home to give presents to some friends of Robert's and Kitty's. It won't take a moment, and then we'll go back and open our presents and have a drink,' she said.

Robert could hardly bear it. Never had Christmas been like this. His mother in- sisted that they all get out of the car at each stop and ring the bell together. The con- versations were endless. They were even invited in once, and his grandparents and mother drank cherry brandy while he had to watch his friend David, whom he hated, opening presents. How could she do this to him!

It was a quarter-to-one when they finally arrived home. 'We won't be eating until after two,' his mother reassured Robert. `There will be plenty of time to open presents first. Don't disturb daddy. The longer he has to rest before lunch the better.' She went downstairs to the kitchen and looked at the three plates of shrimp- stuffed eggs. Although rearranged, five canapes were missing. An uncomfortable prickly heat broke out over her. She sweated. 'Puss, puss,' she called. She gave the cat two canapes. How could she? She loved the cat. Its golden eyes begged for more as it twisted around her ankles. Keeping back three — the police would need some for analysis — she put the rest down the waste-disposal unit. She then turned her mind to cooking. She basted the turkey — it was beginning to look quite cooked — and rolled the potatoes in the juices and left them to roast. Collecting the Bloody Mary from the fridge, where George had left it, she went upstairs to the sitting-room.

'George let the cat into the kitchen and so we have no canapes but here is the Bloody Mary.' She felt dreadful. Her hands were now chilly and nerveless. She thought of George somewhere upstairs lying in his vomit, conscious, unconscious, contorted in agony. He had not called out. Her children tore at the paper round their presents. She sat on the sofa, the Bloody Mary, which was particularly spicy — George's 'flu must have blunted his taste-buds — her head turning from one child to the other and then to her parents. It was the law's fault she decided. If only George had not explained so carefully, when they had signed the mortgage agree- ment and the life insurance policies that went with it, that if anything should hap- pen to either of them, the survivor and the children would be safe, as she would inherit the house free of its mortgage. It had not been important then. Now, howev- er, that George was unemployed and going to default on the mortgage repayments, the house would be repossessed and sold, possibly at an overall loss. She had thought of divorce but although together they had little, apart they would have nothing. Surely her duty was to her children and their future? After all, their lives would not be enhanced by poverty and life in a one-bedroom flat somewhere. Nor would hers.

She looked around the sitting-room. It was so pretty, warm and satisfying. Although they did need a beautiful hang- ing lamp for the large rose in the middle of the ceiling. She must not think about that now, she reminded herself. It was for the future. Her stomach muscles tightened as she got up. 'Lunch, I think. If mummy and the children could help me get the food on the table, could you call George, daddy?'

'I'll go,' Robert shouted, running to the door.

'No,' she said sharply. 'You must help me. Daddy will go.' They were all downstairs when her father called.

'I think something must have happened,' he shouted. 'The bathroom door is locked and I can hear George groaning inside.'

She pounded upstairs followed by Robert and then more slowly by her mother. She rattled the bathroom door handle. 'George, George.' She called.

George groaned. 'What shall we do?' She turned to her father.

'Have you got another key?'

'No.'

'Oh dear.'

'We had better call the police,' her mother said.

'Oh dear,' she said.

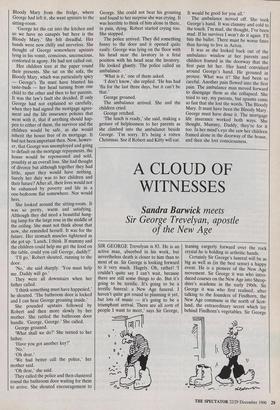

They called the police and then clustered round the bathroom door waiting for them to arrive. She shouted encouragement to George. She could not bear his groaning and found to her surprise she was crying. It was horrible to think of him alone in there, in pain, dying. Robert started crying too. She stopped.

The police arrived. They did something funny to the door and it opened quite easily. George was lying on the floor with his head near the lavatory in a fetal position with his head near the lavatory. He looked ghastly. The police called an ambulance.

`What is it,' one of them asked.

'I don't know,' she replied. 'He has had 'flu for the last three days, but it can't be that.'

George groaned.

The ambulance arrived. She and the children cried.

George retched.

'The lunch is ready,' she said, making a gesture of helplessness to her parents as she climbed into the ambulance beside George. 'I'm sorry. It's being a rotten Christmas. See if Robert and Kitty will eat. It would be good for you all.'

The ambulance moved off. She took George's hand. It was clammy and cold to the touch. I'm mad, she thought, I've been mad. If he survives I won't do it again. I'll bite the bullet. There must be worse fates than having to live in Acton.

It was as she looked back out of the ambulance window at her parents and children framed in the doorway that the first pain hit her. Her hand convulsed around George's hand. He groaned in protest. What was it? She had been so careful. Another pain flowed into the first pain. The ambulance man moved forward to disengage them as she collapsed. She tried to say, my parents, but spasms came so fast that she lost the words. The Bloody Mary. It must have been the Bloody Mary. George must have done it. The mortgage life insurance worked both ways. She thought, Mummy, Daddy, they're for it too. In her mind's eye she saw her children framed alone in the doorway of the house, and then she lost consciousness.

Previous page

Previous page