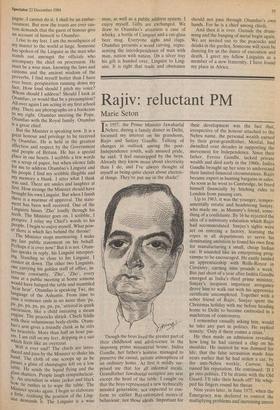

The Linguist

Stephen Lamport

The new diplomacy is more commonplace and prosaic than we imagine. But here and there the new and the old worlds of the diplomat mingle. Here is one example, aris- ing from a visit to Ghana earlier this year by Foreign Office Minister Malcolm Rifkind, who took the time to travel up-country to pay his respects to the King of the Ashanti in his tribal capital of Kumasi. This is how the visit appeared to his Private Secretary.

Thad expected a settlement of wooden /huts, set in a large circle in the dust of the grasslands, one but bigger and grander than the rest to house the Chief and his' family. But gold is wealth. And the Chief holds court in a dilapidated, crumbling town, a spread-out, decaying town, where tered and padlocked on a Sunday morning.

This is a town of messages. By the huge open market we pass God's Own Watch Company. The single-decker buses tell us `Don't ask what tomorrow beckons'. A Pentecostalist under an awning harangues a group of citizens, his voice crudely ampli- fied by a public address system. At a roundabout a cow stands in the road un- moved by the cars which sweep round her scattering the red dust.

The palace is not a but after all. The Paramount Chief of the Ashanti presides over his subjects in a modern, concrete guest-houst, two stories of modernity hous- ing the old Africa of the tribes. We arrive to drums and the flat metallic ring of wood striking metal. We have been told there will be time to collect our thoughts. There is much formal ritual to be worried over, and the Otumfuo's Private Secretary will explain what we should expect. Instead there is utter confusion as events refuse to unfold as they have been promised.

A majestic and enormous figure swathed in a large piece of cloth, orange, green,

yellow and red, emerges from the Palace and comes down the steps beneath an enormous umbrella; smiling, welcoming. Do we respond? Is this Otumfuo? Do we wait for a signal? Dare we approach him, risking the breach of some fundamental code of politeness? Otumfuo smiles again, so we rush up to shake his enormous hand. Everyone is suddenly doing the same. There is no order of precedence. We just force our way through. He has a warm, dry hand. We greet his wife, and his 'mother', old, a little wrinkled, dark black with a skin scrubbed and polished and shining, a twinkle in her eyes. Little is said. Are we allowed to speak? We have been told of the protocol. Otumfuo speaks to no man direct in public except his Linguist. It is the Linguist who speaks to the common herd, because Otumfuo can say no wrong, can never be mistaken. Only those who relay his words to the people can be found to be in error.

Otumfuo returns up the steps into the house and his audience chamber. There is a rush after him, like a football crowd swarming into the stadium when the gate opens. Otumfuo sits on a gold throne.

Around him in a square are sofas and chairs, French style. The Minister sits at his right, across the corner of the square. What about me? Suddenly I am told that I must be his Linguist, so that we pay Otum- fuo sufficient and worthy honour. We had joked about this on our way up from the city. Yes, I would be happy to translate from English into. English. Now I am not so sure. Above the bustle and the hubbub of people finding their places peacocks in the garden shriek and screech. Please sit. No, not there. Please sit. A chair is found and I sit beside the Minister and Otumfuo's three Linguists, the four interpreters of wisdom separating the paramount chief from his guest.

For a time there is no conversation. But the noise continues. Otumfuo looks majes- tic, smiling at his guests and his people, his great dark brown body covered in colour and in gold. On a finger of each hand sits a gold ring bearing a gold porcupine, the size of a baby's hand. Just as when the pro- cupine loses a quill another grows in its place, so when an Ashanti warrior falls in battle there is always another to take his place. Six gold bands cover an enormous arm. Whenever Ofumfuo moves they clank and clatter. A gold chain lies diagonally across his chest. He is a great chief, sitting flanked by his lesser chiefs.

Otumfuo read law in England as a young man. He was called to the Bar. He has been a diplomat. He knows London well. It cannot be true. Yet this is majesty and pomp, genuine and unaffected, not mimic- ry and pretence. Otumfuo is holding court in his palace, proudly, greeting his guest before his people, over whom he has the power of life and death. A ceremony as old as the Ashanti. The Linguist beside ale answers my question and shows me °tuna' fuo's speech. It is written in English. It is still not clear how we are to proceed. And the heat is growing in the audience room where there are no fans, only will' dows open at the far end, giving on to the peacocks shrieking in the garden outside. In white coat and black bow tie a man brings in a drinks trolley, laden with spirits and bottles of champagne. Glasses are put round and filled. We drink a toast, which Otumfuo proposes through his Linguist. MY throat is feeling dry, despite the chant- pagne. I cannot do it. I shall be an embar- rassment. But now the toasts are over cus- tom demands that the guest of honour give an account of himself to Otumfuo.

I rise to my feet. I am the mouthpiece of my master to the world at large. Someone has spoken.of the Linguist as the man who stands out amongst the officials who accompany the chief on procession. He must be a wise man, knowing the laws and customs and the ancient wisdom of the proverbs. I find myself hotter than I have ever been, perspiration running down my face. How loud should I pitch my voice? Whom should I address? Should I look at Otumfuo, or would that be a presumption? All over again I am acting in my first school play. There are photographs on a bookcase

to- my right. Otumfuo meeting the Pope. Otumfuo with the Royal family. Otumfuo is a great chief.

But the Minister is speaking now. It is a great honour and privilege to be received by Otumfuo. He is held in the greatest affection and respect by the Government and people of Britain. He has a special place in our heart's. I scribble a few words on a scrap of paper, but when silence falls for me to address Otumfuo's Linguist and his people I find my scribble illegible and my memory a blank. I utter what I think was said. There are smiles and laughter at first. How strange the Minister should have brought his own Linguist. But when I finish there is a murmur of approval. The state- ment has been well received. One of the Linguists hisses `Zho' loudly through his teeth. The Minister goes on. I scribble, I perspire. I relay my Chiefs words to his people. I begin to enjoy myself. What pow- er there is which lies behind the throne!

The Minister stops murmuring. I make my last public statement on his behalf. Perhaps it is over now? But it is not. Otum- fuo speaks in reply, his Linguist interpret- ing. Standing so close to his Linguist, I cannot sit down. The other two Linguists, one carrying his golden staff of office, in- tervene constantly, 'Zho', `Zho', every time at a public meeting at home somone would have bahged the table and mumbled 'hear hear'. Otumfuo is speaking Twi, the language of the Ashantis. From time to time a sentence ends in no more than 'pa, Pa, pa, pa, pa, pa, pa, pa,' uttered in quick succession, like a child imitating a steam engine. The peacocks shriek. Chiefs fiddle with their voluminous body-cloths. Otum- fuo's arm gives a friendly clank as he stirs his bracelets. More than half an hour pas- ses. I am still on my feet, dripping in a suit which feels like an overcoat. Will it ever end? The chiefs are intro- duced and pass by the Minister to shake his. hand. The cloth of one scoops up as he Passes a glass of champagne left on a low table. He sends the liquid flying and the glass shatters. People laugh sympathetical- ly. An attendant in white jacket and black Dm tie rushes in to wipe the table. The Minister speaks again. I begin to elaborate a little, realising the position of the Ling- uist demands it. The Linguist is a wise

man, as well as a public address system. I enjoy myself. Gifts are exchanged. We draw to Otumfuo's attention a case of whisky, a bottle of Campari and a cut-glass beer mug. Everyone sighs and claps. Otumfuo presents a wood carving, repre- senting the interdependence of man with man, nation with nation. On a silver tray his gift is handed over, Linguist to Ling- uist. It is right that trade and obeisance should not pass through Otumfuo's own hands. For he is a chief among chiefs.

And then it is over. Outside the drum- ming and the banging of metal begin again. We are invited out to the peacocks and drinks in the gardeg. Someone will soon be dancing for us the dance of execution and death. I greet my fellow Linguists as a member of a new fraternity. I have found my place in Africa. ,

Previous page

Previous page