THEIR COUNTRY NEEDS THEM

Stephen Schwartz on how a disturbing encounter with

a ruthless Albanian family in Kosovo convinced him that most of the refugees should be sent home

FIRST, some disclaimers: I am a journalist, and have reported from the Balkans, but I do not pretend to be neutral. Objective, yes, meaning as fair and accurate as I can possibly be. But neutral, no. I believe Slo- bodan Milosevic and Serbian expansionism represent overwhelmingly evil forces; I believe the Kosovar Albanians are victims. And I wholeheartedly believe it was right and proper for Nato to intervene in Koso- vo. All that said, and having just come from a trip to Kosovo, I do not sympathise with Kosovar Albanians who claim asylum in foreign countries.

To explain myself fully, I must tell a personal story. In May 1999, with the Kosovo war underway, I met an Alba- nian refugee family, headed by a middle-aged man I shall call Midhat. He had worked as a mechanic in Kosovo and spoke good English. He had a nice family, consisting of him, his mother, his quite attractive wife, and their three teenaged children, two girls and a boy.

I met them in a refugee camp in the Balkans as I walked along a set of tents asking, in Albanian, for an English speaker. I was accompanied by an American col- league and was looking for someone who could be interviewed by her without my having to be there as an interpreter.

We came into the tent with Midhat and his family and were offered coffee, cigarettes and food. Our conversation was warm, especially when I showed I could speak Albanian and knew Albanian history. I did not feel particularly offended or cau- tious when, after several hours, Midhat's wife said, in what I now realise was a some- what sniffy manner, that if I was so willing to be friendly to them I should help them go to America. I agreed at least to investi- gate the possibility since at that moment bombs were still falling and America was, indeed, taking in Kosovar refugees. But I specified that I would make no promises. I interviewed and photographed the family, reported on their situation for an Ameri- can magazine and looked into their reset- tlement. Then the war ended.

In August I went back to the Balkans fully expecting Midhat and his family to have gone home to Kosovo. I was surprised to find that, while the refugee camp was almost completely empty, they had remained in their tent. I went to see them, and found Midhat quite insistent that I should help him to get his family to the United States. I had, he said, made a promise; I had given him besa, the tradi- tional personal pledge of the Albanians.

I must say that this appeal affected me strongly and, although remaining in the Balkans myself, I made renewed efforts to find the family a place in the United States. Several initiatives with friends of mine there, including some Kosovar Albanians who had arrived years before, failed to work out. Finally, a US diplomat told me plainly that I was wasting my time; that the Kosovars no longer had anything to fear and should go home and reconstruct their lives. I told this to Midhat but his answer was simple. He had, he said, 'nothing to go home to in Kosovo'. His house had been destroyed and he claimed he had no oppor- tunities for work. He insisted that he want- ed to go to the United States and, if not there, to Germany. To some third country, in any event. I gave the only honourable answer I could imagine, which was to offer him work for me as a driver, translator and general assistant.

Nevertheless, Midhat acted as if we had gone to Kosovo not for me to do journalistic work, but for him to get his passports. Since he was afraid to stand in line for the document, why then, I should do it. In fact, according to him, I should go into the Serbian passport office and 'arrange things' for him.

Time went by and, while I was able to get some of my interviews done, others went by the board as, each day, we wasted hours watching the passport queue and arguing. I even went up to the British army guards at the queue — members of the excellent Royal Green Jackets — and inquired about the whole mess. That very day, two Albani- ans who had collected passports at the office were 'arrested' and beaten up by KLA goons.

The next day, the moment of truth came. We were standing and looking at the queue. still arguing over why we had come to Kosovo, when two nasty-looking customers suddenly appeared and asked me in Albani- an, 'Where are you from?' One of them had the requisite long scar down his cheek. America,' I said. 'I'm a journalist.' It was the right answer and they patted me on the shoulder and let us go. But that was the end of that. I wasn't about to risk my life further. We went our separate ways after I had dressed Midhat down, telling him that if he Was going to go to Germany or anywhere else it was his affair, not mine, and that I did not want to be further involved.

I went to stay in Sarajevo. A couple of months went by and Midhat and his family turned up there and he found me on the street. I didn't know what to say or do. I didn't feel threatened and I needed some- one to help me with Albanian research, so I offered him work again. But, still, that wasn't what he wanted. Now he asked me to go to the German Embassy in Sarajevo and make inquiries for him, which I refused to do. Occasionally I would meet him in cafés and he would suggest such gambits as stopping German soldiers on the street and asking them for help. I told him that respectable people in America and, for that matter, Germany, do not stop strangers, much less working journal- ists, on the street and ask for complicated forms of assistance. But he was impervi- ous to such logic. I had to help him, he said. I had promised. He brought his wife and then his children to my door to try to move me. I grew increasingly irritable about this but continued to try to find rea- sonable solutions.

I arranged through a Bosnian friend for Midhat to get a better job. He declined. He wanted me to call someone I knew in the German Embassy and make arrange- ments for him to go there. Again I said no. I came to another flashpoint with Midhat when, one day, I told him I was scheduled to meet a Dutch investigator of the Sre- brenica massacre. He insisted on coming with me. I told him he had no reason to be Involved in the encounter, which had noth- ing to do with Kosovo. His answer, rather self-righteous in tone, was that he intended to ask the war-crimes investigator to help get his family into the Netherlands. I blew up and told him to go to hell; that his sug- gestion was obscene.

By this time readers must consider me ridiculously naive and generous, but I am the grandchild of Jewish refugees, who fled to America illegally, and I really felt the onus was on me to be honourable. Of course, it wasn't, just as it isn't on the British. Again, I didn't see Midhat for a couple of months and, when I did, his wife had gone to Germany illegally. Now it was his children's turn and he had decided to try me again. This time I sat down and said, `Look, Midhat, I'm not going to try to help you any more. There isn't any provision for Albanians to go to Germany or the USA or anywhere else just because they want to.' `My kids are crying for their mother,' he said. 'Your kids are grown up. Your eldest daughter is 19 and looking for a husband. Grown kids don't cry for their mother. You've got to stop lying.' I said. 'Well, I'm going to the Germans and I'm not going to tell them I'm Albanian. I'll say I'm a gypsy fleeing the Albanians.'

I could go on and on with this story. It never came to a point where I had to threaten Midhat with the police or any other dire consequences, but his fund of scheming was inexhaustible. He had advised his wife in Germany to tell the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees that she did not know where he was, so she could collect a higher benefit. But UNHCR had registered them as a family in their first refugee camp and that datum showed up in a computer record. He had got inside the German Embassy in Sarajevo and, after being denied considera- tion, changed his story so many times in the progress of his interview that the embassy official finally told him to leave, that she was sick of him.

Midhat told me all this as if it was per- fectly normal. He wanted to get to a third country: if not Germany, then the Nether- lands; if not the Netherlands, Luxem- bourg. England did not appeal to him because he had always heard London was cold and foggy, but he did not want to go back to Kosovo. He would tramp the streets until he found someone he could take advantage of, who would give him what he wanted. Or he would pay for an illegal passage. I might have suspected he had some reason to fear going home, except that his relatives had welcomed him warmly back to Pristina. His motives were purely selfish: it did not matter that his wife would undergo various humilia- tions and might be expelled because of his lies; or that his grown children would have to learn a new language; or that an illegal transit might land him in a form of long- term debt that would endanger his family. He was single-minded. He wanted a new life away from Kosovo. He wasn't fleeing from anything. He just wanted more opportunities. But don't we all?

The moral of this story is simple. The United States, Nato and, for that matter, the Kosovo Liberation Army, did not put their lives on the line so that dissatisfied urban hicks from Pristina could collect social benefits in Britain or anywhere else as refugees. Albanians who love Kosovo belong in Kosovo, rebuilding their home- land. Britain should investigate every claim to asylum in the greatest possible detail and most, at least from Kosovar Albanians, should be rejected. If the British want to welcome the only Albanians who really have something to fear in Kosovo, i.e. the former collaborators with the Serb police, let the applicants at least be obliged to be honest about their motivations. And, by the way, about a million Albanians in Kosovo would agree with this.

Stephen Schwartz is the author of Kosovo: Background to a War, recently published by Anthem Press.

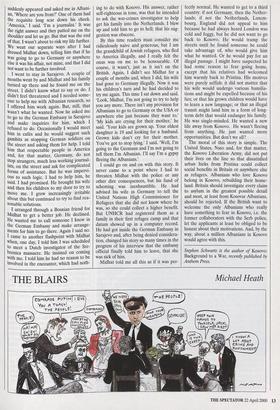

Previous page

Previous page