HIS PICNICS HOLD THEIR HORRORS

Travellers:

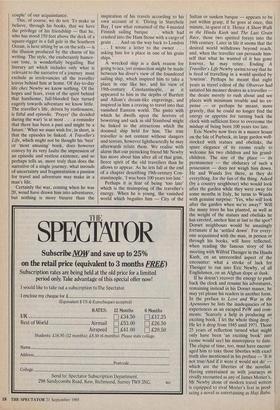

A profile of Eric Newby,

brilliant survivor of mishaps

IF, INSTEAD of finding ourselves in our usual seat on the Clapham omnibus, we armchair travellers were to be placed upon yaks riding into the Karakorams with a Hunza porter, two months' provisions, and instructions to make for Yarkand, no companion upon a neighbouring yak would be greeted with more delighted relief than the stalwart and eager figure of Eric Newby. 'Everyman, I will go with thee and be thy guide': to no travel writer's works is the epigraph of the Everyman Library a better fit.

For there is nothing in Eric Newby (as he projects his personality in his books) of that lonely, craggy singularity which is the repellent, if awe-inspiring, characteristic of `the great traveller'. Newby will not, we feel, keep striding ahead to reconnoitre mountain-tops, keep pushing us beyond our limit, keep pointing sternly to a further horizon for today's march than we can hope to attain. He seems to possess no specialised skills. Tough as he must be, it appears to be the kind of resilience which enables him to recover from mishap, rather than the horniness of carapace which is impervious to the ill-usage of hard travel. If he drinks water from a Persian brook, he is as ill as the rest of us would be, his toughness not preserving him from harm but enabling him to stagger onwards, though seriously harmed. The impression we have of a journey made in his company is not of an expedition, but of a picnic overtaken by misfortune. It is this expecta- tion he has of enjoying himself — the vigorous good-humour of his voice as we hear it in his narrative — his evident good-fellowship — which makes him a companion to be chosen above any traveller, past or present, if a real journey were to be made with any writer of books of travel.

The two books that first made his name, The Last Grain Race and A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush — one the account of a voyage in a square-rigger undertaken at 19, the other a journey into Nuristan made at 37 — are the narratives of two remarkable adyentures. Still, there have been adven- tures equally stirring recorded in books of travel: Newby's genius, above other travellers, is to select and delineate both his incidents and his dramatis personae so that each character and each event shapes and advances his narrative in so artistic a fashion that the satisfactory symmetry of fiction seems to be added to the vigour of truth. Take Hugh Carless, his companion in the Hindu Kush. Mr Carless is the very man a novelist might hope to invent to inflict upon Mr Newby in wild lands if an amusing book were to result. His preci- sion, his experience, his wariness, his preparations, all contrast wonderfully with Newby's slapdash methods. No caricature out of Stiff Upper Lip, he is yet very easily recognisable by Everyman as a diplomat, which enables us to flesh him out in our own minds, and imagine his responses even when they are not recorded. Dialogue between Carless and Newby never fails to distinguish the character of each more clearly, so that the contrasts and frictions of their relationship develop alongside the narrative. Newby asks: "What's a kro?" Carless: "One kro equals half an Iranian farsak." It was some time before I was able to pluck up courage to ask what an Iranian farsak was. "The distance a man travels over flat ground in an hour. And, quite frankly, I think you should have made more progress with your Persian by now." ' The dialogue — the art — is faultless. Or take an exchange in a cave in the Apen- nines between Newby and another escaped PoW, which refers to Newby's cough. ' "You should try to control yourself," he said severely one day when he was thor- oughly exasperated. "I do try," I said. "Do you think I enjoy it?" "I don't know," he said, and I felt like striking him.' It is scenes so human as these, where the landscape and the circumstances have squeezed the people together, which are a rarity in books of travel.

Dialogue in a book of travels (unless the writer has the total recall which Mr Newby specifically disclaims) must surely be art. With equal art Mr Newby makes sure that his actors — the fo'c'sle full of seamen in The Last Grain Race for example — do not outgrow the role required of them by dramatic narrative. He creates no Frank- enstein's monster which will hog the stage. The Captain of the Moshulu, like the seamen, is all he should be — all we half-remember from reading Marryat or Dana — but neither he nor anyone else in Mr Newby's books is so excessively origin- al a 'character' as to unbalance the narra- tive or to distract our attention from our chief interest in it, which is to listen to Mr Newby's account of his adventures and to watch our hero's character displayed in action. For it is always Newby we want more of — Newby we sympathise with Newby's cough, or feet, or dashed hopes, with which we suffer. Without one word of vanity in all his books, he emerges effort- lessly as the hero of them all.

As leading lady his wife, Wanda, plays a beautifully orchestrated part too. An indi- vidual of magnetism and resolution from her first appearance in Love and War in the Apennines, her progress towards a co- starring role is steady throughout succes- sive books: in A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush taken only as far as Tehran, she completes the voyage (though constantly threatening to `go back to my country and my people') in Slowly Down the Ganges, and is, in On the Shores of the Mediterranean, the writer's indispensable companion, their inseparability understood and admired by us quite as if we knew them as a 'devoted couple' of our acquaintance.

This, of course, we do not. To make us believe, through his books, that we have the privilege of his friendship — that he, who has stood 150 feet above the deck of a square-rigger in a full gale in the Southern Ocean, is here sitting by us on the sofa—is the illusion produced by the charm of his writing. The style, the exuberantly humor- ous tone, is wonderfully beguiling. But literary art which includes only what is relevant to the narrative of a journey must exclude as irrelevancies all the traveller leaves behind him at home. Of day-to-day life chez Newby we know nothing. Of the hopes and fears, even of the spirit behind that handsome, full-blooded face turned eagerly towards adventure we know little. The traveller's life, driven by restlessness, is fitful and episodic. 'Prayer' (he decided during the war) 'is at most . . . a reminder that there has been a past and might be a future.' What we must wish for, in short, is that the episodes be linked. A Traveller's Life, which might not be thought his 'best' or 'most amusing' book, does however convey by its very faults the impression of an episodic and restless existence, and so perhaps tells us, more truly than does the narrative of a single journey, what inroads of uncertainty and fragmentation a passion for travel and adventure may make in a man's life.

Certainly the war, coming when he was 20, woud have drawn him into adventures, but nothing is more bizarre than the inspiration of his travels according to his own account of it. 'Diving in Starehole Bay, I saw what remained of the 4-masted Finnish sailing barque . . . which had crashed into the Ham Stone with a cargo of grain . . . And on the way back to London . . . I wrote a letter to the owner . . . asking him for a place in one of his grain ships.'

A wrecked ship is a dark reason for going to sea, yet connection might be made between his diver's view of the foundered sailing ship, which inspired him to take a place in one like her, and his view of 19th-century Constantinople, as it appeared to him in the depths of Bartlett and Allom's dream-like engravings, and inspired in him a craving to travel into that vanished Eastern world. The gusto with which he dwells upon the horrors of bowstring and sack in old Stamboul might be linked to the attractions which the doomed ship held for him. The true traveller is not content without dangers and terrors, however lightheartedly he may afterwards relate them. We realise with alarm that our picnicking friend Mr Newby has more about him after all of that grim, fierce spirit of the old travellers than he allows to appear. As he lets fall at the end of a chapter describing 19th-century Con- stantinople, 'I was born 100 years too late.'

Perhaps it is fear of being `too late' which is the mainspring of the traveller's energy. When he is young, the vanished world which beguiles him — City of thd Sultan or sunken barque — appears to be just within grasp, if he goes at once, this minute, in quest of it. Hence A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush and The Last Grain Race, those two spirited forays into the 19th century. Later in life it seems that the desired world withdraws beyond reach, and, when the traveller can persuade him- self that what he wanted of it has gone forever, he may retire. Ending A Traveller's Life Newby seems to say that he is tired of travelling in a world spoiled by `tourism'. Perhaps he meant that eight years as travel editor of the Observer had satiated his meaner desires as a traveller the desire merely to rush about and see places with minimum trouble and no ex- pense — or perhaps he meant, more gravely, that he could no longer find the energy or appetite for turning back the clock with sufficient force to overcome the mishap of being born 100 years too late.

Eric Newby now lives in a manor house on the Isle of Purbeck, its large garden well- stocked with statues and obelisks, the spare elegance of its rooms ready to welcome his two children and his grand- children. The size of the place — its permanence — the obduracy of such a possession — does not weigh him down. He and Wanda live there, as they do everything, for the fun of the thing. Asked (by a country neighbour) who would look after the garden while they were away for some months in Italy, he turns to Wanda with genuine surprise: 'Yes, who will look after the garden when we're away?' Will the many trees he has planted, as well as the weight of the statues and obelisks he has erected, anchor him at last to the spot? Dorset neighbours would be amazingly fortunate if he 'settled down'. For every- one acquainted with the man, in person or through his books, will have reflected, when reading the famous story of his meeting with Wilfrid Thesiger in the Hindu Kush, on an unrecorded aspect of the encounter: what a stroke of luck for Thesiger to run into Eric Newby, of all Englishmen, on an Afghan slope at dusk.

If he doesn't recover the energy to push back the clock and resume his adventures, remaining instead in his Dorset manor, he may yet please his readers in another form. In the preface to Love and War in the Apennines he lists the inadequacies of his experiences as an escaped PoW and com- ments: 'Scarcely a help in producing an exciting book. I let the whole thing drop.' He let it drop from 1945 until 1971. Those 25 years of reflection turned what might only have been 'an exciting book' into (some would say) his masterpiece to date. The elapse of time, too, must have encour- aged him to take those liberties with exact truth also mentioned in his preface — 'It is not true/And if it were it would not do' which are the liberties of the novelist. Having entertained us with journeys as vividly recounted as any of James Morier's, Mr Newby alone of modern travel writers is equipped to rival Morier's feat in prod- ucing a novel as entertaining as Haji Baba.

Previous page

Previous page