NEW MODEL SPIES

Ronald Payne on the

seduction of Soviet agents by the values of the West

ONLY when a big event takes place is it possible for outsiders to peer under the cloak of espionage and get some idea about what is really going on in the private intelligence wars. The trumpeted arrival on -our side of Oleg Gordievsky, even the limited amount of information which comes to light, helps to show what has been happening to the KGB, the commit- tee of state security.

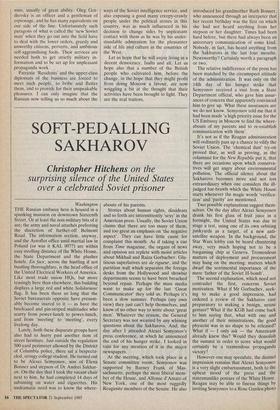

Take a look at the pictures of the man, for they provide a first clue. There he is in the kind of clothes which any well turned out man might wear, sometimes dressed for jogging, sometimes for diplomacy. Out is the baggy look, as a fashion writer might say. The Khrushchev style is nothing but nostalgia now.

The man responsible for that was the late Yuri Andropov, the KGB boss who fought his way to the highest pinnacles of the Kremlin. Although he himself had never even visited the West he did get the idea that by and large that mysterious area was populated by snappy dressers and that his boys ought to try not to stand out like sore Bolsheviks at a United Nations cock- tail party. In the words of an earlier defector: 'He knocked the rough edges off the KGB.'

What was much more important was the attention that Moscow Centre gave to improving the training of those of its operatives who were to be exposed to service in foreign parts. The language school smartened up and brought itself up to date with the way people talk in our part of the world. Instead of relying on rugged army officers and policemen they brought in bright young men from the creme de la creme of Soviet society educated at posh Moscow schools. The USSR still believes in elite institutions for suitable persons. Like Gordievsky, they proceed to pri- vileged higher education, and those who succeed are recruited for a KGB career which offers rich rewards, good living and travel abroad in the forbidden zones.

By chance I once met such a young Russian on a flight to Kiev who told me that he was a captain in the Red Army serving on the Chinese border. He quoted Kipling in admirable English, spoke of his duty to help the peasants there and gener- ally adopted the high-minded tone of a serious Indian army officer in the old days. Whereas his old British equivalent might have made stiff-lipped mention of God, he made a polite nod towards Marx, and said that he hoped later to go into the KGB. Dr Arnold would have been proud of such a man.

After attending one of the better univer- sities such young men are spotted by KGB professors and recruited to the service's own training centre in Moscow. Among other activities, they are positively encour- aged to read capitalist newspapers and literature, to steep themselves in films and plays which are carefully withheld from the horny-handed proletariat in the Soviet Union.

Does all this sound vaguely familiar? It should do for that is rather what used to happen in our own dear country. But in the mirror image our young men in the 1930s becames so fascinated by studying the progress of the great Soviet Revolution that they decided to join it, and so the great defectors, the Macleans and Philbys and Burgesses, were born. When the war started they replaced the old colonial policemen and far-flung officers who had run British military intelligence until then.

In Andropov's Russia the old Chekists of the Revolution died off or were thrust aside like our old colonials, the veterans were replaced by the bright young men, the sons of the party and military elite. Divorced from the realities of Soviet life on grounds of non-consummation, used to hard training and special living conditions, it is not surprising that they should become fascinated by the West. They were like young monks who occasionally became so fascinated by the enemy works of the Devil that they began to worship him. In the words of Prospero: 'I would all things by contraries execute.'

The Russians are now beginning to find themselves in the same position which embarrassed Britain formerly. Now it is their sharp intelligence operatives who are deciding that the other side is better and more likely to overcome its difficulties than the Marxist state in the East. The time of the Soviet defector of conscience is upon us.

Oleg Gordievsky is not the only KGB man subjected to a long stay in the West to decide that it really is rather more agree- able to live in the lands of plenty where you can say and do what you will. It does not mean that they believe everything Western is perfect, any more than an enthusiast for Moscow like Donald Maclean believed that everything was perfect in the Soviet Union — just better and improving.

Among the first of the Soviet intelli- gence officers to help the West because he felt that democracy was superior to com- munist tyranny was Colonel Oleg Penkov- sky, a defector from the GRU. A graduate of the Frunze military academy, he decided it was his duty to help thwart the dangerous tricks of Khrushchev.

Arkady Shevchenko, who went over to the Americans in New York, was a similar high flier in the foreign service in his forties. A protégé of the foreign minister, he also had an influential post at the United Nations. Another comparable Rus- sian who decided for the West was Stanis- las Levchenko, son of a Soviet general, schooled in Japanese and given a crash course in journalism before being de- spatched to Tokyo to recruit 'agents of influence'. Those agents of influence are considered very trendy these days by the KGB, which devotes a good deal of its attention to recruiting them in every coun- try. They are very useful for doing the dirty work of propaganda by undermining the loyalty of their compatriots under KGB guidance, in giving a helpful push to encourage class warfare, and lending a hand with trouble-making and sometimes intelligence-gathering.

It is important to remember that there is much more to being a Soviet agent than digging out the order of battle and photo- graphing the plans for the new Star Wars gadgets. They are also the undercover men in the dirty campaigns of propaganda to wrong-foot the West among its own people in the matter of terrorism and freedom fighting, defence and armament provision. In such enterprises they need the help of local citizens and it is the task of Residents abroad and their embassy back-up people to go out to meet and cultivate bankers and churchmen, trade union leaders and politi- cians. It comes as no surprise therefore that Gordievsky, the officer-class Russian, should have got along so well with the entourage of archbishops, and even the Revd Michael Bordeaux, a churchman who really does know his Soviet Union. He probably had much more trouble with such naive left-wing apologists as Ron Brown MP who rushed into print to say he had been sought out by the man from Moscow.

Such a cultivated person as Gordievsky, whether he had been a double agent or not, must have been amazed by the atti- tudes of some of the fellow-travelling politicians, do-gooders and union leaders who unquestioningly admire the Eastern bloc tyranny.

A real class system exists in every intelligence-gathering operation. Top of the pile are intelligence officers, well trained, analytical and questioning per- sons, usually of great ability. Oleg Gor- dievsky is an officer and a gentleman of espionage, and he has many equivalents on our side of the line. Unfortunately such paragons of what is called the 'new Soviet man' when they go out into the field have to deal with the lower orders, greedy and unworthy citizens, perverts, and ambitous self-aggrandising fools. Their services are needed both to get strictly military in- formation and to be set up for unpleasant propaganda work.

Patriotic 'Residents' and the upper-class diplomats of the business are forced to meet such people, to bribe and flatter them, and to provide for their unspeakable pleasures. I can only imagine that the Russian now telling us so much about the ways of the Soviet intelligence service, and also exposing a good many creepy-crawly people under the political stones in this country, was as much influenced in his decision to change sides by unpleasant contact with them as he was by his under- standable admiration for the pleasanter side of life and culture in the countries of the West.

Let us hope that he will enjoy living in a decent democracy, faults and all. Let us hope also that a number of the British people who cultivated him, before the change, in the hope that they might profit from doing Moscow a favour, are now wriggling a bit at the thought that their activities have been brought to light. They are the real traitors.

Previous page

Previous page