DON'T CALL ME CULTURED

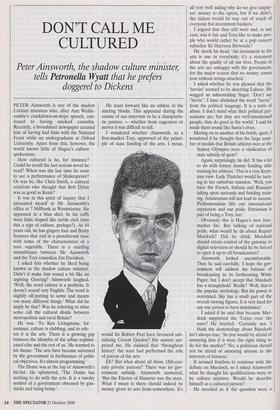

Peter Ainsworth, the shadow culture minister; doggerel to Dickens

PETER Ainsworth is one of the shadow Cabinet ministers who, after Ann Widde- combe's crackdown-on-dope speech, con- fessed to having smoked cannabis. Recently, a broadsheet newspaper accused him of having had links with the National Front while an undergraduate at Oxford University. Apart from this, however, the world knows little of Hague's culture spokesman.

How cultured is he, for instance? Could he recall the last serious novel he read? When was the last time he went to see a performance of Shakespeare? Or was he, like Chris Smith, a cultural relativist who thought that Bob Dylan was as good as Keats?

It was in this spirit of inquiry that I presented myself at Mr Ainsworth's office at 7 Millbank in Westminster. He appeared in a blue shirt. In his cuffs were links shaped like treble clefs (was this a sign of culture, perhaps?). At 44 years old, he has gingery hair and fleshy features that end in a protuberant nose with some of the characteristics of a root vegetable. There is a startling resemblance between Mr Ainsworth and the Tory comedian Jim Davidson.

I asked him whether he liked being known as the shadow culture minister. Didn't it make him sound a bit like an aspiring Goering? Ainsworth laughed. `Well, the word culture is a problem. It doesn't sound very English. The word is slightly off-putting to some and means too many different things.' What did he imply by that? Was he referring to what some call the cultural divide between metropolitan and rural Britain?

He was. `To Ken Livingstone, for instance, culture is clubbing, and to oth- ers it is the arts. There is a growing gap between the lifestyles of the urban sophisti- cated elite and the rest of us.' He warmed to his theme. The arts have become suborned by the government in furtherance of politi- cal objectives. It's almost programming.'

The Dome was at the top of Ainsworth's hit-list. He spluttered, The Dome has nothing to do with the arts. It is a tawdry symbol of a government obsessed by gim- micks and being bossy.' He leant forward like an athlete in the starting blocks. This appeared during the course of our interview to be a characteris- tic posture — whether from eagerness or nerves it was difficult to tell.

I wondered whether Ainsworth, as a free-market Tory, approved of the princi- ple of state funding of the arts. I mean, would Sir Robert Peel have favoured sub- sidising Covent Garden? His answer sur- prised me. He claimed that 'throughout history' the state had performed the role of patron of the arts.

Eh? But what about all those 18th-cen- tury private patrons? There was no gov- ernment subsidy. Ainsworth answered, `But the Elector of Hanover was the state. What I mean is there should indeed be money given to arts from somewhere. It's all very well asking why do we give taxpay- ers' money to the opera, but if we didn't, the tickets would be way out of reach of everyone but investment bankers.'

I argued that they still were and, in any case, was it fair and Tory-like to make peo- ple who would rather be at a pop concert subsidise Sir Harrison Birtwistle?

He shook his head. 'An investment in the arts is one in everybody; it's a statement about the quality of all our lives. People in the arts are unhappy with the government, for the major reason that no money comes now without strings attached.'

I asked whether he was pleased that the luwies' seemed to be deserting Labour. He wagged an admonishing finger. 'Don't say "luwie". I have abolished the word "luvvie" from the political language. It is a term of abuse. I don't mind what their political per- suasions are, but they are well-intentioned people, they do good in the world.' I said he made them sound like Santa's elves.

Moving on to another of his briefs, sport, I wondered if he thought that the large num- ber of medals that British athletes won at the Sydney Olympics were a vindication of state subsidy of sport?

Again, surprisingly, he did. 'It has a lot to do with lottery money funding elite training for athletes,' This is a very Keyn- sian view. Lady Thatcher would be turn- ing in her suburban mansion. 'Well, you have the French, Italians and Russians taking sport seriously and funding train- ing. Amateurism will not lead to success. Professionalism lifts our international reputation and our pride. Patriotism is part of being a Tory, too.'

Obviously this is Hague's new free- market lite. But talking of national pride, what would he do about Rupert Murdoch? Did he think Murdoch should retain control of the gateway to digital television or should he be forced to open it up to all broadcasters?

Ainsworth looked uncomfortable. Then he said carefully, hope the gov- ernment will address the balance of broadcasting in its forthcoming White Paper, but I don't accept that Murdoch has a stranglehold.' Really? 'Well, that is the popular mythology. But his power is overstated. Sky has a small part of the overall viewing figures. It is very hard for any one person to have dominance.'

I asked if he said that because Mur- doch supported the Tories over the euro? He bristled. 'Certainly not. I think the demonology about Murdoch isn't always true.' So you would be afraid of annoying him if it were the right thing to do for the market? 'No, a politician should not be afraid of annoying anyone in the interests of fairness.'

It seemed fruitless to continue with the debate on Murdoch, so I asked Ainsworth what he thought his qualifications were to be culture minister. Would he describe himself as a cultured person?

He recoiled as if the question were a snake. 'Good God, I wouldn't say that; no. I like to think I am educated. I read English at Oxford.'

What was the last opera you saw? He paused. 'I think it was the Rape of Lucrezia done by, erm, the, er, the National Youth Opera.' A bit of music was all very well, but what about the great canon of English literature? What was the last novel he had read. Ainsworth answered, 'Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.' What? Aren't you a bit old for that?

`No, anyway, before that I read a biogra- phy of Lord Byron by Benita Eisler.' OK, a children's book and a life of a rakish poet. Hadn't he read any of the classics? Ainsworth looked injured. 'Of course, I have read Jane Austen and Thomas Hardy and everything like that.'

Is Bob Dylan as good as Keats? 'No, cer- tainly not. That view, though, is implicit in the way this government is approaching the arts. I believe that most of the inspirational people in the arts lived in the past.'

Speaking of the past, you have been quoted as saying that your hero is Pitt the Younger. Do you see any similarities between yourself and Pitt?

Ainsworth blushed prettily. `No, I've left it too late for that. In any case, I would rather be Lord Byron.' I tell him he looks more like Jim Davidson. 'Oh. He won't thank you for that.'

Like Davidson, Ainsworth has had a brush or two with controversy, as when he recently admitted to having taken cannabis. As soon as I mention this, however, he shuts up like a clam. 'I'm not talking about that. Not a word.' Not even an incy one, I coax? `No.'

As a newspaper diary pointed out, there is something else in his history. While at Oxford, Ainsworth wanted to invite the National Front to speak at the Oxford Union and was allegedly angry when he wasn't allowed to do it. He looks deeply embarrassed. 'It was all about being irre- sponsible and young and wanting to poke the Lefties in the eyeball. It was foolish.' But was he a fellow traveller? He denies it vehemently.

I ask the shadow culture minister to show me an example of his poetry. He is coy. 'No, really, no.' I insist and finally, with a wary expression, he pulls out a sheet from a drawer. 'This is something I wrote after the Labour conference. It's not very good.'

Peter's not talking to Gordon Who gave him a nasty look, And David's not talking to Tony— And nobody's talking to Cook And Jack doesn't think much of Cherie And Clare thinks Jack should go, And John won't talk to Robin It's forbidden to talk to Mo But Gordon is talking to no one He thinks that Tony's too wet He's biding his time. But they have no time Because we'll kick them out.

No sweat.

Previous page

Previous page