Exhibitions 1

In Celebration: The Art of the Country House (Tate Gallery, till 28 February)

Ancestor worship

Martin Gayford There are occasions when the branding contrives to raise all the wrong, awkward questions. Thus a campaign for the Inde- pendent, a while back, insisting that it still was, more or less dared you mentally to reply, 'Oh no, it isn't.' Similarly, in a small way, In Celebration: The Art of the Country House (sponsored by Aon Risk Services Ltd, in association with ITT London & Edinburgh) managed to make me contrary almost before I'd got through the door.

It is, however, an unassuming exhibition, marking the 25th anniversary of the His- toric Houses Association, and contains a number of exhibits which are well worth examination (to which I'll come a little later). But, right at the start, I found myself asking, 'The art of the country house? Exactly what is that, pray?' There's been a good deal of art in country houses over the years — although at this stage, much of the best has been sold off. But the art indige- nous to country houses, created solely for their embellishment, consists almost entire- ly of pictures of the owners, their livestock and their property.

Of course, there were great collections formed, but these were very much the exception, and existed only for a limited period. Few of the landed aristocracy were interested in purchasing anything but por- traits until the 18th century; by the 1830s, as Robert Upstone notes in the catalogue, they had been overtaken as collectors for good — by the nouveaux riches of finance and industry.

The late Osbert Lancaster once conjec- tured that archaeologists of the future, examining the remains of the style of deco- ration he dubbed 'Scottish Baronial' — fea- turing forests of antlers and hecatombs of decapitated game — would conclude that the religion of the inhabitants had been some form of totemism. Similarly, entering the average country house one might well imagine that the proprietors had practised ancestor worship.

Although, of course, Anglicanism was the official creed, that guess would not be so wide of the mark. Already in the early 17th century, on inspecting the huge gallery of largely fictional forebears accumulated by Lord Lumley, James I was moved to remark, 'I didna ken that Adam's other name was Lumley' (a surprisingly witty remark for a king).

Subsequently, the philistine insistence of the aristocracy on buying nothing but por- traits, of people, animals or estates, did much to stunt and skew the development of art in England. It was — with the added, later, fashion for buying other varieties of painting if and only if they were old and foreign — the subject of much bitter denunciation by artists such as Hogarth. All of this is interesting, but a cause for cel- ebration ... well, I rest my case.

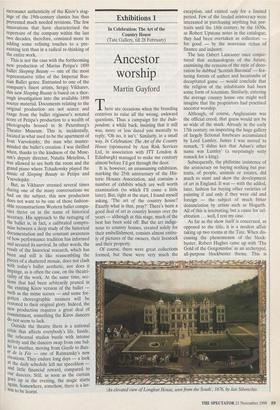

As far as the show itself is concerned, as opposed to the title, it is a modest affair taking up two rooms at the Tate. When dis- cussing the phenomenon of the block- buster, Robert Hughes came up with 'The Gold of the Gorgonzolas' as an archetypal, all-purpose blockbuster theme. This is An elevated view of Longleat House, seen from the South, 1676, by Jan Siberechts more on the lines of 'The Lumber-rooms of Littlehampton' — and all the more engaging for that. Indeed, Osbert Lancast- er — the most acute observer of this coun- try house terrain — keeps coming to mind.

There are naturally a lot of portraits, some of them marvellous. A grand van Dyck depicts Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, and Alatheia, Countess of Arun- del, presiding over a massive globe, which occupies the subservient position in the composition more often taken by a faithful retainer or mastiff. The Countess holds a pair of dividers with a distinctly glum expression, her hairstyle suggesting that the frizzy perm was not unknown to the age of Charles I. The Earl points at Madagascar, the object of a fruitless attempt at colonisa- tion on his part.

A beautiful Zoffany portrays the nobly pear-shaped form of George, 3rd Earl Cow- per — one of the artistically minded gentry, who fled the 'dull melancholy of England' to live in Florence, where he is prominently to be seen inspecting the works in Zoffany's `Tribune of the Uffizi'. An equally beautiful Lucian Freud from Chatsworth, 'Head of a Woman', 1950, is the most distinguished result of 20th-century country house patronage (an interest in living art, as shown by the Devonshires and the Sitwells, is just as rare a trait in the shires as it is among the rest of the population).

My favourite, or at least the most obvi- ous candidate for Lancaster's Littlehamp- ton Bequest, is the Elizabethan portrait of Peregrine, 12th Baron Willoughby de Eres- by, who has declined into an allegorical melancholy as a result of expenses incurred in the wars in the Low Countries. An accompanying board announces that schol- arly research has established he was indeed the 12th Baron, and not the 13th, as previ- ously thought.

There is also on show a fine Stubbs, of Gimcrack on a bleak Newmarket Heath, a Leonardo drawing, a Turner watercolour, a Claude, and a Holbein drawing — of Sir George Nevill, 3rd Baron Abergavenny which somehow got separated from his other studies of the Tudor court, now at Windsor. From a historical point of view the most unusual, perhaps, is the painting of a crowd of weightless Elizabethan gen- tlemen carrying the Queen in a litter whose canopy is embroidered with a floral, Laura Ashleyish design. It dates from c. 1601, when Elizabeth was approaching 70, and diplomatically represents her as a woman — or possibly cardboard cut-out — of around 25.

There is also a good deal of country house bric-A-brac of the sort you do not often see at the Tate (except in the con- temporary galleries). On display, for exam- ple, is a death mask of Napoleon from Bowood, a mediaeval Irish drinking cup, an 18th-century coronet belonging to the Earl of Northumberland, and an early album of photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron recently discovered at Eastnor Castle in a turret room, abandoned because the roof had collapsed.

Now that aspect of country houses — as cobwebby middens, crammed with the accumulated bibs and bobs of ages — real- ly is irresistible. In Celebration: The Attics of the Country House — there's the title the Tate should have gone for, though it's probably too late to change it.

Previous page

Previous page