Old and young man Rivera

Bevis Hillier

DREAMING WITH HIS EYES OPEN by Patrick Marnham Bloomsbury, £20, pp. 370 There are three unanswerable ques- tions for my generation (b.1940). We are a fortunate generation — at least in Britain — in that we have never been conscripted to fight in a war, and will be too old to fight in the next one. But that leaves me with the question: how would I have behaved under fire? We are an unfortunate generation in that we have spent our lives in the shadow of the dunghill of contemporary art. I think the rot began with Picasso, a gimmicky pattern-maker who just about found his right level in the robust pottery designs now on show at the Royal Academy. But that leaves me with the awkward question, `How would I, if alive in the 1870s, have responded to, the Impressionists? Would I have dismissed them as inept or as charla- tans because they were not trying to be Leonardo, Retnbrandt or Vermeer?' I trust not, but I cannot be sure. Iry final ques- tion: if I had been a young man in the early 1900s, instead of the 1960s, what would have been my attitude to the suffragettes? I do not believe I would have taken the `anti' line that Winston Churchill took.

I absolutely understand the feminism that demanded suffrage. Women have to obey the laws, therefore they should have a say in enacting them. But there is a type of feminism I have never comprehended. It is the sort which decreed that a Museum of Women's Art should be set up in Washing- ton DC in the 1980s. That lack of a penis should qualify an artist for special honour is a curious proposition — I mean, why not a museum for the art of bald-headed men? If women artists were required to enter such an aesthetic ghetto — rather as women undergraduates at Oxbridge once had to live in clinic-like, modern, single-sex colleges rather than the beautiful mediae- val co-ed colleges they now adorn — they would protest, and justifiably. It might make sense if women's art were somehow generically different from men's; but it is not. Germaine Greer's splendidly researched book on women artists, The Obstacle Race (1979), does not illustrate a single work of which one would exclaim, 'By God, that must be by a woman!' Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt were fine artists, but they do not match up to Boudin and Degas respectively. Even Artemisia Gen- tileschi, the 17th-century artist to whom Greer devotes a chapter headed 'The Mag- nificent Exception', did no more than turn out able pastiches of Caravaggio, a friend of her father's. There are good artists, bad artists and indifferent artists. That women artists should be lumped together for special treatment is part of the Wimmin's Studies' fad that has distorted academe in America and to some extent in Britain.

One victim of this tendency has been the Mexican mural artist Diego Rivera (1886- 1957). In 1929 Rivera married Frida Kahlo, an artist touched with surrealism and more than touched with craziness. The Wimmin's Studies gang have seized on Kahlo at the expense of Rivera. This process had already begun when Germaine Greer wrote her book. Of Kahlo, she asserted:

In her painting, which remained steadfastly independent of her husband's style, strongly rooted in peasant and votive art, she worked out the drama of her love for a man who was incapable of any such feeling, a love which remained generous and constant through all her physical pain, her despairing miscarriages and Rivera's infidelities, a divorce and remarriage.

Constant! Frida Kahlo was about as con- stant as President Clinton — and even his dalliances have not extended, so far as we know, to both sexes, as did hers. The only sense in which 'constant' could be applied to her was as it was applied to the young lady in the verse:

There was a young lady of Spain Who liked it now and again;

Not now and again, but now -

And again and again and again.

Greer had another good go at rubbishing Rivera in her caption to Kahlo's double- portrait `Frida and Diego' :

Frida Kahlo's stylistic independence is obvious in this ironic version of a folk bridal portrait. Her small hand, placed over Rivera's rather than in it, moors him like a baby-shaped balloon to her figure.

Patrick Marnham's book is a straight biography, not a coffee-table art book. In a preface, he complains of the two difficul- ties that beset any modern biographer of Rivera. The first is the 'tapestry of myths' that he wove round his own life; he was 'a master of disguise':

To complicate this fundamental problem [Marnham writes] there is now an additional distortion, the myth that has been made out of the life of Frida Kahlo. As this has grown up, Rivera has been transformed into a two-dimensional monster, although many people who knew them both well reject this view.

The idea that Frida Kahlo was a better person, even a better artist, than Rivera, is only one of the distortions Marnham tries to redress. The line I have always been sold on Rivera is that he was an idealistic Marx- ist who chose to paint murals because through them he could send messages to illiterate Mexican peasants. That is precise- ly the view of Rivera which Anthony Blunt, writing at the age of 24 and already woolly with Marxism, suggested: The ultimate object of the paintings is always propaganda . . . to expound the lesson of Communism, just as that of the mediaeval artist was to expound the lesson of Christian- ity . . If mediaeval art was the Bible of the illiterife, Rivera's frescoes are the Kapital of the illiterate.

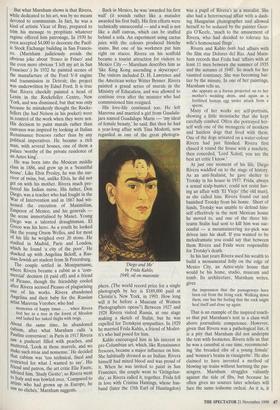

'Dream of a Sunday afternoon in the Alameda, 1948, fresco (Hotel del Prado, Mexico City) But what Marnham shows is that Rivera, while dedicated to his art, was by no means devoted to communism. In fact, he was a kind of artistic Vicar of Bray, prepared to trim his message to propitiate whatever regime offered him patronage. In 1930 he even accepted $4,000 to decorate the Pacif- ic Stock Exchange building in San Francis- co. (Marnham judiciously avoids the obvious joke about 'fresco in Frisco' and the even more obvious 'I left my art in San Francisco'.) In 1932 he painted scenes of the manufacture of the Ford V-8 engine and transmission in Detroit; the project was underwritten by Edsel Ford. It is true that Rivera cheekily painted a head of Lenin in the Rockefeller Centre, New York, and was dismissed; but that was only because he mistakenly thought the Rocke- fellers (he had Nelson in his pocket) were in control of the work when they were not. His decision to paint murals rather than canvases was inspired by looking at Italian Renaissance frescoes rather than by any political imperatives. He became a rich man, with several houses, one of them a palace 'worthy of the private residence of an Aztec king'.

He was born into the Mexican middle class in 1886, and grew up in a 'beautiful house'. Like Elvis Presley, he was the sur- vivor of twins, but, unlike Elvis, he did not get on with his mother. Rivera much pre- ferred his Indian nurse. His father, Don Diego, was a teacher who had fought in the War of Intervention and in 1867 had wit- nessed the execution of Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico, and his generals the scene immortalised by Manet. Young Diego was a talented draughtsman. El Greco was his hero. As a youth he looked like the young Orson Welles, and for most of his life he weighed over 20 stone. He studied in Madrid, Paris and London, which he found 'a city of the poor'. He shacked up with Angelina Beloff, a Rus- sian-Jewish art student from St Petersburg.

The couple settled in Montparnasse, where Rivera became a cubist as a 'com- mercial' decision (it paid off) and a friend of Picasso, though the friendship cooled after Rivera accused Picasso of plagiarising one of his works. Rivera abandoned Angelina and their baby for the Russian artist Marevna Vorobev, who had

memories of happy times . . . when Rivera tied her to a tree in the forest of Meudon and lashed her naked thighs with twigs.

About the same time, he abandoned cubism, after what Marnham calls 'a Pauline conversion': in Paris in 1917 Rivera saw a pushcart filled with peaches, and muttered, 'Look at those marvels, and we make such trivia and nonsense.' He decided that cubism was 'too technical, fixed and restricted for what I wanted to say'. His friend and patron, the art critic Elie Faure, advised him, 'Study Giotto'; so Rivera went to Italy and was bowled over. 'Compared to artists who had grown up in Europe, he saw no clichés,' Marnham suggests. Back in Mexico, he was 'awarded his first wall' (it sounds rather like a matador awarded his first bull). His first efforts were technically unsuccessful — and a wall is not like a duff canvas, which can be stuffed behind a sofa. An experiment using cactus juice with the colours produced blotchy stains. But one of his workmen put him right on stucco. Rivera on his scaffold became a tourist attraction for visitors to Mexico City — Mamham describes him as `like King Kong ascending a skyscraper'. The visitors included D. H. Lawrence and the American writer Witter Bynner. Rivera painted a grand series of murals in the Ministry of Education, and was allowed to continue even after the minister who had commissioned him resigned.

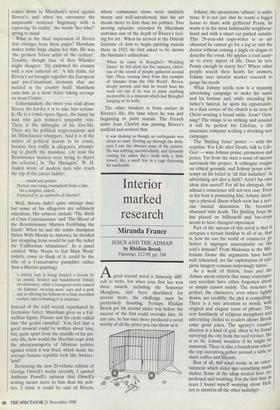

His love-life continued too. He left Marevna and married a girl from Guadala- jara named Guadalupe Marin — 'my ideal of female beauty,' he said. But then he had a year-long affair with Tina Modotti, now regarded as one of the great photogra- Diego and Me' by Frida Kahlo, 1949, oil on masonite phers. (The world record price for a single photograph by her is $189,000 paid at Christie's, New York, in 1993. How long will it be before a Museum of Women Photographers opens?) Between 1927 and 1928 Rivera visited Russia, at one stage making a. sketch of Stalin; but he was expelled for Trotskyist sympathies. In 1929 he married Frida Kahlo, a friend of Modot- ti's who had posed for him.

Kahlo encouraged him in his interest in pre-Columbian art, which, like Renaissance frescoes, became a major influence on him. She habitually dressed as an Indian. Rivera himself had mixed blood and was proud of it. When he was invited to paint in San Francisco, the couple went to 'Gringolan- dia', as Rivera called it, together. Frida fell in love with Cristina Hastings, whose hus- band (later the 15th Earl of Huntingdon) was a pupil of Rivera's as a muralist. She also had a heterosexual affair with a dash- ing Hungarian photographer and allowed herself to be seduced by the painter Geor- gia O'Keefe, 'much to the amusement of Rivera, who had decided to tolerate his wife's homosexual flings'.

Rivera and Kahlo both had affairs with the film star Dolores del Rio. And Marn- ham records that Frida had 'affairs with at least 11 men between the summer of 1935 and the autumn of 1940'. So much for her vaunted constancy. She was becoming bat- tier by the minute. In one of her paintings, Marnham tells us,

she appears as a foetus projected on to her mother's wedding dress, and again as a fertilised human egg under attack from a sperm.

Many of her works are self-portraits, showing a little moustache that she kept carefully combed. Often she portrayed her- self with one of the menagerie of monkeys and hairless dogs that lived with them. One of the dogs urinated on a water-colour Rivera had just finished. Rivera first chased it round the house with a machete, then conceded, 'Lord Xolotl, you are the best art critic I know.'

At just one moment of his life, Diego Rivera waddled on to the stage of history. As an anti-Stalinist, he gave shelter to Trotsky in his house in 1937. Frida, always a sexual scalp-hunter, could not resist hav- ing an affair with 'El Viejo' (the old man), as she called him. Rivera found out and banished Trotsky from his home. Short of funds, Trotsky was unable to defend him- self effectively in the next Mexican house he moved to, and one of the three hit- teams Stalin had sent to kill him was suc- cessful — a mountaineering ice-pick was driven into his skull. If you wanted to be melodramatic you could say that between them Rivera and Frida were responsible for Trotsky's death.

In his last years Rivera used his wealth to build a monumental folly on the edge of Mexico City, an Aztec-style house that would be his home, studio, museum and tomb. Its architecture, Mamham writes, gives

the impression that the passageways have been cut from the living rock. Walking down them, one has the feeling that the rock might heal itself and close up again.

That is an example of the inspired touch- es that put Marnham's text in a class well above journalistic competence. However, given that Rivera was a pathological liar, it is a pity that Marnham did not underpin the text with footnotes. Rivera tells us that he was a cannibal at one time, recommend- ing 'the breaded ribs of a young female' and `women's brains in vinaigrette'. He also claimed to have invented a method of blowing up trains without harming the pas- sengers. Marnham struggles valiantly against the tide of fibs, but because he often gives no sources later scholars will face the same toilsome ordeal. As it is, it comes down to Marnham's word against Rivera's; and when we encounter the umpteenth sentence beginning with a reproving 'In reality', the words `Sez who?' spring to mind.

What is the final impression of Rivera that emerges from these pages? Marnham makes some large claims for him. He was `the greatest fresco artist of the century'. Tenable, though fans of Rex Whistler might disagree. `fle endowed his country with a new national art.' A fair claim, for Rivera's art brought together the European and pre-Columbian elements that are melded in the country itself. Marnham casts him as a stout Aztec taking revenge on stout Cortez.

Unfortunately, the more you read about Rivera the harder it is to take him serious- ly. He is a comic-opera figure, the funny fat man who gets women's sympathy vote. There is the imbroglio of his love-life. There are his political tergiversations and his Munchausen whoppers. And it is of the nature of political murals to be comic, because they traffic in allegories, attempt- ing to glorify the mundane. (At least the Renaissance masters were trying to depict the celestial.) In 'The Managers', W. H. Auden wrote of modern men who reach the top of the career ladder: ... would any painter

Portray one rising triumphant from a lake On a dolphin, naked, Protected by an umbrella of cherubs?

Well, Rivera didn't quite attempt that; but some of his allegories are sublimely ridiculous. His subjects include 'The Birth of Class Consciousness' and 'The Blood of the Revolutionary Martyrs Fertilising the Earth'. When he met the tennis champion Helen Wills Moody in America, he decided her strapping form would be just the ticket for 'Californian Abundance'. In a panel entitled 'Who Wants to Eat Must Work' (which, come to think of it, could be the title of a Conservative pamphlet rather than a Marxist painting)

a society lady is being handed a broom by an armed, booted and bandoliered female revolutionary, while a bourgeois artist named `de Sodoma' wearing asses' ears and a pink suit is offering his bottom to a blue-overalled worker, who is booting it in response.

Instead of the cold wretch reprobated by Germaine Greer, Marnham gives us a Fal- staffian figure. Picasso and his circle called him 'the genial cannibal'. You feel that a good musical could be written about him; but, quite apart from the muddle of his pri- vate life, how would the librettist cope with the phantasmagoria of Mexican politics against which it was lived, which made the average banana republic look like Switzer- land?

Reviewing the new 20-volume edition of George Orwell's works recently, I quoted Anthony Powell's opinion that Orwell's writing meant more to him than his poli- tics. I think it could be said of Rivera, whose communist views were similarly muzzy and well-intentioned, that his art meant more to him than his politics. Two moving episodes recorded by Marnham convince one of the depth of Rivera's feel- ing for art. When he arrived at the Detroit Institute of Arts to begin painting murals there in 1932, he first asked to be shown the Institute's collections.

When he came to Brueghel's 'Wedding Dance' he fell silent for five minutes, oblivi- ous of the crowd of people gathered around him. Then, turning away from this example of 'plunder from the Old World', Rivera, deeply moved, said that he would have his work cut out if he was to paint anything memorable in a museum which had Brueghel hanging on its walls.

The other incident is from earlier in Rivera's life, the time when he was just beginning to paint murals. The French artist Jean Charlot was passing Rivera's scaffold and noticed that

it was shaking as though an earthquake was about to start. Peering up through the dark- ness I saw the obscure mass of the painter. He was sobbing uncontrollably, and furiously erasing his entire day's work with a little trowel, like a small boy in a rage flattening his sandcastle.

Previous page

Previous page