A SUITABLE CASE FOR TREATMENT

Christina Lamb interviews

the President of Brazil, as he awaits impeachment and a possible jail sentence

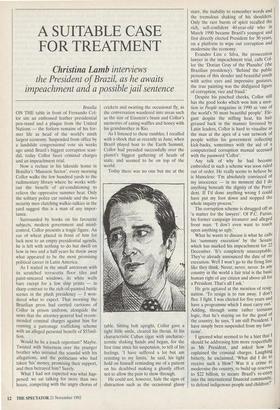

Brasilia ON THE table in front of Fernando Col- lor sits an embossed leather presidential pen-stand and a plaque from the United Nations — the forlorn remains of his for- mer life as head of the world's ninth largest economy. Suspended from office by a landslide congressional vote six weeks ago amid Brazil's biggest corruption scan- dal, today Collor faces criminal charges and an impeachment trial.

Now a recluse in his lakeside home in Brasilia's 'Mansion Sector', every morning Collor walks the few hundred yards to the rudimentary library where he works with- out the benefit of air-conditioning to relieve the oppressive summer heat. Only the solitary police car outside and the two security men clutching walkie-talkies in the yard suggest this is a man of any impor- tance.

Surrounded by books on his favourite subjects, modern government and mind- control, Collor presents a tragic figure. An ear of wheat placed in front of him for luck next to an empty presidential agenda, he is left with nothing to do but dwell on how in two and a half years he threw away what appeared to be the most promising political career in Latin America.

As I waited in the small anteroom with its scratched terracotta floor tiles and paint-smeared windows, its white walls bare except for a few ship prints — in sharp contrast to the rich oil-painted battle scenes in the plush presidency — I won- dered what to expect. That morning the Brazilian press had carried cartoons of Collor in prison uniform, alongside the news that the attorney-general had recom- mended criminal charges against him for running a patronage trafficking scheme with an alleged personal benefit of $55mil- lion.

Would he be a touch repentant? Maybe. Twisted with bitterness over the younger brother who initiated the scandal with his allegations, and the politicians who had taken 'his' money, promising their support, and then betrayed him? Surely.

What I had not expected was what hap- pened: we sat talking for more than two hours, competing with the angry chorus of crickets and swatting the occasional fly, as the conversation wandered into areas such as the size of Einstein's brain and Collor's memories of eating waffles and honey with his grandmother in Rio.

As I listened to these rambles, I recalled with a shock that as recently as June, when Brazil played host to the Earth Summit, Collor had presided successfully over the planet's biggest gathering of heads of state, and seemed to be on top of the world.

Today there was no one but me at the table. Sitting bolt upright, Collor gave a tight little smile, cleared his throat, lit his characteristic Cuban cigar with uncharac- teristic shaking hands and began, for the first time since his suspension, to tell of his feelings. 'I have suffered a lot but am resisting to my limits,' he said, his tight hold on himself reminding me of a patient on his deathbed making a ghastly effort not to allow the pain to show through.

He could not, however, hide the signs of distraction such as the occasional glassy stare, the inability to remember words and the tremulous shaking of his shoulders. Only the rare bursts of spirit recalled the rich, self-confident 40-year-old who in March 1990 became Brazil's youngest and first directly elected President for 30 years, on a platform to wipe out corruption and modernise the economy.

Evandro Lins e Silva, the prosecution lawyer in the impeachment trial, calls Col- lor the 'Dorian Gray of the Planalto' (the Brazilian presidency). 'Behind the public persona of this slender and beautiful youth with active eyes and impressive gestures, the true painting was the disfigured figure of corruption, vice and fraud.'

Despite his pinched cheeks, Collor still has the good looks which won him a men- tion in People magazine in 1990 as 'one of the world's 50 most beautiful people'. Ele- gant despite the stifling heat, his hair greased back in the manner favoured by Latin leaders, Collor is hard to visualise as the man at the apex of a vast network of people within his government collecting kick-backs, sometimes with the aid of a computerised corruption manual accessed with the password 'Collor'.

Any talk of why he had become embroiled in such a scheme was soon ruled out of order. He really seems to believe he is blameless: 'I'm absolutely convinced of my innocence — in no moment did I do anything beneath the dignity of the Presi- dent. If I'd done anything wrong I could have put my foot down and stopped the whole inquiry process.'

The corruption scheme is shrugged off as `a matter for the lawyers'. Of P.C. Farias, his former campaign treasurer and alleged front man: 'I don't even want to touch upon anything so ugly.' What he wants to discuss is what he calls his 'summary execution' by the Senate which has marked his impeachment for 22 December. 'It's completely unacceptable. They've already announced the date of my execution. Well I won't go to the firing line like they think. Never, never, never. In any country in the world a fair trial is the basic human right of any citizen and above all for a President. That's all I ask.'

He gets agitated at the mention of resig- nation. 'To resign is to run away. I don't flee. I fight. I was elected for five years and have a programme which I must carry out. Adding, through some rather tortuous logic, that he's staying on for the good of the country, he says, 'I am still President. I have simply been suspended from my func- tions'.

I ignored what seemed to be a hint that I should be addressing him more respectfully as Mr President, and asked how he explained the criminal charges. Laughing bitterly, he exclaimed, 'What did I do to receive such a blow? Was it a crime to modernise the country, to build up reserves to $22 billion, to secure Brazil's re-entry into the international financial community; to defend indigenous people and children? The way Collor tells it, he did nothing wrong and the whole 'lamentable episode', (as he calls it) was a campaign against him by vested interests angered by his moderni- sation programme to combat cartels and open Brazil's long protected economy to foreign competition. 'I was brought down by a combination of business and union elites that had their corporate interests harmed by my actions, and politicians who wanted power all under a false cloak of morality. These people don't care about clean administration.'

Apparently unaware of the irony, he con- tinued, 'I always saw power as an instru- ment for great social transformation, whereas they saw it as a way to great per- sonal satisfaction.'

Collor seems to believe that this 'great social transformation' is now threatened by his successor, whom he refuses to mention by name, referring to him only as 'the vice- president'. The vice-president is dragging Brazil into the fifth world,' Collor exclaimed.

Then, like a magician, he pulls out of his briefcase sheaves of documents showing measures passed by his government, decrees overturned and measures in progress, as well as a calendar marked with what is expected to be done when. 'Look at this,' he crows, picking one at random which turns out to be a rather insignificant measure about trade in tropical plants. I began, perhaps rather late in the day, to wonder what a psychiatrist would make of Fernando Collor.

He refuses to admit the strength of the nationwide street campaign against him demanding his impeachment. 'If a presi- dent had to resign every time a few people came out in the streets, then Helmut Kohl and John Major would both be out of office.'

Suspended from office himself, Collor's main interest now is in mind-control, a the- ory he expounds on at length: 'We are all born with the same hardware. Einstein's brain was no bigger than the next man's. The difference is in how we programme it. For this I am avoiding ignoble thoughts like hate and resentment as these are like a virus in the system.' Armed with his Einstein-sized brain, Col- lor clings to what straws he can find. Proudly he talks of letters of support from Fidel Castro and Jacques Cousteau. Some- one, he said, had told him that President Mitterrand was sympathetic. But somewhere in that half-crazed mind Fernando Collor must know there is little chance that he can avoid impeachment and eight years suspension from public office; even if given Brazil's tradition of impunity, he is unlikely to go to jail. He concluded our interview: 'The world has not seen the end of Fernando Collor.' He may be right. Brazilians have very short memories.

Christina Lamb is the Financial Times' cor- respondent in Brazil.

Previous page

Previous page