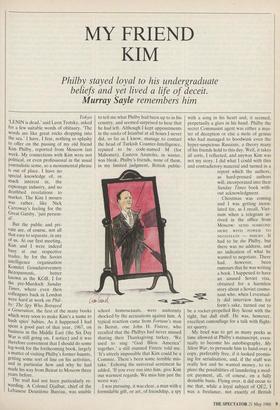

MY FRIEND KIM

Philby stayed loyal to his undergraduate beliefs and yet lived a life of deceit.

Murray Sayle remembers him Tokyo 'LENIN is dead,' said Leon Trotsky, asked for a few suitable words of obituary. 'The words are like great rocks dropping into the sea.' I have, I fear, nothing so splashy to offer on the passing of my old friend Kim Philby, reported from Moscow last week. My connections with Kim were not political, or even professional in the usual journalistic sense, so a monumental phrase Is out of place. I have no special knowledge of, or much interest in, the espionage industry, and no deathbed revelations to market. The Kim I mourn was rather, like Nick Carroway's feeling for the Great Gatsby, 'just person- al'.

But the public and pri- vate are, of course, not all that easy to separate, in any of us. At our first meeting, Kim and I were indeed busy at our respective trades, he for the Soviet intelligence organisation Komitet Gosudarstvennoy

Bezopasnosti, better known as the KGB, I for the pre-Murdoch Sunday Times, where even then colleagues back in London were hard at work on Phil- by: The Spy Who Betrayed a Generation, the first of the many books which were soon to make Kim's a name to hush spies' babies. As it happened I had spent a good part of that year, 1967, on business in the Middle East (the Six Day War is still going on, I notice) and it was therefore convenient that I should do some leg-work for the forthcoming book, largely a matter of visiting Philby's former haunts, getting some sort of line on his activities, and in particular how and why he had made his way from Beirut to Moscow three years before.

The trail had not been particularly re- warding. A Colonel Djalbut, chief of the Lebanese Deuxieme Bureau, was unable

to tell me what Philby had been up to in his country, and seemed surprised to hear that he had left. Although I kept appointments in the souks of Istanbul at all hours I never did, so far as I know, manage to contact the head of Turkish Counter-Intelligence, reputed to be code-named M (for Mahomet). Eastern Anatolia, in winter, was bleak. Philby's friends, none of them, in my limited judgment, British public- school homosexuals, were uniformly shocked by the accusations against him. A typical reaction came from Fortune's man in Beirut, one John H. Fistere, who recalled that the Philbys had never missed sharing their Thanksgiving turkey. 'We used to sing "God Bless America" together,' a still stunned Fistere told me. 'It's utterly impossible that Kim could be a Commie. There's been some terrible mis- take.' Echoing the universal sentiment he added, 'If you ever run into him, give Kim our warmest regards. We miss him just the worst way.'

I was pursuing, it was clear, a man with a formidable gift, or art, of friendship, a spy with a song in his heart and, it seemed, perpetually a glass in his hand. Philby the secret Communist agent was either a mas- ter of deception or else a mole of genius who had managed to hoodwink even the hyper-suspicious Russians, a theory many of his friends hold to this day. Well, it takes all sorts, I reflected, and anyway Kim was not my story. I did what I could with thin and contradictory material and turned in a report which the authors, as hard-pressed authors will, incorporated into their Sunday Times book with- out acknowledgment.

Christmas was coming and I was getting inocu- lated for, as I recall, Viet- nam when a telegram ar- rived in the office from

MOSCOW: SEND SOMEONE HERE WITH POWER TO NEGOTIATE — PHILBY. It had to be the Philby, but there was no address, and no indication of what he wanted to negotiate. There had, however, been rumours that he was writing a book. I happened to have an unused Soviet visa, obtained for a harmless story about a Soviet cosmo- naut who, when I eventual- ly did interview him for form's sake, turned out to be a rocket-propelled Boy Scout with the right, but dull stuff. He was, however, excellent camouflage for a talk with flight- ier quarry.

My brief was to get as many peeks as time allowed at Philby's manuscript, even- tually to become his autobiography, My Silent War, to persuade him to hand over a copy, preferably free, if it looked promis- ing for serialisation, and, if the stuff was really hot and he wanted money, to ex- plore the possibilities of laundering a mod- est payment, all, of course, on a fully deniable basis. Flying over, it did occur to me that, while a loyal subject of QE2, I was a freelance, not exactly of British

nationality, and so, at a pinch, reasonably deniable myself.

So how to find Philby, with discretion? Hanging about the back door of the KGB was not, perhaps, the approach of choice. Philby was, however, said to keep in touch with the Old Country, particularly the cricket scores. In those pre-facsimile days that had to mean the Times and regular visits to the less forbidding Foreign Post Office in Kirov Street. There I stationed myself, moved on occasionally by a bored militiaman but otherwise undisturbed, un- til, sure enough, a ruddy-faced, stocky man in the tweed jacket, wool shirt and flannel bags of the 1930s British intellectual walked in, rather jauntily.

'Mr Philby?'

He seemed to be expecting me. 'W-w- where are you staying?'

'The Leningradskaya.' I gave him a visiting card.

'I'll t-t-telephone you.' He was gone. My room at the Leningradskaya, a hotel in the Stalin wedding-cake style, was unin- spiring. I recall long stained drapes, one dim bulb in an enormous chandelier, a polished marble inkwell and pen with a bent, rusty nib. Eventually the telephone, a prop from Dr Zhivago, rang and Philby, after several tongue-tied attempts, gave me an appointment for that night, in Room 436 of the Minsk Hotel on Gorky Boule- vard.

The fourth floor of the Minsk had a long dim corridor where, at either end, large plug-ugly men in blue suits with bulging left armpits lounged non-nonchalantly. I knocked at 436. `C-come in,' said a cheer- ful voice. Inside by an uncurtained window was a table, bare except for two glasses and a bottle of vodka, a briefcase, two hard chairs and, on one of them, Kim. I sat on the other. Kim opened the briefcase and produced a scratchpad. Still inside were a bulky document and what looked like a pistol, or possibly a joke cigarette-lighter — a conversational piece, perhaps, to break the ice?

'I'll assume you c-c-come from the other side,' said Philby.

'I'm just an old-time travelling news- man, Kim,' I explained. 'You know, a green tennis eyeshade and a bag of plum- ber's tools to fix the presses. But I suppose I would say that, wouldn't I?'

Philby laughed. 'L-let's have a drink, anyway,' he said. The cork was already loosened, so perhaps that was a bottle- opener in his briefcase. We drank, the first of many, shuddered pleasantly, and got down to business.

There was indeed a manuscript, said Philby, but it was still a little early to show it. Yes, it was an account of his career as a spy. Naming names, dates and places? 'W-well, I am a s-serving officer of the KGB,' said Kim, as if I didn't know, 'and I say nothing about my work for the Soviet Union in my book, naturally. My history becomes rather general after about 1955. I have to think about protecting our own operations after that date.' However, he said, he was quite ready to be frank about his other career, as head of the anti-Soviet section of the British intelligence service, MI6, with as much detail as anyone could want. 'I n-n-name my old colleagues of the SIS, CIA and FBI,' he said, 'not in an unkindly way, I hope, just setting down the facts.'

Our first meeting was agreeable, but inconclusive. 'Let's m-m-meet for lunch,' Philby suggested, as we parted at the Minsk. 'Outside my office, t-tomorrow at 12.30.' There was a final altercation with the concierge, a stout lady comrade who rudely claimed back the hotel's glasses. Kim, I noted, spoke rudimentary Russian. It was late as I walked, or rather floated, home across deserted Red Square, medi- tating on the evening. Snow was drifting down on the cobblestones and Lenin's tomb, muffling the boots of the Red Air Force guard and staining the sky pink around the enormous red stars glowing on the Kremlin spires. It might not be, as Kim had asserted earlier in the evening, the 'vibrant dynamic city of the future', but Moscow is certainly not any old run-of-the- mill old-world capital, either.

The headquarters of the KGB are in an old insurance building in Dzerzinsky Square, named after the founder of the organisation. It has broad steps, flanked on either side by barred basement windows. At 12.30 sharp, fresh as a snowdrop, Kim came trotting out. `C-can you hear them s-s-screaming down there?' he asked cheer- fully. 'Yes, I hear them, Kim,' I said. 'Where are we going?' That day it was the Mount Ararat, an Armenian establishment where the waiters' jackets are embroidered with the double peak of the mountain, leading to a lot of jokes about which side we were looking at. (The possibility that Kim had escaped to the Soviet Union via Armenia was the topic I was hoping to pursue with M, the elusive Turkish spook.)

Now that it can no longer hurt his feelings, I should describe what I have so far merely indicated, the most immediately noticeable and memorable thing about Kim, his stammer. It was so severe that, on occasion, it would take him minutes to get a difficult sound out. These were not, however, the words like 'arrest', 'interro- gate' or 'jail' that he might have been expected to stumble over, but rather the hard consonants k, p, b and so on that bother all stammerers. But even with his handicap Kim was an engaging wit and raconteur, an original combination I have never encountered in anyone else.

Many politicians and others dependent on public esteem go in for lisps, stutters and bizarre pronunciations, come to think of it, and these afflictions may serve to make the sufferer more likeable. Adolf Hitler, for instance, would have got far praising the Third Weich. Kim had learnt to talk around his stammer and often used it for comic timing, and possibly to deflect difficult questions. According to My Silent War, he began stammering in 1916 when his parents first brought him from India, where he was born, to dump him on his grandmother. He can hardly have begun preparations for a career with the KGB at the age of four, so perhaps we have an indication here of some deeper conflict, a conclusion possibly reinforced by the re- mark of Spycatcher Peter Wright, late of MI5 that he, too, has stammered since childhood.

Wright once bugged Philby at a press conference but neither, it seems, ever interrogated the other, thus denying spy literature one of its more entertaining moments. These stammers may, of course, be mere coincidence; but again it may be that speech difficulties and a vocation for the profession that prefers not to speak its name have a common source in the traumas of childhood, the shades of the prisonhouse that, as Wordsworth says, have a tendency to close upon the growing boy, or spy. A sample of Philby the conversationalist and concerned spymaster illustrates the point.

While his manuscript did, said Kim after a reunion drink at the Ararat, let many c-cats out of the b-bag, he had another proposal to make. He was concerned about the fate of an American couple named Peter and Helen Kroger, once part of the Rosenberg nuclear spying operation in the United States, who later operated a ring of their own, spying on Royal Navy torpedo research at Portland in Dorset (an assign- ment rather flattering to the Silent Service, I thought at the time) and who were, even as Kim and I settled into the vodka, doing long stretches in depressing British prisons.

Philby's plan was that this rather pathe- tic pair should be exchanged for Gerald Brooke, an Englishman who had been arrested in Moscow, supposedly while handing out religious literature in Red Square, and then reported to be carving a work norm of 120 chessmen a day in a labour camp on the Arctic Circle. If this exchange came off, said Philby, then he would consider withdrawing his book, a sacrifice any author would sympathise with.

'I'm afraid I have no authority to close any deals like that, Kim,' I said, 'but I can see a problem straight away. There are two Krogers and only one Brooke.'

'It's always going to be 1-like that,' said Philby. 'We have m-more and b-better spies than you have. You know why? Ours. operate out of c-conviction, while yours w-work for m-money. That's how we catch them' — he rubbed a thumb and forefinger together — 'they have t-too much m- money.' In fact, I saw recently, the Walker spy family in the United States collected a grand total of $1,084,200 for, as the pat- riarch Johnny Walker put it, 'moving

product' on US Navy codes to Moscow. Volunteer spies with pro-Soviet convic- tions are thinner on the ground than they were in 1933, it seems.

At a later meeting with Kim in another restaurant, I reverted to the Krogers/ Brooke exchange (which eventually came off), with the idea of at least bringing the prospective merchandise closer to market.

`Surely, Kim, your side are not helping things along by ill-treating Brooke in a labour camp,' I said. 'Why not bring him down to Moscow until the deal goes through?'

`C-certainly not,' said Philby indignant- ly. 'Brooke is our p-prisoner, not yours, and we are treating him in accordance with S-Soviet law. Then again he's in p-p- prison. You're not in p-prison to get all th-th-this' (including with a wave our table loaded with vodka, caviar, brandy and assorted Soviet wines). '13-p-prisons are supposed to be unp-p-pleasant. That's why I t-t-took such g-g-g-g-g-g. . .' He stalled. I leaned forward, longing to help him finish whatever he was trying to say, totally disarmed. . . 'g-good care to stay out of them! W-what will you have?'

After lunch came dinner, and then more lunches and more dinners, all eaten out. I never saw his flat, which was, I believe, conveniently around the corner from the Minsk, his local as it were. John Philby, Kim's eldest son, who has kept us in touch over the years, arrived in Moscow to see his father during my visit and accompanied us several times on what he called 'getting pissed in pectopahs' (PECTOPAH being the Cyrillic form of RESTORAN) but which were, for me, mid-20th-century his- tory from a novel angle, and for Kim the chance to present his apologia pro vita sua — not that he admitted for a second that he had done anything that needed any apolo- gia. 'I was never a traitor,' he told me. 'To betray you must first belong, and I never belonged. I have followed exactly the same line all my adult life. I was a straight Soviet penetration agent. If your side were silly enough to let me get away with it, that's your look-out.' The logic of this is of course impeccable, but the penetrated parties understandably feel let down, and Kim's real motives, I suspected, lay deep- er.

His career began, Kim told me, when Ramsay MacDonald betrayed the working class, and therefore suffering humanity, with his National Government of August 1931. In nappies myself at the time, Down Under nappies at that, I was still able with hindsight to agree that capitalism was not then looking its best, and that the new British government's plan to deal with the crisis by cutting the dole, balancing the budget and lowering wages was essentially unsound. Two years later Kim, down from Cambridge and just 21, went to Europe to see what was happening there, and was present when the clerical-fascist Dollfuss regime shelled the workers' flats in Vien- na. Along with Hugh Gaitskell, Stephen Spender, Naomi Mitchison and the other young British intellectuals who witnessed the event, Kim was horrified, and his new Communist girlfriend, Litzi Friedman, was able to argue persuasively that Commun- ists were offering the only effective resist- ance to fascism, and that the time for action was at hand.

The young always think that, and back in England Kim was recruited, not by the Communist Party, but by the Soviet intelli- gence network as a sort of junior prob- ationer. Nothing unusual there; about the same time, for instance, Arthur Koestler became a secret member of the German Communist Party and its intelligence orga- nisation. As Kim recalled these formative years, over many refills of vodka, I cast the odd ideological fly: the Second Thesis on Feuerbach, the Gotha programme, Lenin's Emperio-Criticism. No bites. Not only was he no Russian scholar, he was not even a Marxist, in anything much more than a tribal sense, which must have greatly eased the task of concealing his true allegiance. The more I saw of Kim, indeed, the less he looked like New Soviet Man and the more he came over as a stubborn, old-fashioned English eccentric, sticking to rusty guns and be damned to the lot of you — rather like his own Muslim-convert, Arabia- exploring father, St John Philby, in fact.

As to Communism vs Fascism, or Stalin vs Hitler, Kim in 1933 certainly made the same choice the whole democratic or bourgeois world, rather baulkily it is true, made only a few years later. I allowed this point, and Kim called for another 300 grams of vodka. Our talks took place, in fact, over considerable quantities of booze, consumed, however, at a gentlemanly pace, Lord Thomson of Fleet and the KGB manfully standing round for round. Kim's drinking was remote from the alco- holic's downing of anything with a kick as fast as possible, nor did I detect any change in his personality as the nights wore on (or perhaps mine changed in sympathy). I saw him wince silently more than once in crowded pectopahs as Soviet officers in uniform vomited under nearby tables. Kim was not, I should judge, a compulsive, wardrobe or filing cabinet drinker, but rather a man with a strong head who relished the instant gaiety and friendship that come, so handily packed, in litre and half-litre bottles.

Well, I don't mind a drop myself now and again and I certainly enjoyed sinking a few, or more than a few, with Kim. Neither of us could by then have expected much of the other, but we had, it seemed, a lot in common. I have no periaiihl vocation for spying, but we had both, we found, seen interesting things in out-of-the-way places, and so were on the same side of the gulf forever set between those who go and those who stay at home. Then again, spying on General Franco for the KGB could be seen as balancing reporting for the Times, Kim's other job in Spain, and the Soviets were rather more than useful auxiliaries in the war against Hitler. As to the atom- bomb, if Kim had a hand in that (as his concern for the Krogers suggested) then there certainly was a case for the Soviets getting it, as a respectable body of scientific opinion urged at the time. They were going to build one anyway, and a balance of terror, which Kim may have helped along, still seems the best anyone can expect from this regrettable invention.

All this is arguable, but what I found engaging about Kim was not his politics but his personal attitudes. He was a little immodest, perhaps, but in a modest way, and from a professional point of view he had quite enough to be modest about. D-don't believe in g-gongs much my- myself,' he said one night, showing me his enamelled Order of the Red Banner in its demure case. But he never wore it, despite its magical effect on Soviet waiters, and we stood in line just like any other Muscovites to get into a popular pectopah.

About his non-political friends, and peo- ple you would not expect to be his friends, his feelings were unfailingly warm. He said he was very fond, for instance, of the writer Peter Kemp, whom he knew in Spain when Kemp was fighting without equivocation for Franco. About Allen Dulles, head of the CIA when Philby was in Washington, he recalled, 'A very d- decent old stick, Allen. Not p-perhaps overbright, but a hard w-worker [great praise from Philby] and a thorough g- gentleman.' He found J. Edgar Hoover, however, 'a thoroughly n-nasty p-piece of work', an opinion shared by almost every- one who met the FBI chief.

It was easy to divine where Philby found his endearing generosity of judgment. The presiding genius of Cambridge when he was there was not so much Karl Marx as the philosopher G. E. Moore, author of the Principia Ethica, who held that friendship and beauty were the best things in life. 'If I had to choose between bet- raying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country,' famously wrote Moore's disciple, E. M. Forster, a writer Philby's raffish Cambridge friend Guy Burgess years later tried to get published in Moscow, without success. The connection between Moore and the Cambridge school of Soviet agents has intrigued and annoyed more than one student of the phenomenon — ' "Only connect", Forster told them,' complained the novelist John Le Carre, `and they connected with the KGB' — but it is, I think, easy enough to understand.

It was 1933, a year when the proletariat was visibly getting the dirty end of the economic stick. The Cambridge group were in late adolescence, the age when youngsters are notoriously liable to join yuppies, hippies, Moonies, Tories or what- ever, or some simple shining path to a better world. That from Cambridge myste- rious Moscow looked like the city on the hill is less surprising, perhaps, than that a later generation saw the same vision in faraway Hanoi, Havana or even P'yong- yang. An enlarged patriotism, friendship for the whole human race, could well have looked to these uncomfortably privileged young people like Moore updated for the hungry 1930s.

That explains why Kim became a Com- munist, but not why he became an unpaid Soviet penetration agent, an unusual career choice at 22. Most of his contempor- aries, even the committed Cambridge Communists, preferred to start more mod- estly, with the boring meeting, perhaps, or the flat ephemeral pamphlet. The same question applies even more forcefully to Burgess: flamboyant homosexual, spec- tacular drunk, given to boasting in his cups that he was a Russian agent, the ultimate security risk and surely the most inept spy ever to stagger out of a safe house. What conceivable use could he have been in the underground? Yet when Kim was ens- conced in Washington under excellent cov- er, browsing, for Moscow, through the files of the CIA and the FBI, he took Burgess in as a house guest, and John Philby recalls as a baby playing among the mounds of bottles the pair emptied at the weekends. The flight of Burgess and Maclean to the Soviet Union effectively and predictably ended Kim's career. Why keep such con- spicuously, utterly unprofessional com- pany?

'Guy was my friend,' Kim told me in Moscow. 'It was an unw-wise f-friendship.' So, at the critical moment Kim had run true, not to Moscow but to Cambridge form. Faced by Forster's Fork, rather than be inhospitable to his friend he had, inadvertently or perhaps not, betrayed the workers' paradise he had never seen, exactly as old G. E. Moore recommended. But why, then, did Kim not decamp to a boozy retirement in Moscow with Burgess and his friend, Donald Maclean? Why did he soldier on for a dreary decade, metaphorically out in the cold in Beirut, scraping a precarious living as a freelance journalist, nose pressed wistfully against the glass of the secret world he could never really re-enter?

I puzzled over this as I drank with Kim. I have considered it many times since, and I wonder about it now. What was his secret spring? In My Silent War he writes, unex- pectedly, of 'the strain of irresponsibility which I think essential (in moderation) to the rounded human being.' Burgess was, of course, irresponsible enough for two, in fact for a whole benchful of Apostles, but what was Kim's own irresponsibility? At the time I did not ask him what his idea of moderation was, but the thought has often occurred since: was the whole thing, buried under the steely purpose, a lifelong lark? Was what attracted him the nature of the job itself, the idea of having a secret self inaccessible even to his friends, his wives and their former husbands and, as the agent of one intelligence agency inside another, a doubly secret self? Was it not so much the cause, the vision of a 21-year-old never re-examined during a busy spy's life, but a love of deceit and, by extension, of spying itself that kept him at his dead letter drops and secret inks all those lonely years?

I have only a tantalising scrap of evi- dence to offer and now, alas, no way of pursuing it. One liquid Moscow evening Kim asked me, apropos of nothing, 'IC- Kanga, when's your b-birthday?'The first of January,' I told him, as it is. 'Let's have th-th-three hundred grams on that,' said Kim, `s-so's mine,' and he launched kno- wingly into the trials of the date; you never have a party and rarely get a present but you can, on the other hand, readily calcu- late your age to the exact day, a particular- ly useless feat. Then the vodka arrived, flowed, and we got on to other things.

Years later, I was dining with Clare Hollingworth, the intrepid lady war cor- respondent and a Philby friend since the 1930s, at the Marine Press Camp at Da Nang, South Vietnam. Under a tropic sky, to the music of distant gunfire we slapped mosquitoes, sipped Shlitz, the Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous, and dissected mutual friends.

'I know they say Kim is a traitor and all that,' said Clare, 'but I always rather liked him.'

'Me too,' I said, through a mouthful of New Zealand steak.

'We had a tiny bond,' Clare went on. 'It's the kind of silly little thing that brings people together.'

`Oh?'

`We have the same birthday.'

'When's your birthday, Clare?'

`October the tenth. Libra. When's yours?'

So goodbye, Kim. We all miss you, and we hope you have found the workers' paradise. And happy birthday from your friends, whenever it is, and wherever you are. Murrayc Sayle

Previous page

Previous page