Sale-rooms

From Russia with profit

Peter Watson

After all the hoopla of recent months, with Van Goghs and cookie jars hitting the headlines as often as kiss-and-tell memoirs, an auction in Moscow is a distinctly re- freshing change. When it was first announced, there were those in the trade who groaned into their spritzers that it was just another ploy by Sotheby's to drum up trade. Obviously, there is an element of that — and why not? — but Grey Gowrie in London and Simon de Fury in Geneva, who first thought up the deal, made the negotiations and selected the paintings, argue that this is a serious attempt to bring to the West some of the best in Russian art. As evidence of this, Gowrie has said that Sotheby's will print a limited edition of 200 silk scarves based on a design by Varvara Stepanova and a facsimile edition of one of Alexander Rodchenko's sketchbooks 'Monuments', 1982, by Grisha Bruskin which have never been seen in the West, using the proceeds from the sale. All very commendable.

The paintings themselves take some getting used to. They are both familiar and strange at the same time. This is due principally to two reasons. In the first place, almost all the 34 painters repre- sented in the sale have had a thorough academic training. Technically, therefore, they are very competent indeed and, as a result, these Russian works are uniformly deliberate in manner. There is nothing which you feel has just been 'tossed off' in a few moments. Second, having lived in a totalitarian country, these artists have had a system, an entire sociopolitical machine, to kick against. This means that satire, anger and contempt are more evident in their works than what Gowrie calls the 'decorative introspection' of much Western contemporary art. The paintings look out- wards, not inwards.

These factors have also given rise to the presence of a complicated iconography in many of the pictures. Though they are undoubtedly modern in appearance, they also have something of the flavour of 'difficult' mythological Old Masters, where a simple reaction is not enough. The paintings are there to be looked at and read.

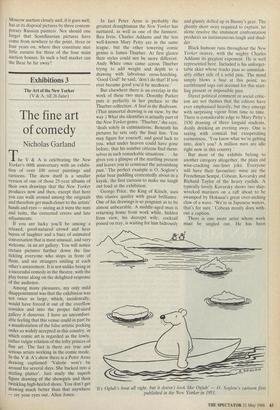

This is most obvious in the works of someone like Grisha Bruskin, who man- ages to produce a kind of Chirico lighting

effect and atmosphere; his figures on plinths mock the monumental and heroic state art of the revolutionary period and at the same time are festooned with objects — cellos, chalices, ships' wheels — the symbolic significance of which gives the works both obvious and hidden meanings. Vadim Zakharov's works have figures half- immersed in blocks of stone, with distorted faces reminiscent of (though nothing like) Bacon and with whole conversations being vomited from their mouths. It sounds awful written down, and it is a bit awful, but it is also an undoubtedly powerful image which calls to mind that Milan Kundera story of the man being sick in the middle of Prague, in Wenceslaus Square, who is comforted by a passer-by. Says the stranger: 'I know just what you mean.'

Other painters, like Leonid Purigin, Nathalie Nesterova or Lev Tabienkin, provide echoes of Miro, Dali, Kossoff or Morandi. Koposkianskaya wraps paper but not like Cristo. Gowrie says he has tried to keep to a minimum the 'nonsense wattage', and though some of these pictures are as conventionally pretty as Sam McCluskie, you do find that, as with difficult old masters (or Sam McCluskie), these Rus- sian works begin to grow on you.

They are mainly in the f2,000–£20,000 bracket, which must put in question whether Sotheby's will make a profit on the deal. With some 150 pictures in the sale at, say, an average price of £6,000, that means Sotheby's will be lucky to earn a commission of £200,000. No wonder they are behaving as a travel company as well, arranging tours to Moscow in conjunction with the sale (they are hoping that the newly renovated Danilov monastery, founded by the son of Ivan the Terrible, will be on the itinerary).

Probably Sotheby's will be content if the venture breaks even. Gowrie believes that the Russians are fanatical collectors. That was certainly true before the revolution, but currency has been a problem ever since. For the July sale, the Russians have demanded 500 tickets and programmes, not a few of which will go to mainstream Politburo members. If they are sufficiently impressed that there is a real market here, then a genuine give-and-take could begin. The Russians are keen, for instance, to buy back a lot of revolutionary art that has leached to the West.

No one seriously imagines we are going to see a repeat of 1931, when Andrew Mellon, then Secretary of the US Treas- ury, bought 21 old masters from the Hermitage for $6.7 million (which would be $141 million now). But Sotheby's (and who can doubt that the other house will soon follow?) would be satisfied with a steady two-way trade. Gowrie doesn't rule out a permanent Moscow office.

That is running ahead somewhat. But Sotheby's timing may be right, and that counts for a lot. At least one major West End gallery, Lefevre, will be watching the Moscow auction closely and, if it goes well, has at its disposal pictures by three contem- porary Russian painters. Nor should one forget that Scandinavian pictures have come from nowhere to the point, three or four years on, where they constitute nice little earners for three of the four main auction houses. In such a bull market can the Bear be far away?

Previous page

Previous page