Exhibitions 1

s Ken Kiff: New Work

(Fischer Fine Art, till 24 June)

Art's child

Alistair Hicks

Kiffs child-like savagery and instant appeal kept him in the wilderness for many years. As he has emerged in the Eighties to critical acclaim, he has reaped the rewards of those long years of questioning. In examining and portraying his own feelings, he discovered a way to analyse and exploit not only his childhood but the whole history of art and thought.

Kiff has been seen as an isolated figure, a self-indulgent regurgitator of dreams, a typical product of Sixties psychoanalysis and a member of the 'funny little men brigade'. This, his first exhibition at Fis- cher Fine Art, demonstrates the out- rageous extent of these lies. He is very much in the mainstream of art. He has long

admitted homage to Klee, Kokoschka, Picasso, Braque and Miro, but 'Large Bird' and 'Blue Man' even invite comparison with the -Expressionism of Kirkner. He is employing a freer, even more immediate technique. 'Blue Man' is literally a heavily outlined blue figure on a white ground with the head displaced horizontally.

Though Kiff is far removed from Francis Bacon in style and content, he disrupts accepted reality in a similar way. He follows a Cartesian model. He destroys, he takes everything back to first principles and then rebuilds, but rather like a volcano or earthquake he often leaves behind the evidence of the process. 'Large Face' is an example. The head had been pulled and stretched apart. A great gap has been filled in with a river of blue. The large Egyptian eye, the gaping mouth and cavernous ear are still part of a whole. They have been disjointed but undergone museum restora- tion. The new and the old, the faults and the original are there clearly to be seen, yet the head becomes one with the world around it. A man walks out of it. There is organic growth from it. A tree stands sentinel in front of the head at point-blank range.

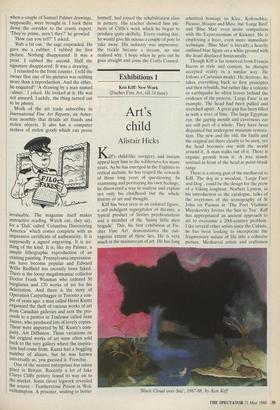

There is a strong gust of the mediaeval in Kiff. The dog in a woodcut, 'Large Face and Dog', could be the design for the prow of a Viking longboat. Norbert Lynton, in his introduction to the catalogue, talks of the overtones of the iconography of St John on Patmos in 'The Poet Vladimir Mayakovsky Invites the Sun to Tea'. Kiff has appropriated an ancient approach to art to overcome a 20th-century problem. Like several other artists since the Cubists, he has been looking to incorporate the fragmentary nature of life into a cohesive picture. Mediaeval artists and craftsmen 'Black Cloud over Sea', 1987-88, by Ken Kiff naturally did this. Everything was brought together under God's roof, literally in His cathedrals. There is a similar consistency in the subject matter of Kiff's paintings. His method of making the picture reinforces this. In 'Snake Telling a Joke', for inst- ance, the three very distinct images of the snake, the skull scratching its head and the laughing man are brought together by being rooted in the colour scheme of the earth. They grow out of it.

'Black Cloud over Sea', where a satanic cloud eats into the bright pink sky, reaf- firms Kiff's reputation as a rapturous col- ourist, yet many of the works on display are in reduced colouring. There is a curious experimentation in some of the woodcuts. 'Man and Fish' is subdivided as simply as early calendars of the four seasons. He has a near contemptuous ease with colour. In a drawing of mainly brown and black char- coal and pastel, 'Sun above Man in Boat', he allows a bright rainbow to weave itself in and out of the cloud and sun. It echoes the action below where a fulsome one-eyed coquette throws open a window. The frog-like man in the boat beneath may have passed by, but the look in his one large eye is totally absorbed by the invita- tion. Besides, his amorphous body has practically crept up the wall of its own volition.

The inclusion of drawings and woodcuts proves that Kiff doesn't need colour to cast his enchantment. They also underline his proximity to Munch. His is a thorough exploration of psychological intensity.

Kiff has lived through an age of anxiety. It has provided him with much of the vocabulary for his paintings. Yet as Nor- bert Lynton writes, 'Anxieties are trans- cended as we meet our many selves in his art.' The only limits to his subject matter are those of the human brain and heart. He is a pied piper and everyone listening can hear their own tune. He uses his wealth of art-historical knowledge as naturally as art's child.

Previous page

Previous page