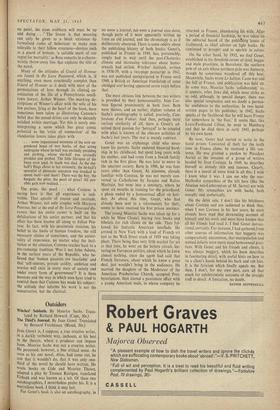

Outsiders

JEAN GENET is, I suppose, a true creative writer, in a darkly turbulent way, inchoate, at his best in the theatre, where a producer can impose form. Maurice Sachs was not a creative writer. He possessed, however, a fine critical sense. As soon as his one novel, Alias, had come out, he saw that it wouldn't do, that it was only one- third of the novel he should have written. He wrote books on Gide and Maurice Thorez, adapted a play by Terence Rattigan, translated Firbank and was known as a wit. Of these two autobiographies, I nevertheless prefer his. It is a marvellous book. I think it may last.

For Genet's book is also an autobiography, in

no sense a journal, not even a journal sans dates, though parts of it were apparently written up from an old journal, and the chronology is as if deliberately obscured. There is some oddity about the publishing history of both books. Genet's, published in France in 1949, has, presumably, simply had to wait until the post-Chatterley climate and increasing tolerance about homo- sexuals had settled. Witches' Sabbath, written in 1938-39, with a two-page postscript in 1942, was not published unexpurgated in France until 1960, a British or American translation of some abridged text having appeared seven years before that.

The most obvious link between the two writers is provided by their homosexuality. Jean Coc- teau figured prominently in both lives. Both were thieves, and an earlier, slighter volume of Sachs's autobiography is called, precisely, Con- fessions d'un Voleur. And then, perhaps most curious similarity of all, there is Genet's ad- mitted third passion for 'betrayal' to be coupled with what is known of the obscure activities of Sachs's last years. The rest is mainly contrast.

Genet was an orphanage child who never knew his parents. Sachs endured financial hard- ship in his childhood, but spent long years with his mother, and had come from a Jewish family rich in the first place. He was later to move in the smartest society. Born in 1906, he was four years older than Genet. At nineteen, already familiar with Cocteau, he was not merely con- verted to Catholicism by Jacques and Raissa Maritain, but• went into a seminary, where he spent six months in training for the priesthood, a phase ended by a homosexual affair on holi- day. At about this time, Genet, who had already been sent to a reformatory for theft, seems to have received his first prison sentence.

The young Maurice Sachs was taken up for a while by Mme Chanel, buying rare books and bibelots for rich clients on the side. Then fol- lowed his fantastic American interlude. He arrived in New York with a load of French art just as the Wall Street crash of 1929 was taking place. There being thus very little market for art at that time, he went on the lecture circuit, lec- turing on European politics, about which he knew almost nothing, since the agent had said that French literature, about which he knew a great deal, just wouldn't bring in the audiences. He married the daughter of the Moderator of the American Presbyterian Church, accepted Pres- byterianism, then started a passionate affair with a young American male, in whose company he

returned to France, abandoning his wife. After a period of financial hardship, he was taken on the editorial board of the publishing house of Gallimard, as chief adviser on light books. He continued to prosper and to sparkle in salons.

On the other hand, by 1932, we find Genet, established in his threefold career of thief, beggar and male prostitute, in Barcelona, the southern pole of an axis whose northern pole was Antwerp, though he sometimes wandered off this beat. Meanwhile, Sachs wrote Le Sabbat. Came war and the fall of France, and publication was held up. In some way, Maurice Sachs 'collaborated,' as, it appears, other Jews did, which must strike us as odd, although, in special danger, there was also special temptation and no doubt a particu- lar usefulness to the authorities. In two -hand- written pages to his publisher, in 1942, Sachs speaks of the likelihood that he will leave France for somewhere in 'the East.' It seems that, like Louis-Ferdinand Celine, he went to Hamburg and that he died there in early 1945, perhaps by his own hand.

By now, Genet had started to write in the Sante prison. Convicted of theft for the tenth time in France alone, he received a life sen- tence. He was granted a pardon by President Auriol at the instance of a group of writers headed by Jean Cocteau. In 1949, he describes himself as already rich and famous. Clearly, there is a moral of some kind in all this. I wish I knew what it was. I can see why the neo- Methodist sympathies of the left here (like the Alsatian neo-Lutheranism of M. Sartrc) are with Genet. My sympathies are with Sachs, both morally and msthetically.

On the debit side, I don't like his bitchiness about Cocteau and am saddened to think that, when 1 met Cocteau in his last years, he must already have read that devastating account of himself and his work and must have known that all his friends had read it. I find Genet instruc- tional, certainly. For instance, I had gathered,from other sources of information that buggery was comparatively uncommon, that manipulation and mutual fellatio were more usual homosexual prac- tices. With Genet and his friends and clients, it was always buggery, which his book describes in fascinating detail, with useful hints on how to tie a client's hands behind his back and rob him. It is the lyricism which finally appals me. But then, I don't, for my own part, care all that much for exhibitionistic accounts of the straight stuff in detail. A limitation, no doubt.

RAYNER HEPPENSTALL

Previous page

Previous page