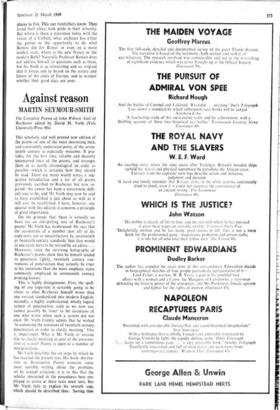

Against reason

MARTIN SEYMOUR-SMITH

This scholarly and well printed new edition of the poems of one of the most interesting men, and consistently underrated poets, of the seven- teenth century is especially welcome. It pro- vides, for the first time, reliable and decently uncensored texts of the poems, and arranges them in as nearly chronological an order as possible—which is certainly how they should be read. There are many useful notes, a sug- gestive introduction and a list of all poems previously ascribed to Rochester but now re- )ected—his canon has been a notoriously diffi- cult one to fix, and Mr Vieth may now be said to have established it just about as well as it will ever be established. 1 have, however, one quarrel with this edition; it concerns a principle of great importance.

On the grounds that 'there is virtually no basis for an old-spelling text of Rochester's poems' Mr Vieth has modernised. He says that the accidentals of a number (not all) of his copy-texts are so unsatisfactory by seventeenth or twentieth century standards 'that they would in any event have to be revised by an editor.... Moreover, since the surviving holographs of Rochester's poems show that he himself tended to punctuate lightly, twentieth century con- ventions of punctuation may actually be truer to his intentions than the more emphatic styles commonly employed in seventeenth century printing-houses.'

This is highly disingenuous. First, the spell- ing of any copy-text is certainly going to be closer to what Rochester himself wrote than any version standardised into modern English; secondly, a highly sophisticated, wholly logical system of punctuation, such as we now use, cannot possibly be 'truer' to the intentions of one who wrote when such a system did not exist. Mr Vieth frankly admits that he wished 'to command the resources of twentieth century punctuation in order to clarify meaning.' This is impertinent. Who is Mr Vieth or anyone else to clarify meaning as part of the presenta- tion, of a text? Poetry is open to a number of interpretations.

Mr Vieth describes the six steps by which he has reached the present text. His book Attribu- tion in Restoration Poetry contains some most sensible writing about the problems set, by textual criticism; it is to this that the scholar interested in the procedures here em- ployed to arrive at these texts must turn. But Mr Vieth fails to explain his seventh step, which should be described thus: 'having thus

reached a satisfactory text, I emend each word (that requires it) by modernising, and super- impose on the whole my own interpretation of the meaning by the use of a punctuation-system unknown to the author.' That is what moderni- sation involves: let us make no mistake about it. My view is that we do scant justice to our re- gard for a writer by trying to create him in our own image.

Thus, inaccurate though it may be (Mr Vieth says it is), we need to keep our Muses Library edition of Rochester about us, for it does give us the spelling of Rochester's holographs and the early versions of his poems that derived from them.

Mr Vieth is very much more satisfactory when he is discussing the nature of Rochester's poetic genius. As he suggests, Rochester was peculiarly 'modern' in his pressing concern with questions of identity. Born in 1647, he learned to drink and whore very early, though he differed from his age not in being profligate but in pondering so deeply upon the nature and ultimate meaning of his profligacy. He was dead at thirty. He was supposed to have passed some two years perpetually drunk; one can nearly believe it, for it may well have been his extraordinary intelligence (only Etherege of the so-called Restoration wits came near to approaching him in this) reluctantly witnessing the vagaries of his drunken self-indulgence that first made him aware of the problems posed by human identity. In any case, as Mr Vieth points out, the structure of such a poem as 'Artemisia to Chloe' simply illustrates the multiplicity of assumed identities . . . used by Rochester as speakers in his poems, thereby raising the philo- sophical question of identity which has been such an insistent concern in the twentieth cen- tury. . . . To a greater or lesser degree the "1" of each poem is always Rochester, even when the speaker is a woman.'

This is some of the best criticism ever made of Rochester, and helps to explain why the reading of all his poems together, and in roughly the order he wrote them, is such an overwhelming and tragic experience. Not much he wrote, with the exception of a few squibs, is merely trivial or merely silly. In character he anticipated Swift—no other English poet could have written the song 'Fair Chloris in a Pigsty Lay'—but he could look back to an era of straightforward love-poetry, which Swift could not. It was Rochester, too, in 'An Allusion to Horace, the Tenth Satyr of the First Book,' who began the fruitful English tradition of the 'imitation.' His opinions of his contemporaries as evinced in this poem are shrewd and well-balanced. Dr Leavis has always rather feebly insisted that there is 'a line of wit' leading from Donne through Rochester to Pope. But the line, which com- bines wit with savage puritanism and zest for life leads to Swift rather than to Pope, as those who can smell the midnight oil that pervades the poems of the latter will recognise.

One of the chief influences on Rochester in 'A Satyr against Reason and Mankind,' as sub- stantial a poem as any written in its decade, along with Boileau (upon whose eighth satire it is very loosely based) and Hobbes, is Mon- taigne, whose nobility of spirit it is easy to see he appreciated. But one of the less obvious aspects of 'A Satyr' is the way in which the hedonistic element in Rochester's scepticism (which was so extreme that it may fairly be decribed as Pyrrhonistic) robbed him of the 'imperturbability' that it was traditionally sup- posed to produce. This concern is present in the structure and the language of the poem, just as self-disgust is an evident theme of all Rochester's more serious poems.

And yet his famous and suspiciously dramatic death-bed conversion makes no sense at all in terms of his work, delightfully though Burnet describes it; perhaps Rochester was simply too tired and too ill to continue to avoid senti- mentality—in any case, as Mr Vieth writes, it may only be judged 'in the privacy of a man's soul.' Of more relevance in Burnet's account are the details about Rochester's real-life prac- tice of adopting disguises—matching the various personae adopted in his poems: 'He took pleasure to disguise himself, as a Porter, or as a Beggar; sometimes to follow some mean Amours. . . . At other times, merely for diver- sion, he would go about in odd shapes, in which he acted his part so naturally, that even those who were in the secret . . . could perceive nothing by which he might be discovered.'

Mr Vieth's edition gives us a new and sub- stantial opportunity to study the work of the most fascinating and important poet of his time; it should shortly be seen that Rochester, not Dryden, stood at the centre of the truly poetic scene in Restoration England.

Previous page

Previous page