The ancestor of concrete

Charles Saumarez Smith

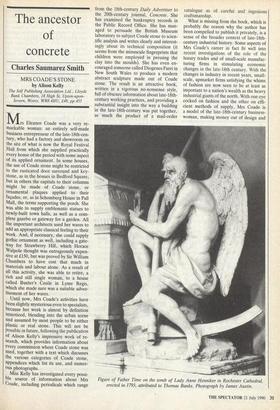

MRS COADE'S STONE by Alison Kelly Mrs Eleanor Coade was a very re- markable woman: an entirely self-made business entrepreneur of the late-18th-cen- tury, who had a factory and showroom on the site of what is now the Royal Festival Hall from which she supplied practically every house of the period with some aspect of its applied ornament. In some houses, the use of Coade stone might be restricted to the rusticated door surround and key- stone, as in the houses in Bedford Square; but in others the capitals to their columns might be made of Coade stone, or ornamental plaques applied to their façades, or, as in Schomberg House in Pall Mall, the terms supporting the porch. She was able to supply emblematic statues to newly-built town halls, as well as a com- plete gazebo or gateway for a garden. All the important architects used her wares to add an appropriate classical feeling to their work. And, if necessary, she could supply gothic ornament as well, including a gate- way for Strawberry Hill, which Horace Walpole thought was outrageously expen- sive at £150, but was proved by Sir William Chambers to have cost that much in materials and labour alone. As a result of all this activity, she was able to retire, a rich and still single woman, to a house Called Bunter's Castle in Lyme Regis, which she made sure was a suitable adver- tisement of her wares.

Until now, Mrs Coade's activities have been slightly mysterious even to specialists, because her work is almost by definition unnoticed, blending into the urban scene and assumed by most people to be either plastic or real stone. This will not be possible in future, following the publication of Alison Kelly's impressive work of re- search, which provides information about every commission where Coade stone was used, together with a text which discusses the various categories of Coade stone, appendices which list its use, and numer- ous photographs.

Miis Kelly has investigated every possi- ble source of information about Mrs Coade, including periodicals which range The Self Publishing Association Ltd., Lloyds Bank Chambers, 18 High St, Upton-upon- Severn, Wows, WR8 4HU, £48, pp.455 from the 18th-century Daily Advertiser to the 20th-century journal, Concrete. She has examined the bankruptcy records in the Public Record Office. She has man- aged to persuade the British Museum laboratory to subject Coade stone to scien- tific analysis and writes clearly and interest- ingly about its technical composition (it seems from the minuscule fingerprints that children were employed in pressing the clay into the moulds). She has even en- couraged someone called Diogenes Farri in New South Wales to produce a modern abstract sculpture made out of Coade stone. The result is an attractive book, written in a vigorous no-nonsense style, full of obscure information about late-18th- century working practices, and providing a substantial insight into the way a building in the late-18th-century was put together, as much the product of a mail-order catalogue as of careful and ingenious craftsmanship.

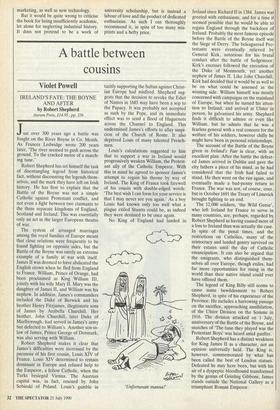

What is missing from the book, which is probably the reason why the author has been compelled to publish it privately, is a sense of the broader context of late-18th- century industrial history. Some aspects of Mrs Coade's career in fact fit well into recent investigations of the role of the luxury trades and of small-scale manufac- turing firms in stimulating economic changes in the late-18th century. With the changes in industry in recent years, small- scale, upmarket firms satisfying the whims of fashion are now seen to be at least as important to a nation's wealth as the heavy industrial giants of the north. With one eye cocked on fashion and the other on effi- cient methods of supply, Mrs Coade is a model of the late-18th-century business- woman, making money out of design and Figure of Father Time on the tomb of Lady Anne Henniker in Rochester Cathedral, erected in 1793, attributed to Thomas Banks. Photograph by James Austin. marketing, as well as new technology.

But it would be quite wrong to criticise the book for being insufficiently academic, let alone for neglecting industrial history. It does not pretend to be a work of university scholarship, but is instead a labour of love and the product of dedicated enthusiasm. As such I can thoroughly recommend it, in spite of too many mis- prints and a hefty price.

Previous page

Previous page