The day of the Indictment

Airey Neave

What better place could the Allies have chosen for the trial of Goering and other top Nazis than Nuremburg itself? In 1945, Rebecca West described the city as 'The World's Enemy'. Was it not here that Hitler's savage oratory had lashed millions of ordinary Germans into racist frenzy ? In October of that year, I stood on the Zeppelin Field where the huge rallies of the Nazi Party had been held. It was here that Speer's colossal swastika banners with a hundred and thirty searchlights formed (in his own words) a 'cathedral of light'. I tried to imagine the pageantry of Nazi Nuremburg, though the place was now a GI sports ground. Nailed to the framework of the platform from which Hitler had spoken was another banner with the words 'Soldier's Field'.

It was this victory of the Common Man that the Western Allies hoped to consolidate by the coming trial. They set out with high hopes of strengthening international law so that war and its inhumanities could be prevented. They aimed to protect the civilian and the prisoner of war from further outrage. The Soviet delegation drank each night to the death of the Hitlerite murderers now in the Nuremburg prison. Their judges envisaged no acquittals.

In October 1945 the eyes of the world

turned to Nuremburg and the International Military Tribunal set up in Berlin by the American, British, French and Russian governments. Germany's surrender in May, revealing those piles of naked moon-white corpses, brought loathing and horror. I was appalled at what Hitler had brought to Nuremburg, the town of working toys and gingerbread, of Dfirer and Veit Stoss, the great wood-carver. There was a sickening smell of disinfectant from the mounds of stone and splintered wood which covered six thousand corpses. Against the old city wall, one of the round mediaeval gatetowers leaned precariously. In an upper chamber a feeble candle burned each night. This was all that remained of the arts of peace for which Nuremburghad once been famous.

In 1945, people remembered that the town had given its name to the laws by which Jews were deprived of their rights as citizens. At the Zeppelin Field, Hitler had declared that anti-semitism was 'a new creed for the masses'. The awful 'Final Solution' of the Jewish problem and the Nazi Revolution of Destruction seemed to begin and end at Nuremburg.

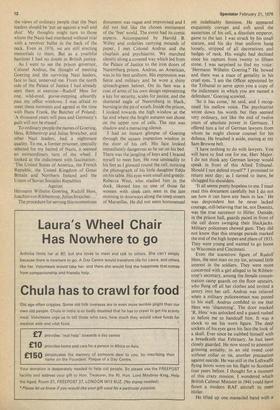

The Palace of Justice where the trial was to be held was a solid municipal building on the FOrtherstrasse. It was fortified by five Sherman tanks with 76-mm guns to prevent any rescue attempt by the SS of the leading Nazis in the adjoining prison. Inside the courtyard and in the wide corridors were American troops with machine-guns, crouched behind sandbags. Sentries in the prison were armed with automatic weapons and grenades. Strong was the fear of the SS still hidden in the black ruins. Anonymous warnings were received that the attack would be led by Martin Bormann. Secretly, I looked forward to this battle: but it never came.

When I arrived from collecting evidence against Krupp at Essen, the courtroom was being enlarged. Beneath its florid chandeliers and baroque clock, the Nazis had tried those who dared to conspire against Hitler. Now it was as if the last act was played out. The Allied conquerors, besieged in the desolation of Nuremburg, spent their evenings in the Grand Hotel on the Bahnhofplatz. Appointed an official of the British delegation, I was there on October 17 when a group of distinguished Americans bore down on me in the foyer. Their leader was Francis Biddle, former Attorney-General of the United States and now the principal American judge of the International Military Tribunal. His sardonic smile was forbidding. He addressed me in a nasal voice. 'You Major Neave?' 'Yes.' You look remarkably young. Are you ready tomorrow afternoon to serve the indictment of the defendants in their cells?'

I must have looked alarmed. It seemed to me a most dangerous situation; I had known nothing like it since Colditz. I do not know why no orders had reached me. There seemed to be no communication between the different delegations. Only next morning was I given twenty-one copies of the massive indictment by Mr Harold B. Willey, the General Secretary of the Tribunal. It had been published in Berlin, but the American, British, French and Russian judges had not fixed the date of the trial. 'They want November Twenny', 'said Mr Willey', 'though Gawd knows ...'

Article 16 of the Charter of the Tribunal provided that a copy of the indictment should be 'furnished' to each defendant before the trial by an officer appointed for the purpose. Since I was that officer, I was also instructed to explain to each defendant his right to a `fair trial'. The traditions of the Temple ruled at Nuremburg, whatever

the views of ordinary people that the Nazi leaders should be 'put up against a wall and shot'. My thoughts might turn to those whom the Nazis had murdered without trial with a revolver bullet in the back of the neck. Even in 1976, we are still erecting memorials to them. But as a youthful barrister I had no doubt in British justice.

As I went to see the prison governor, Colonel Andrus, the thought of meeting Goering and the surviving Nazi leaders, face to face, unnerved me. From the north side of the Palace of Justice I had already seen them at exercise—Rudolf Hess for one, wild-eyed, goose-stepping absurdly past my office windows. I was afraid to meet these monsters and agreed at the time with Hans Frank, the Butcher of Poland: 'A thousand years will pass and Germany's guilt will not be erased'.

To ordinary people the names of Goering, Hess, Ribbentrop and Julius Streicher, and other Nazi leaders, had a nightmare quality. To me, a former prisoner, specially selected for my hatred of Nazis, it seemed an extraordinary turn of the wheel. I looked at the indictment with fascination : 'The United States of America, the French Republic, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Against Hermann Wilhelm Goering, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ri bbentrop, Julius Streicher ...' The procedure for serving this momentous

document was vague and improvised and I did not feel like the chosen instrument of the 'free' world. The event had its comic aspects. Accompanied by Harold B. Willey and orderlies carrying mounds of paper, I met Colonel Andrus and the chaplain and psychiatrist. We marched silently along a covered way which led from the Palace of Justice to the iron doors of Nuremburg prison. Andrus, an American, was in his best uniform. His expression was fierce and military and he wore a shiny spinach-green helmet. On its face was a coat of arms of his own design representing a key for security, scales for justice, and the shattered eagle of Nuremburg in black, burning in the pit of wrath. Inside the prison, I looked towards the high window at the far end where the bright autumn sun shone on the upper row of cells. The rest was shadow and a menacing silence.

I had an instant glimpse of Goering through the square inspection window in the door of his cell. His face looked immediately dangerous as he sat on his bed. There was the jangling of keys and I braced myself to meet him. He rose unsteadily to his feet as I glanced round the cell, noticing the photograph of his little daughter Edda on his table. His eyes were small and greedy. Rebecca West, who studied him in the dock, likened him to one of those fat women with sleek cats seen in the late morning in doorways along the steep streets of Marseilles. He did not seem homosexual

yet indefinably feminine. He appeared exquisitely corrupt and soft amid the austerities of his cell, a dissolute emperor, game to the last. I was struck by his small stature, and his sky blue uniform hung loosely, stripped of all decorations and badges of rank. His weight had declined since his capture from twenty to fifteen stone. I was surprised to find my voice: 'Hermann Wilhelm Goering?' He bowed and there was a trace of geniality in his cruel eyes. 'I am the Officer appointed by the Tribunal to serve upon you a copy of the indictment in which you are named a defendant.' Goering scowled.

`So it has come,' he said, and I recognised his mellow voice. The psychiatrist wrote down his words but they seemed very ordinary, not like the end of twelve years of absolute power in Germany. I offered him a list of German lawyers from whom he might choose counsel for his defence. He brushed it aside, staring at my Sam Browne belt.

'I have nothing to do with lawyers. You will have to find one for me, Herr Major. I do not think any German lawyer would speak in front of this Allied Tribunal. Should I not defend myself?' I promised to return next day; as I turned to leave, he shrugged his shoulders.

'It all seems pretty hopeless to me. I must read this document carefully but I do not see how it can have any basis in law.' He was despondent but he never lacked courage, still, believing that he, not Doenitz, was the true successor to Hitler. Outside, in the prison hall, guards paced in front of the cell doors swinging their blackjacks. Military policemen chewed gum. They did not know that this strange parade marked the end of the high hopes and plans of 1933. They were young and wanted to go home to Wisconsin and Cincinnati.

Even the scarecrow figure of Rudolf Hess, the next man on my list, aroused little interest in the soldiers. They were more concerned with a girl alleged to be Ribbentrop's secretary, among the female concentration camp guards on the floor upstairs, who flung off all her clothes and invited a sentry into her cell. Andrus was relieved when a military policewoman was posted to his staff. Andrus confided to me that Hess was 'shamming'. The door marked 'R. Hess' was unlocked and a guard rushed in before me to handcuff him. It was a shock to see his worn figure. The deep sockets of his eyes gave his face the look of a skull. Ever since he stabbed himself with a breadknife that February, he had been closely guarded. He now stood to attention grinning amiably, in an old tweed coat without collar or tie, another precaution against suicide. He was still in the Luftwaffe flying boots worn on his flight to Scotland four years before. I thought for a moment of this crazy mission. I wondered which British Cabinet Minister in 1941 could have flown a modern RAF aircraft to meet Hitler.

He lifted up one manacled hand with a

mischievous smile and said nothing when I spoke to him. The indictment was put on his bed. When the handcuffs were removed he sat down and resumed his reading of Brideshead Revisited. There had been no sign of serious mental disturbance, his condition varied daily. That night he was found in a state of total amnesia. He could only write, in English, on a copy of the indictment :

'I can't remember.'

If Hess was macabre, Ribbentrop—the 'Second Bismarck'—was scruffy. Goering and Hess were soldiers, and both showed courage. Ribbentrop, vain as a peacock according to Goering, was filled with selfpity. His cell was a mess. I could hardly believe that here was the arrogant Ambassador to London before me. He seemed nervous and irresolute, and I was surprised to learn that he had fought through the First World War and won an Iron Cross. He spoke to me, half-sobbing: 'What am I to do ? Where can I find a lawyer ?' The pleading in his salesman's voice embarrassed me. Then he handed me a list of aristocratic British names: 'Evidence of my desire for peace,' he said in a deep baritone. For a moment, he was Hitler's Foreign Minister, but when the door was again locked, I saw him through the window. He stood there, helpless, with his list of titled witnesses.

Next on my list was the Beast of Nuremburg, Julius Streicher. At first sight he was short and insignificant, wearing a khaki shirt and trousers. The Jewish interpreter aroused him to fury until Andrus told him to stand to attention. Then he turned on me with his pig eyes. 'The Herr Major is not a Jew'. Andrus brandished his stick at him and barked for silence.

The man was primarily a sex criminal looking like the subject of an obscure seventeenth century woodcut. One of his convictions was for ,indecently assaulting a boy prisoner whilst on a visit, as Gauleiter of Franconia, to these very cells. He represented for me all that was most revolting in Nazism. His was the worst name in all the world. It is easy to dismiss him as the sort of dirty old man who gives trouble in parks. At the height of his influence in the Nazi party, millions followed his creed of hate. Without him, Hitler might never have carried through the 'Final Solution'. He ended as he began at Nuremburg. He was hanged and his body burned in the ovens of Dachau. His head was shaped like a bullet with a sharply receding forehead. He looked like a professional torturer who might have operated the famous Iron Maiden of Nuremburg now buried in the ruins.

'I am told the judges are all Jews,' said Streicher, the veins swelling in his forehead. What could one say? I looked down at the filthy old man and shook my head. The American prosecution had shown me the Photograph of a beautiful young Jewish girl stripped for the gas chamber and about to die. We had come too late. There were no lights in the cells at that time and, as the afternoon wore on, it was difficult to see the expressions of the remaining prisoners. Few of them had much to say to me. I afterwards discovered that, not believing the Allies would give them a 'fair trial', many thought I had come to announce a summary court-martial. In the next month I advised them all—Keitel, Doenitz, Schacht and the others—about rights of defence and obtained lawyers to represent them from all over Germany.

Was it worth while? If during the next year the Tribunal had not heard evidence of their terrible crimes against humanity, history would never have recorded them. The trial ended in September 1946, when the world began to tire of it : but for me the most important was always the day of the indictment eleven months before.

Previous page

Previous page