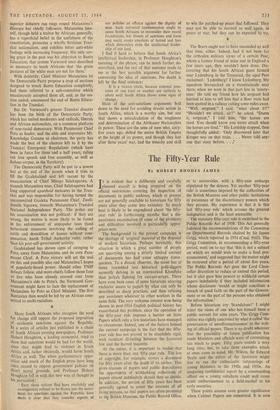

Notes from a Refugee

By RANDOL PH VIGNE

(Mr. Vigne arrived in England on August 13, having escaped arrest and a banning and con- fining order in South Africa, where the police were searching for him most of July. Before being banned he was national vice-chairman of the Liberal Party of South Africa. He was

_ also joint-editor of the Monthly The New African and was active in other publishing and journalistic fields.) OF South Africa's 16,000,000 people, the Johannesburg Star wrote recently, 'a minority are engaged in a political war across the

colour line.' This is indisputable. 'The thing that preserves the country's equilibrium and keeps it in production is the huge mass of orderly and on the whole racially co-operative people in be- tween.' Perhaps the visitor to South Africa would not dispute the second qentence either, after seeing so many smiling black faces mingling with sad, grim white ones in the streets. At the airport, or petrol station, or in the hotel lobby, the Africans appear courteous and cheerful, even if the term 'racially co-operative' is not quite borne out by the sharp manner of speech or cold looks of their white superiors addressing them.

Yet the visitor steadily gains sympathy for the white South Africans he meets, since they have so much to lose by handing their country over to untrained Africans, and his sympathy for what he had believed to be the latter's aspirations ebbs away as he becomes more and more convinced that the Africans not only accept white rule, but actually appreciate its benefits.

The supporting evidence is quickly collected: African housing is adequate, there is no real starvation, welfare services excel those in many backward countries,- the younger children are going to school in large numbers, and the courts are said to be impartial. Not only do the Afri- cans not revolt against white rule; they do not appear to have much reason to want to do so.

If the visitor can be so deceived, how much more readily the Star's leader-writer, since he

has so much greater cause for wanting to believe these things? The good-humoured outward man- ner of these ulcer-free 'descendants of the Bantu-

speaking tribes of southern Africa,' as the 11,000,000 'Bantu' at the bottom of the pile are called, is as faulty evidence of their contentment as are the other items (which neither the visitor nor the leader-writer has actually seen).

On the attitude of this majority depends the success of any concerted movement inside or outside the country to change the present un- acceptable system.

The politically-warring minority do not, indeed, have the support of the mass : South African leaders are not accorded the veneration long re- ceived by Dr. Banda or Dr. Nyerere in their countries; the name Lumumba is probably more of a household word in South Africa than Sobukwe, Luthuli or Mandela. Can this be because the Republic's African community has less confidence in the methods these leaders have advocated than Malawians had in Dr. Banda or Tanganyikans in Dr. Nyerere? It is puzzling, but should not be really disturbing to those who recognise the South African system as an evil anachronism and wish for its replacement.

The fact is that these millions of seemingly co- operative men and women have clearly defined common grievances—above all, low wages, the pass laws and Afrikaner Nationalist rule--which cause them increasingly to Share the urge for change that the political leaders have worked for with such moderate success.

It is no doubt true that quite small concessions in wage scales and in the implementation of the pass laws might reconcile the mass to Afrikaner Nationalist rule for a further period. The reverse is what is happening. White prosperity in the current economic boom makes the gap in wealth between the races wider than ever; the new Bantu Laws Amendment Act (1964) will increase the heavy burden of the pass laws for every indi- vidual African. And most significantly of all, the English-speaking South Africans, by their new support of Afrikaner Nationalist rule, are making an alternative, moderated form of white rule seem unattainable to those Africans who have hitherto shrunk from opposing white supremacy as such.

The political war across the colour line may continue to be fought by a minority and fought, from the African side, under increasing diffi- culties. The new circumstances—boom, more repression, white unity—make the support of the mass for this minority likely for the first time.

This once again brings into view the type of almost spontaneous, largely unorganised mass action by Africans which last brought parts of the country to a standstill during the post- Sharpeville Anti-Pass Campaign of 1960, or the Defiance Campaign of 1952.

*

How can such action take place? Both the Pan-Africanist Congress, who led the 1960 affair, and the African Nationalist Congress, who led in 1952, are now effectively proscribed. There are over 900 political prisoners on Robben Island, the one hundredth official of the largely African SA Congress of Trade Unions was banned recently, and a high proportion of other poten- tial participants are either banned, house arrested, exiled or have been threatened into in- • activity. I do not know any answer to this. I know that African political advances follow no rules, the South African situation is sui generis and makes nonsense of the theories of the students of revolution.

Mr. Patrick Duncan, in the Cronkite television film Sabotage in South Africa, last year called Dr. Verwoerd 'the demolition hammer in the hand of God.' Inasmuch as it takes two to make a revolution, the Doctor is doing his work well, along the lines indicated by Mr. Duncan's phrase. He is probably functioning nowhere better than in the Transkei State.

To buy off United Nations pressure in 1961- 62, this portion of the eastern Cape Province was given its own constitution; 2,000,000 Xhosa- speaking Africans live there, and only about 20,000 whites and coloureds. In the ensuing elec- tions the Government-supporting party, led by a regional chief, Kaizer Matanzima, was soundly defeated by Paramount Chiefs Sabata Dalindyebo and Victor Poto's anti-apartheid opposition.

The constitution allowed for sixty-four ex- officio chiefs in a legislative assembly of 109, and their almost solid pro-Government vote—all are civil servants--put Matanzima and his col- leagues in power.

The first session, earlier this year, brought con- stant embarrassment to the Republican Govern- ment, as the opposition Democratic Party's vastly superior debaters ran rings round Matanzima's illiterate but chiefly followers. Matanzima him- self, though held a traitor by Africans generally, has a superficial belief in the usefulness of the constitution, promotes a wholly fictitious Tran- skei nationalism, and exhibits bitter anti-white feelings with increasing frequency. His only sav- ing grace in the past was his objection to Bantu Education, that system Verwoerd once described as necessary to teach Africans that 'the green pastures of the white man are not for them.'

With dexterity, Chief Minister Matanzima let the Democratic Party propose a crop of motions designed to wreck Bantu Education completely, had them referred to a sub-committee which unanimously accepted them all, and, as the ses- sion ended, announced the end of Bantu Educa- tion in the Transkei.

But Dr. Verwoerd's greater Transkei disaster has been the birth of the Democratic Party, which has united moderates and radicals, liberals and African nationalists, on a common platform of non-racial democracy. With Paramount Chief Poto as leader, and the able and impressive Mr. Knowledge Guzana as chairman, the party has made the best of the chances left to it by the Transkei Emergency Regulations (which have been in force for three and a half years, ruling out free speech and free assembly, as well as habeas corpus, in the Territory).

The Democratic Party will be put to a severe test at the end of the month when it tries to fill the Gcalekaland seat left vacant by the assassination of Chief Mlingo Salakupatwa. A staunch Matanzima man, Chief Salakupatwa had long supported apartheid measures in the Tran- skei and was responsible for having turned the uncommitted Gcaleka Paramount Chief, Zweli- dumile Sigcawu, towards Matanzima's Transkei National Independence Party. The police say his assassination was not political : if they are Wrong, the motive is more likely to be found in his enforcement of unpopular laws (land betterment measures involving the culling of cattle and demolition of homes without com- pensation, harsh Tribal Authority rule), rather than his post-self-government activity.

Gcalekaland has shown signs of swinging to Poto, away from Matanzima and its own Para- mount Chief. A Poto victory will set the seal on this and possibly also end Matanzimal hopes of popularly-based power. Should other TNIP defeats follow, and more chiefs follow those four or five who have already crossed over from Matanzima's side to Poto's, the Verwoerd Gov- ernment might have to face the replacement of Matanzima by Poto as Chief Minister. The first Bantustan then would be led by an African com- mitted to multi-racialism.

* Many South Africans who recognise the need for change still oppose the proposed imposition of economic sanctions against the Republic. In a series of articles just published in a chain of South African evening newspapers, Professor Hobart Houghton, a leading economist, tried to show that sanctions would be bad for the world, since they might lead to violence in South Africa and, rather obviously, would harm South Africa as well. The white parliamentary oppo- sition and much of the English press have long since ceased to oppose government policies on direct moral grounds, and Professor Hobart Houghton fell in with this new way of thought in his peroration : Even those nations that have resolutely and courageously refused to be drawn into the move- ment for sanctions against the Republic have made it clear that they consider aspects: of our policies an offence against the dignity of man. Such universal condemnation ought to cause South Africans to reconsider their moral foundations, but threats of sanctions and force may easily evoke emotions of hatred and fear which demoralise even the intellectual leader- ship of our land.

I find it hard to believe that South Africa's intellectual leadership, in Professor Houghton's meaning of the phrase, can be much further de- moralised, and the rest of that sentence reads to me as the best possible argument for further canvassing the idea of sanctions. No doubt is left by the final sentence: It is a vicious circle, because external pres- sures of one kind or another are unlikely to abate until South Africa shows some signs of change.

Most of the anti-sanctions arguments boil down to the need for avoiding drastic action in South Africa, which is a worthy aim, but one that shows a miscalculation of the toughness and determination of the Afrikaner Nationalists in power. These are the sons of men who, sixty- five years ago, defied the entire British Empire at the height of its power, and though they lost after three years' war, had the tenacity and skill to win the patched-up peace that followed. They may not be able to succeed so well again, in peace or war, but they can be expected to try,

The Boers ought not to have succeeded so well that time, either. Indeed, had it not been for the orthodox military views of a certain Peer, whom a farmer friend of mine met in England a few years ago, they wouldn't have done. Dis- covering that his South African guest farmed near Lydenburg in the Transvaal, the aged Peer exclaimed: Tydenburg I I know Lydenburg. My squadron bivouacked on a mountainside near there, when we were in that part late in 'ninety- nine.' He told my friend how his sergeant had hurried to him to tell him that a Boer train had been spotted in a railway cutting some miles away. "'Well, sergeant," I said, "what about it?" "Shouldn't we attack, sir?" he asked. "Damn it, sergeant," I told him, "the horses are tired. You should know you never attack when the horses are tired." ' His Lordship stopped, then thoughtfully added : 'Only discovered later that Kruger was on that train. . . . Never told any- one that story before. . .

Previous page

Previous page