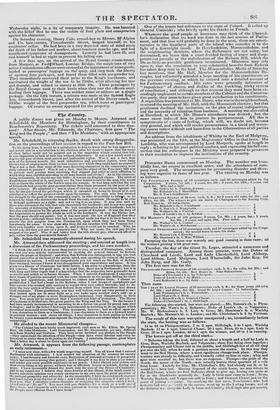

Countre.

A public dinner was given on Monday to Messrs. Attwood and Scholefield, the Members for Birmingham, by their constituents in Beardsworth's Repository. The tickets sold amounted to three thou- sand ! After dinner, Mr. Edmonds, the Chairman, first gave " The King and the People ;" and then "The Members," with an appropriate speech.

Mr. Scholefield, in returning thanks, dwelt with strong disapproba- tion on the proceedings of last session in regard to the Poor-law Bill.

To his dying hour, it would be a satisfaction to him to know that he had opposed it ; and would also be a satisfaction to his children after his death to know, that the name of their father could not be pointed out in the majorities which carried that bill. It was impossible to look at that law without abhorrence. It was a law which went to deprive tlie poor of their most sacred and inalienable risins. WaS it not a fact, that men of the strictest morals, the most industrious and provident habits, were daily thrown out of employment. from various causes over which they could have no control? Was it not a fact, that some of the most deserving characters in the community were daily reduced to penury ? Was it not a fact, that the object of the Poor-laws Bill was to prevent such persons from receiving that support and relief in their affliction to which they were entitled according to all laws human and divine ? As to the clause re- lating to bastardy, he should say but little: it was an un English clause. The mind of Englishmen revolted at it. and justly so; for base indeed would be the man who would wish to throw the whole of the burden upon the woman. It had been said that the law of Elizabeth had given the poor greater claims than those possessed by the poor of any other country. He admitted it • but in place of viewing it as an argument against the law, he always viewed the privileges which it extended as being in favour of it, and calculated to reflect the greatest credit upon the country. The man who had devoted his strength to the good of the community ought, in time of inability to labogr, to be relieved by those who derived the benefit from his early exertions. lie ought to be able to demand assistance as a right, and not to beg it as an alms. It was also said by those who advocated the bill, that ruin threatened the landlords ; and hence was argued the necessity of destroying the poor. He had consideration for the landlords ; but he had also consideration for the great mass of the people of England. It was the duty of the Legislature to protect the whole as well as the landlords. It was the Divine law. that the poor should not perish ; but it was now made the law of England that they should perish,—although those who had so enacted could not find it in their hearts to remove the rich paupers from the Pension-list, upon which they had been living luxuriously for years. It was clear why they did not interfere with the Pension-list : their own families were living upon it, and hence it could not be touched. Why, lie would ask, did they not put on a property.tax? Why not make the rich pay for the support of the poor? Was it not better that the rich should pay, who could afford to pay, rather than the poor should famish ?

Mr. Scholefield was repeatedly cheered during his speech.

Mr. Attwood then addressed the meeting ; and entered at length into a discussion of the Parliamentary proceedings, and his own conduct.

" I think (he said) I do no more than justice to you, as men of Birmingham, when I say that you were mainly instrumental in creating the general demand for Reform among the people of England ; and when that Reform was endangered, it was you that placed yourselves at the head of the public mind, and, speaking the voice of the nation. commanded its success. I will not congratulate you too much on the Bill of Reform thus obtained. because I know tt has disappointed your expectations and mine. It has given us a House of Commons but little better, I am sorry to acknowledge, than the old concern. Some few good men, it is most true, there are in Parliament; but it is with deep and bitter regret that I acknowledge that the majorities have generally been as servile and selfish as in former Houses. When I entered Parliament, I expected to meet bands of patriots animated with the same interests as the people, feeling for their wrongs and oppressions, and determined to redress and relieve them. I almost re- petted that 1 had had a hand in the Reform, when I saw troops of sycophants and time.servers who seemed only anxious to regard their own selfish interests, and to de- stroy the very system of liberty and Reform from which they themselves had drawn their existence. These gentlemen, you may well believe, were not very partial to me: i they looked upon me n some light as a cow looks upon another cow's calf—as a stranger out of my place—a mere Birmingham tradesman, very disagreeable in their eyes. You must not be surprised that 1 received this kind of treatment. The House of Commons is divided into two great parties, the Whig and the Tory. To the former I bad been mainly instrumental in assisting to do a favour too great for proud men ever to forgive ; and to the latter I had been instrumental in assisting to do an injury which interested men could never forgive. This treatment, howeve-, had uo effect upon me. I was obnoxious to them as a tradesman ; I was obnoxious to them as a forward leader in political matters ; and, above all things, I was obnoxious to both parties as having for twenty years denounced and exposed the frightful errors and crimes which they were committing."

He alluded to the recent Ministerial changes— " The Cabinet has been lately much improved; such men as Mr. Ellice, Mr. Spring Rice, Sir John Ilobhouse, Lord Duncannon. and Mr. Abercromby, are very diflirent men from Stanley and Graham. They have never forfeited any pledges to the People —they understand the situation of the People—they have every interest and every in- ducement to excite them to do justice to the People. I entertain, therefore, great hopes that a better day is about to dawn upon our country."

Mr. Attwood, it appears from the following passage, contemplates an early retirement-

" I must now close, with a few words respecting myself. You all know that I entered Parliament with reluctance. I had studied the situation of the country for twenty years ; I had foreseen and foretold every fluctuation of national adversity or prosperity which had occurred during that period ; and I thought it my duty to obey your orders, and render you every possible assistance in my power. I have obeyed your orders, and done every thing in my power, without fear or affection, favour or reward, during two years. I have incessantly dinned the truth into the ears of the House of Commons ; and in my conscience I believe that three-fourths of that House, if the truth could be knovrwentertain opinions very nearly analogous to my own upon the great question of the national prosperity and adversity. In the meanwhile, I have incurred much espouse and much injury from the loss of time ; and I think I should do wrong if I did not in- form you, that I entertain serious thoughts of resigning the situatiou which I hold. (Load cries of" 21'o, aol") You must look out, theretbro, for a stork or a wolf one of these days: and I sincerely wish vou may mimed in nailing a real Representative of the People, more efficient than 1 h'ave been."

One of the toasts had reference to the state of Poland. It called up General Umiuiski ; who briefly spoke his thanks in French.

Whatever the good people at Inverness may think of the Chancel- lor's declaration that too much was done in the last session of Parlia- ment, and that less will probably be done in the next, there are consti- tuencies in the Southern parts of the island who consider it in the light of a downright insult. In Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, and the neighbouring districts, where the Reformers are not noisy, but determined, we learn that a most decided feeling of anger and disap- pointment prevails at the stultification of the Reform Bill, which the Do-as-little-as-possible gentlemen recommend. Ministers may rely upon it, that the resolution to reap substantial benefits from Reform has taken deep root in the land. The Monmouthshire Merlin of Saturday last mentions, that Mr. Hall, Member for the Monmouthshire Bo- roughs, had voluntarily attended a large meeting of his constituents on the previous evening, at which he entered into a detailed account of his Parliamentary conduct. His votes were generally indicative of " impatience" of abuses, and dislike of the truckling, tricky system of conciliation ; and although on that account they must have been ex- ceedingly unpleasant to certain members of the Cabinet and the Conserva- tive party, they seem to have given great satisfaction to his constituents. A requisition was presented to Mr. Hume, who was in theneighbourhood, to attend the meeting of Mr. Hall, with the Monmouth electors ; but that gentleman declined the invitation, on the plea of recent indisposition, and the necessity of relaxtion from business. A meeting was also called at Hereford, at which Mr. Hume's attendance was desired ; but the same cause induced him to procure its postponement. All this is symptomatic of a state of feeling, which will, we doubt not, become very general, and which will render perseverance in a timid and waver- ing course rather difficult and hazardous to the Obstructives of all parties and descriptions.

An address from the inhabitants of Whitby to the Earl of Mulgrave, was presented on the 12th, at the Magistrates' Office in that town. His Lordship, who was accompanied by Lord Morpeth, spoke at length in reply ; referring to his past political conduct, and expressing his full con- viction that his colleagues in the Ministry were prepared to persevere in their resolution to improve the institutions of the country.

Previous page

Previous page