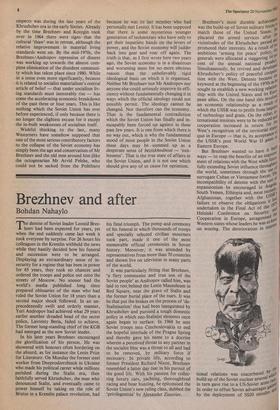

Brezhnev and after

Bohdan Nahaylo

The demise of Soviet leader Leonid Brez- hnev had been expected for years, yet when the end suddenly came last week it took everyone by surprise. For 26 hours his colleagues in the Kremlin withheld the news while they hastily decided how his funeral and succession were to be arranged. Displaying an extraordinary sense of in- security for a regime that has been in power for 65 years, they took no chances and ordered the troops and police out onto the streets of Moscow. No sooner had the world's media published long since prepared obituaries of the man who had ruled the Soviet Union for 18 years than a second major shock followed. In an un- precedentedly swift and orderly manner, Yuri Andropov had achieved what 29 years earlier another dreaded head of the secret police, Lavrenty Beria, failed to achieve. The former long-standing chief of the KGB had emerged as the new Soviet leader.

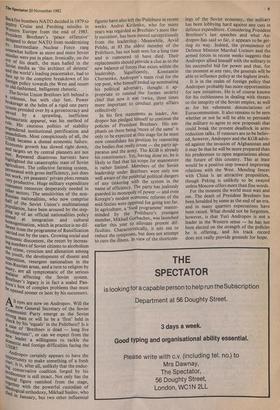

In his later years Brezhnev encouraged the glorification of his person. He was showered with honours often bordering on the absurd, as for instance the Lenin Prize for Literature. On Monday the former steel worker from Dneprodzerzhinsk in Ukraine who made his political career while millions perished during the Stalin era, then faithfully served Khrushchev, the man who denounced Stalin, and eventually came to power himself by taking on the role of Brutus in a Kremlin palace revolution, had

his final triumph. The pomp and ceremony of his funeral in which thousands of troops and specially selected civilian mourners took part, made it one of the most memorable official ceremonies in Soviet history. Moreover, it was attended by representatives from more than 70 countries and shown live on television in many parts of the world.

It was particularly fitting that Brezhnev, `a fiery communist and true son of the Soviet people' as Andropov called him, was laid to rest, behind the Lenin Mausoleum in Red Square, near the grave of Stalin and the former burial place of the tsars. It was he that put the brakes on the process of 'de- Stalinisation' that had been inaugurated by Khrushchev and pursued a tough domestic policy in which neo-Stalinist elements once again began to surface. In 1968 he sent Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia to end the hopeful interlude of the Prague Spring and thereby gave his name to a docrine wherein a perceived threat to any partner in the socialist bloc was a threat to all and had to be removed, by military force if necessary. In private life, according to former President Richard Nixon, Brezhnev resembled a latter day tsar in his pursuit of the good life. With his passion for collec- ting luxury cars, yachting, thoroughbred racing and boar hunting, he epitomised the Soviet Union's new ruling class, dubbed the 'privilegentsia' by Alexander Zinoviev.

The Spectator 20 November 1982 Brezhnev's most durable achieverneri,,I was the build-up of Soviet military forces t'e match those of the United States. he placated the armed services after OA vicissitudes of the Khrushchev period h. promoted their interests. As a result of his ambitious 'arming for peace' policy, tlir generals were allocated a staggering 14 Pe, cent of the annual national Poch/,, L. Simultaneously, he revived and developed Khrushchev's policy of peaceful cooper!; tion with the West. Detente became the keyword at the beginning of the 1970s as sought to establish a new working relation ship with the United States and its fwecro pean allies. On the one hand this involv„f an economic relationship as a result which the USSR was to profit from in of technology and grain. On the other, I'd' ternational tensions were to be reducedanhe cooperation increased in return for the West's recognition of the territorial sta'f quo in Europe — that is, its acceptance the USSR's post World War II gains 1"

Eastern Europe. hoth

But Brezhnev wanted to have it e. ways — to reap the benefits of an irriPr°v ment of relations with the West while for',e, fully extending Soviet influence througOouf the world, sometimes through the use surrogate Cuban or Vietnamese forces. of incompatibility of detente with the sort expansionism he encouraged in Ang°6, South Yemen, Ethiopia and, most recery; Afghanistan, together with the OSoci failure to observe the obligations it 11975 undertaken in the Final Act of the 1 ci Helsinki Conference on Security °Env Cooperation in Europe, antagonised Western states whose leaders he was so lc'3, on wooing. The deterioration in intern by tional relations was exacerbated hich build up of the Soviet nuclear arsenal in turn gave rise to a US-Soviet arms r.061 In order to offset Soviet advantages gjonci by the deployment of SS20 missiles Backfire bombers NATO decided in 1979 to deploy Y Cruise and Pershing missiles in Western Europe from the end of 1983; President Brezhnev's 'peace offensive designed to deter NATO from modernising Its Intermediate Nuclear Force rang somewhat hollow as more and more Soviet Missiles were put in place. Ironically, on the eve of his death, the man hailed in the Soviet media as 'the architect of detente' and the world's leading peacemaker, had to fraee. up to the complete breakdown of his fore' Policy towards the West and resort to old-fashioned, belligerent rhetoric.

The Soviet Union Brezhnev left behind is

ba colossus, but with clay feet. Power yokerage at the helm of a rigid one party stern presided over by a gerontocracy and terved by a sprawling, inefficient bureaucratic apparat, was his method of ride. His cautious politics of stability engendered institutional petrification and Itnmobilism. Most conspiciously of all, the Economicame a dismal economic failure. growth has slowed right down, and targets set by central planners are not !net. . Repeated disastrous harvests have nigh lighted the catastrophic state of Soviet agriculture. The collective farming system, Derrneated with gross inefficiency, just does Vr,lint work, yet peasants' private plots remain erY productive. Huge military expenditure consumes resources desperately needed in o_theru sectors. The sensitivities of the non- hKssiao nationalities, who now comprise alf of the Soviet Union's multinational Do. Pulation, have been aroused by the step- 1314 131) of an official nationalities policy ittlecl at integration and cultural homogenisation, which in practice is no dif- ferent from the programme of Russification carried out by the tsars. Growing social and (rhentiomic discontent, the resort by increas- ing numbers of Soviet citizens to alcoholism th d crime, cynicism and alienation among 0 he Youth, the development of dissent and ?Position, resurgent nationalism in the '12n-Russian areas, and a turn to religion by .1anY, are all symptomatic of the serious ;Li alaise affecting the Soviet system. rezhnev's legacy is in fact a sealed Pan- dora's box of complex problems that must oPened sooner or later by his successors. All eyes are now on Andropov. Will the cr,_ new General Secretary of the Soviet sti7uniunist Party emerge as the Soviet cii,s°n,g man or will he be a 'first' held in a -"( by his 'equals' in the Politburo? Is it g,.ease of 'Brezhnev is dead — long live ti'ezhnevism!', or can we expect from the Uoy' leader a willingness to tackle the SS1,,,illestie and foreign difficulties facing the SR? 0„An, dropov certainly appears to have the stZortunity to make something of a fresh in7con : • It is, after all, unlikely that the endur- 6 servative coalition forged by his c'lledecessor is still intact. Not only has the tocn.tr."1 figure vanished from the stage, ici.„8`;ner with the powerful custodian of tit2legical orthodoxy, Mikhail Suslov, who in January, but two other influential

figures have also left the Politburo in recent weeks. Andrei Kirilenko, who for many years was regarded as Brezhnev's most like- ly successor, has been ousted surreptitiously from the leadership. Meanwhile, Arvid Pelshe, at 83 the oldest member of the Politburo, has not been seen for a long time and is rumoured to have died. Their replacements should provide a clue as to the new balance of forces that exists within the

leadership. Significantly, Konstantin Chernenko, Andropov's main rival for the top post, who himself ended up nominating his political adversary, thought it ap- propriate to remind the former security chief that now it was 'twice, three times more important to conduct party affairs

collectively'.

In his first statements as leader, An- dropov has pledged himself to continue the policies of President Brezhnev. His em- phasis on there being 'more of the same' is only to be expected at this stage for he must now consolidate his position by reassuring the bodies that really count — the party ap- paratus and the army. The KGB is already his constituency. Yet, having done so, he is likely to find that his scope for manoeuvre is rather limited. Members of the Soviet leadership under Brezhnev were only too well aware of the potential political dangers of any tinkering with the system in the name of efficiency. The party has jealously guarded its monopoly of power — and even Kosygin's modest economic reforms of the mid-Sixties were opposed for going too far. In agriculture, a 'food programme' master- minded by the Politburo's youngest member, Mikhail Gorbachev, was launched earlier this year to alleviate present dif- ficulties. Characteristically, it sets out to reduce the symptoms, but does not attempt to cure the illness. In view of the shortcom-

ings of the Soviet economy, the military has been lobbying hard against any cuts in defence expenditure. Considering President Brezhnev's last speeches and what An- dropov has said so far, it appears to be get- ting its way. Indeed, the prominence of Defence Minister Marshal Ustinov and the armed forces in recent weeks suggests that Andropov allied himself with the military in his successful bid for power and that, for the moment at any rate, the generals will be able to influence policy at the highest levels.

It is in the realm of foreign policy that Andropov probably has more opportunities for new initiatives. He is of course known for his ruthlessness in dealing with threats to the integrity of the Soviet empire, as well as for his vehement denunciations of Eurocommunism. It also remains to be seen whether or not he will be able to persuade the military to agree to new proposals that could break the present deadlock in arms reduction talks. If rumours are to be believ- ed, however, Andropov and the KGB advis- ed against the invasion of Afghanistan and it may be that he will be more prepared than his predecessor to open negotiations about the future of this country. This at least would be a positive step toward improving relations with the West. Mending fences with China is an attractive proposition, though Peking is unlikely to be swayed unless Moscow offers more than fine words.

For the moment the world must wait and see. The death of President Brezhnev has been heralded by some as the end of an era, and in many quarters expectations have been raised. What should not be forgotten, however, is that Yuri Andropov is not a leader in the Western sense — he has not been elected on the strength of the policies he is offering, and his track record does not really provide grounds for hope.

Previous page

Previous page