Stan Hugill, shantyman

Roy Kerridge

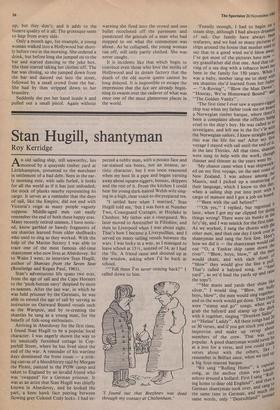

An old sailing ship, still seaworthy, lies An by a quayside timber yard at Littlehampton, presented to the merchant in settlement of a bad debt. Seen in the ear- ly morning mist, with sails furled, it looks for all the world as if it has just unloaded, the stock of planks nearby representing its cargo. It serves as a reminder that the days of sail, like the Empire, did not end with Victoria's reign as many people vaguely suppose. Middle-aged men can easily remember the end of both these happy eras. Many recently retired seamen, I have notic- ed, know garbled or bawdy fragments of sea shanties learned from older shellbacks who used to sing as they worked. With the help of the Marine Society I was able to trace one of the most famous old-time shantymen who now lives at Aberdovey. So to Wales I went, to interview Stan Hugill, author of Shanties from the Seven Seas (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1961).

Stan's adventurous life spans two eras, from the age of sail and the Cape Homers to the 'push-button navy' despised by most ex-seamen. After the last war, in which he was held prisoner by the Germans, he was able to extend the age of sail by serving as instructor on Outward Bound vessels such as the Warspite, and by re-creating the shanties he sang as a young man, for the benefit of folk-song enthusiasts.

Arriving in Aberdovey for the first time, I found Stan Hugill to be a popular local character. I was eagerly shown the way to his nautically furnished cottage in Cop- perhill Street, where he has lived since the end of the war. A reminder of his wartime days dominated the front room — a strik- ing canvas of a bloodthirsty raid by Morgan the Pirate, painted in the POW camp and taken to England by an invalid friend who was 'swapped' for a German prisoner. It was as an artist that Stan Hugill was chiefly known in Aberdovey, and he looked the part, a keen hawk face peering between flowing grey Colonel Cody locks. I had ex-

pected a tubby man, with a potato face and tar-stained sea boots, not an intense, ar- tistic character, but I was soon reassured when my host lit a pipe and began yarning away about square-riggers, bosuns, skippers and the rest of it. From the kitchen I could hear his young dark-haired Welsh wife sing- ing in a high, clear voice as she prepared tea.

`I settled here when I married,' Stan Hugill told me, 'but I was born at Number Two, Coastguard Cottages, at Hoylake in Cheshire. My father was a coastguard. We later moved to Anstruther in Fifeshire, and then to Liverpool when I was about eight. That's how I became a Liverpudlian, and I served on many sailing vessels between the wars. I was lucky in a way, as I managed to leave school at 131/2, instead of 14, as I had the 'flu. A friend came and shouted up at the window, asking when I'd be back at school.

"'Tell them Pm never coming back!" I called down to him.

`I found out that Brezhnev was dead through my contact at Cheltenham.'

'Funnily enough, I had to begin on a steam ship, although I had always dreamed of sail. Our family have always been seafarers, and we had so many pictures 0' ships around the house that mother used to say that in a good wind we'd blow away I've got most of the pictures here now -- my grandfather did that one. And that car- ving of a sea dog with a tobacco bowl has, been in the family for 150 years. When was a baby, mother sang me to sleep with sea shanties she'd learned from her father — "A-Roving", "Blow the Man Down A' "Hooray, We're Homeward Bound" an "The Golden Vanity". `The first time I ever saw a square-rigged, ship was when my father took me on board a Norwegian timber barque, where thered been a complaint about the officers being cruel to the ship's boy. He was called in t°,, investigate, and left me in the foc's'le with the Norwegian sailors. I knew straight awaY this was the life for me! After my lir voyage I stayed with sail until the end of it, in the late Thirties. All that time, shantie,s. were sung to help with the work, thougn thinner and thinner as the years went by `My chance came when I was shipwreai ed on my first voyage, on the east coast ° New Zealand. I was ashore among thef Maoris, and I picked up a smattering °' their language, which I know to this day' when a sailing ship put into port IA'ith,3 cargo of manure and I got a job on board'

"'Been with the sail before?"

'"Oh yes," I replied, but regretted it later, when I got my ear clipped for doinge things wrong! There were six bunks in th fo'c'sle, and I was seasick for the first tinle As we worked, I sang the chorus with the other men, and then one day I took over ,, shantyman and sang the first line. Here 1 how we did it — the shantyman would efe out "0, a Yankee ship came down the river". "Blow, boys, blow," all the mei. would chant, and with each shout on "blow" they would give the line a P11,,i That's called a halyard song, or 11_,a; yard", as we'd haul the yards up and raise

the tops'l. like

"'Her masts and yards they shine silver," I would sing. "Blow, me WY boys, blow", the men would sing toget,n and so the work would get done. Then t"'",d were "stamp and go" songs, when we 1, grab the halyard and stamp up the deco0 owrit,h,HitietioagnethLeard,dsyingiAngli`t`hDersuensokenngsShaiald° or 30 verses, and if you got stuck you about improvise and make up verses members of the crew. That was very popular. A good shantyman would never at a loss for a verse, and you could trael verses about with the others, like remember in Belfast once, when we tied ur a big four-masted barque. `We sang "Rolling Home", a e._a'-„leci song, as the anchor chain was na".0, ashore around a bollard. First I sang "gu_ „ German n egr mhome s hto a ndteyamr aold t oEngland", a and and s anthe gt:hte

the same tune in German, and m instead same words, only "Deutschland"

of "England". That took an hour to do, singing all the time, back in 1928.' Listening to Stan Hugill, I gained the im- Pression that on the ships of his day men of efv.erY race and nationality could mingle in wriendship and learn from one another. He I as. of the opinion that shanties were 'an rish-Negro mixture'. If so, they share an caneestrY with jazz, blues, rock-and-roll and w°11ntrY-and-western music, yet as they n ere songs of work, not play, they could Nic/t be transformed into jukebox tunes. egro worksongs, with 'call and response' Patte Irishrns , suggest an obvious parallel and navvies sang old songs in unison as road Pickaxes flew on many an English "ad until the late 1960s. N:Some of the songs had a touch of the e r `gro spiritual about them,' Stan Hugill called, and sang: 'Oh, a drop of Nelson's blood wouldn't ,..do us any harm,

roll the old chariot along.'

nut icon's blood" meant rum,' he added, si ifie don't know what the "old chariot" One of my main teachers was a cli6 negro from Barbados, by name of Har- heng. Harding the Barbadian Barbarian" hit called himself, and he taught me "the 80e1"iliFs". That's when you make your voice Igh and wobble the words, drawing tNheoln out like this — "Too lay ay, o-o-o". lilt , Yodelling, but with a similar falsetto demonstrated by singing several shan-

ties in a style reminiscent of Hank Williams and other hillbilly singers. `On deepwater ships we sang "Whisky Johnny", "Blow the Man Down" and "Reuben Ranzo". That's a good song. "Ranzo, boy, Ranzo!" He was supposed to have been a Bond Street tailor, who got shanghaied on board a whaler. See my melodeons there on the wall? We called the melodeon the "North Sea Piano". Of course you couldn't play any instruments with shanties, as they were songs to work td, but afterwards we'd have some good old sing-songs just for pleasure, often putting English words to foreign ditties we'd picked up, and playing melodeons, comb and paper, if we couldn't get a mouth organ, and all kinds of instruments we'd make ourselves. The West African sailors were best at this: they'd get a pig's bladder and stretch it over a paint tin for a drum, or use elastic bands as guitar strings. "Fore- bitters", we'd call these songs, and the instruments were called a "fufu band".' (As far as my landlubberly memory serves me, 'forebitter' refers to the bitts the sailors sat on, which are rather like bollards on the fore of the ship. Tau' may derive from the West African spicy dish of that name. At least that was my suggestion, and Stan didn't contradict me.) Stan Hugill had to move on to steam vessels in the end, and his career as a work- ing shantyman was over. His brother, who was not a seaman but had a keen ear for music and played fiddle, piano and man- dolin, took down words and music from Stan's singing and helped him write his book. Stan Hugill's second career as an entertainer at folk clubs was born, and he became a legendary figure among young en- thusiasts. Eventually the rise of comprehen- sive schools brought the grammar and art school based folk cult to its present decline. Now Stan is in demand at American Festivals of Sail, and crosses the Atlantic by air to re-enact his shantyman past on replicas of 19th-century clippers afloat in New England harbours, among crowds in period dress.

`Can you imagine anyone in England putting on a show on that scale?' he demanded, and I had to admit that I couldn't. 'Of course the folk clubs have been good to me, there's no denying that. With their use gone, the shanties are just museum pieces now. The folklorists have all kinds of controversies. Some of them insist that concertinas were played on board ship all the time, and take no notice when I deny this, although I was there and they weren't. Then again, some of them say the songs should all be in a minor key, whereas the sailors sang in a major.'

I know nothing of keys, so he demonstrated, and the major key sounded like a working man roaring lustily above a gale, while the minor sounded like a very pretentious folk singer. `People nowadays imagine that cowboys rounded up the cattle holding guitars,' I mentioned, but he rather scoffed at cowboys, despite his leonine Buffalo Bill appearance.

`The heyday of the open range only lasted ten years, as against hundreds of years of sail,' he pointed out. 'By the 1880s the Wild West shows had begun — the beginning of the end. It's like folk clubs what was once real becomes enter- tainment.'

`Did your son go to sea?' I inquired.

'No, the tradition has ended. I advised him against it, as the true seafaring life is over. It's all gadgets now, and tankers with mile-long decks and the sailors riding up and down them on tricycles — can you im- agine? No, my boy lives in Southampton, where he's doing well as a borough surveyor. Britain isn't a seafaring nation any more, you must face the facts.'

Any trace of bitterness in my host's voice was dispelled when Mrs Hugill returned bearing cups of tea and a strawberry gateau.

`I remember the Earthpool, a big square rigger,' he said dreamily, as he filled his pipe. 'In 1929 that was, and we sang our version of "Fire Down Below" as we work- ed the pumps. "She was just a village maid..."' His lilting voice seemed to follow me as I walked down to the shore. A line of yellow sand was lit up by the evening sun. Aber- dovey reminded me of Teignmouth in Devon, another rather 1930-ish resort where happy families ride along the coast by train, admiring shelducks, curlews, oystercatchers and herons from the shoreside windows.

In the National Park Centre I found pic- tures of ships long broken up, of the kind Stan Hugill once sailed in. Nearby was the Mid-Wales Tourism Centre, with its foot- path and Adventure Base. When Adven- ture, that marvellous word, becomes an organised part of the tourist industry, just another service provided by the all-caring Welfare State and its patient ratepayers, then, with Stan Hugill, we can sing 'Good- bye, fare ye well' to the days of wooden ships and iron men.

Previous page

Previous page