The proud walker

Christopher Bray

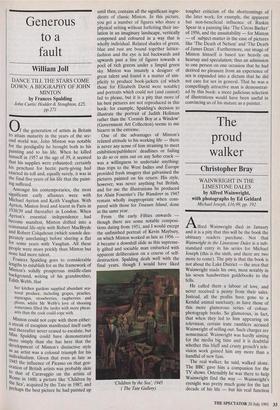

WAINWRIGHT IN THE LIMESTONE DALES by Alfred Wainwright, with photographs by Ed Geldard Michael Joseph, £16.99, pp. 192 Alfred Wainwright died in January and it is a pity that this will be the book the obituary readers purchase. Not that Wainwright in the Limestone Dales is a sub- standard entry in his series for Michael Joseph (this is the sixth, and there are two more to come). The pity is that the book is not about the Lake District — the area that Wainwright made his own, most notably in his seven handwritten guidebooks to the fells.

He called them a labour of love, and never received a penny from their sales. Instead, all the profits have gone to a Kendal animal sanctuary, as have those of this more glamorous series of colour- photograph books. So glamorous, in fact, that when they led to him appearing on television, certain irate ramblers accused Wainwright of selling out. Such charges are nonsensical. Wainwright was hardly aiming for the media big time and it is doubtful whether this bluff and crusty grouch's tele- vision work gained him any more than a handful of new fans.

The real walker, he said, walked alone. The BBC gave him a companion for the TV shows. Ostensibly he was there to help Wainwright find the way — Wainwright's eyesight was pretty much gone for the last decade of his life — but his real function was to blether on during Wainwright's dis- comfiting (to television) silence. For Wain- wright words were too precious to be expended on the self-evident. Statements like 'there's a bit of cloud coming in from the east' were left to the other chap.

Taciturn he might have been, but Wain- wright could write. Unfortunately, the pre- sent book has been sub-edited into supposed shape, Wainwright's prose was sometimes too lush to be evocative but it was always precise — often a more affect- ing characteristic. Thanks to Wordsworth and Coleridge we are wont to associate the Lake District with Romanticism, yet if Wainwright produced some of the best Lakeland literature, then he did so in classical terms. He had the classicist's love of system, a quality he found abundantly on display in maps. He enjoyed looking at them (`far better than a book'), but he loved making them. In his memoirs he reproduced maps of Africa and India drawn during his schooldays. They are astonishingly suggestive of the work to come. All he needed was a motif, and he found it at the age of 23, gazing down on Lake Windermere from Orrest Head. What did he see? A means, one suspects, of ordering chaos. He liked the way the high vantage point allowed him to observe the mountain system fitting together. In fact, he liked it so much that he wished Fairfield — a monster of a mountain just shy of 3,000 feet — was 1,000 feet higher. (Small beer to a man who advocated ascending the near-vertical Wansfell Pike before breakfast!) Wainwright's drawings have always done less for me than his prose and his maps. Nonetheless, there is a case for saying that a photograph of Helvellyn, say, could never be as memorably pregnant as one of his illustrations. Photographs depend on atmo- sphere for their impact, but even granted fine weather — a rarity in Lakeland good shots are possible only for a couple of hours at either end of the day. Getting all the photographs for one of these books technically and aesthetically satisfying would take more than a lifetime. Ed Gel- dard is clearly not without talent, but his brief is too big. Derry Brabbs, who shot the earlier books in the series, was similarly luckless. The moody evanescence of black and white would have made things easier — a colour shot of bad weather is always dull, not so with monochrome — but doubtless sales would have been affected.

Of Scafell Wainwright wrote:

A man may stand. . . beneath the precipice.. . often, tormented by writhing mists, and, as in a great cathedral, lose all his conceit.

His humility in the face of nature might seem archaic. Certainly it was evidence of a man who only uneasily lived in the 20th century. But because he did not fit in, he felt no need to pander to a market. Instead, the market came to him.

Previous page

Previous page